Copyright as a means of special protection for the written product of an author has a long history, dating back to the guilds of antiquity. Our own laws regarding copyright stem from British jurisprudence, which in 1710 granted to authors the first meaningful protection of their own works.

In America, the framers of the Constitution declared that “The Congress shall have power to… promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”[2] Note what has come about as a legal result of this provision:

- Copyright is not an inherent right of an author, editor, composer, printer or publisher; it is a privilege specifically granted to certain works by an act of Congress for a limited time.

- Certain items such as government documents, book or song titles, or tabulated lists specifically have been legislatively excluded from copyright protection by Congress.

- Once the limited term of a copyright has expired, a work will enter the public domain and become free for use by all. Anything no longer protected by statute is deemed to be in the “public domain,” as well as any works which are specifically donated to the public domain.

The law secures the exclusive right to control one’s own creative contribution only “for limited times.” Material protectable by copyright includes original works of authorship, translations of a work from one language to another, and “derivative” works taken or compiled from existing sources. Add to this the entire realm of musical composition and artistic endeavor, and one can see the scope of what is copyrightable.

The duration of copyright protection has varied over the years. The first copyright legislation enacted in this country granted a 14-year term, renewable for an identical period. In 1909 a new copyright law fixed the initial period at 28 years, with an equal renewal period. The copyright law of 1978 as amended has increased the maximum from 56 years to the life of the author plus 50 years (with certain mandated exceptions). Congress is currently considering legislation to extend the term of copyright by an additional 20 years, even though further extension will likely benefit only the copyright-holding publishers rather than the original authors or their immediate heirs.

Under the 1909 law, any work published before 1940 would now be in the public domain. However, under the current law, works published between 1922 and 1940 will not enter the public domain until the period 1997-2015. Only works published and copyrighted before 1922 are currently in the public domain. The change in the 1978 law has led to many abuses and much windfall profiteering which does not benefit in any way the original authors or their heirs.

For example, the Manual Grammar of the Greek NT by Dana and Mantey was completed in 1935, and under the 1909 law would have become part of the public domain as of 1991. From that point, low-cost reprint houses such as CBD/Hendrickson then could have produced royalty-free copies selling for approximately $15. However, under the 1978 law, Macmillan publishers retain the copyright to Dana and Mantey until the year 2010, thus reaping windfall profits beyond what they had ever anticipated due to the unexpected extension of copyright. In the meantime Macmillan has increased the price of that small volume from what was already an expensive $39 in 1992 to an outrageous $57 today.

The current copyright law adversely impacts the common good by extending a reasonable 56-year period of protection solely to enhance the profitability of a few older books which continue to sell. The greater benefit of public access to quality material of the past has been stifled by publishers’ lobbyists who have transformed the copyright law into a profiteering tool which frustrates the public good.

Yet in terms of the present paper, it is not the term length of copyright protection which is the matter of primary concern. My interest is in the matter of copyright in regard to ancient religious texts which de facto should be in the public domain, especially in regard to any religious work which its advocates claim to have been derived from direct revelation and inspiration such as the Bible. In this paper, my concern clearly transcends the legal aspects of copyright law and contemplates the moral implication of copyright as applied to such texts. There are two issues at stake: the original language texts of Scripture, and the translations of what is deemed to be Holy Scripture into modern languages. Although the same concerns could apply to the sacred texts of any religion, I intend to speak from within an evangelical Christian context respecting those matters which directly concern our community of faith, and which reflect the believers’ devotion to those sacred texts.

(1) Ancient Biblical Texts

The OT in Hebrew/Aramaic and the NT in Greek have always been received by the Christian community as the revealed and inspired word of God. The revelation of these texts occurred centuries ago, and they have been vouchsafed to us in thousands of original-language manuscripts, ancient language translations, and patristic quotations. The science of textual criticism has labored long and hard to ensure that the printed editions of the Greek and Hebrew texts we currently enjoy are substantially identical to the text originally revealed by God and inscribed by the human authors. So much labor and effort has been devoted to the restoration of the sacred autograph that in most cases we are 100% certain as to the original reading of the text, and even where differences of reading occur we are quite certain that the true reading is preserved among the MSS we currently possess.

It might seem inconceivable that any modern printed edition of these ancient sacred scriptures would ever impose a claim to copyright since the public domain nature of these ancient texts should be plain by virtue of age. Yet the Bible Societies and other publishers since the end of the last century have presumed to copyright every “critically-edited” original language text that they have published, and even take the position that the text as edited even though claimed to be the closest possible reproduction of the autographs originally given by inspiration of God is the specific “intellectual property” of the Bible Societies themselves."[3]

Note that this writer does not object to the copyright of introductions, appendices, the forms of an apparatus, or other explanatory details, but the biblical text itself should be a different matter. Certainly the vast labor of learned editors in collating MSS, comparing and evaluating the variations, and publishing the text determined by such scholarly effort is valuable for the Christian community as a whole, but the question is whether such labor should be restricted by copyright from its free and open use by God’s people. Should a book devoted to textual restoration be published, such a work clearly would be copyrightable. For example, Bruce Metzger has written a volume explaining the reasons for the decisions of the UBS committee in over 1400 places of textual variance.[4] That volume clearly reflects original creative work and is deservedly protectable by copyright.

The biblical text itself is a different matter, however. The facts are plain: over 90% of the biblical text is common in all editions, regardless of text type, whether printed in the present century or in the 1500s. Further, almost every variant reading cited in modern critical editions was known and published over a century ago, and scholars have been free to select from among a mass of variants since the time of Mill in 1707. All these variant readings are as much a part of the public domain as the Greek text itself, regardless of their individual selection or rejection by modern critical editors.

The present writer compared the entire Greek text of the 1994 Nestle 27th edition against the (now) public domain 1881 Westcott-Hort Greek text. Out of approximately 138,000 words, there were only about 1600 variational differences between both editions, and half of these were merely the presence or absence of brackets surrounding identical text. Most of the remaining 800 differences were already clearly known from previously published editions, critical apparati or collations of the past century, which shows clearly that in textual matters, as elsewhere, “there is nothing new under the sun.”

It is interesting to note that the editors of the UBS/Nestle 27 text made at least one alteration from the text of Westcott and Hort in every book of the NT, seemingly thus to ensure that their edition would not be identical with the public domain Westcott-Hort text in any given NT book. By rearranging variant readings, they produced a text differing only sporadically from that of Westcott and Hort. That resultant text — which remains 99.9% identical to its public domain predecessor — is then somehow claimed to be unique, the result of contemporary scholarly labor, and thus copyrightable.

A similar procedure is followed in regard to the Bible Societies’ Stuttgart edition of the Hebrew/Aramaic Old Testament, which merely reproduces the exact text of the ancient manuscript St. Petersburg (Leningrad) B19A, whose text remains virtually identical to almost all other MSS and previous printed editions of the Hebrew Bible. Even where slight differences occur in MS B19A which reflect scribal peculiarities or differences between recensions, virtually all of the basic variations had long ago been noted in the collation data of Kennicott and Rossi from the 1700s. Again, there is “nothing new under the sun” — and that which is not new should not be copyrightable.

Some might ask, however, is not the deep and diligent labor of the critic sufficient in itself to merit copyright protection? The answer is “no”; Supreme Court decisions such as Rural Telephone Feist[5] have declared that what is termed “sweat of the brow” labor, based upon intellectual decisions regarding pre-existing factual data is specifically excluded from copyright protection.[6] Editorial selection from pre-existing public domain readings does not in itself create a protectable entity.[7]

The present writer has prepared a volume, The Greek New Testament according to the Byzantine/Majority Textform.[8] Every reading in that edition, though carefully selected by myself and my co-editor from among numerous variants, was derived from pre-existing public domain sources, and copyright is thus only claimed for the introduction and appendices to that volume. (the Greek text itself was released as public-domain freeware in the Online Bible computer program some four years earlier, and could not be ex post facto copyrighted in any case). Yet how by any criterion a text constructed out of pre-existing ancient manuscript data should be copyrightable seems beyond comprehension, even if that text reflected the result of fifteen years of joint editorial research and evaluation of individual variant readings. But the truth is plain: our labor created nothing new, but merely utilized freely available material from the past in light of a specific text-critical methodology in order to construct a close approximation to the autograph text. “Sweat of the brow” labor of this nature is not copyrightable, regardless of its merit.[9] My co-editor and myself freely offered the electronic form of our text to the public and the publisher with no thought of remuneration or personal gain, specifically because it was the biblical text which was at issue. There is no good reason why the Bible Societies or other publishers should not apply the same policy to the original-language source texts of the Old or New Testaments.

If a work is merely a reflection of a public-domain text or a reproduction of public domain variations from manuscripts which make up that text, copyright should not be claimed. There is no original work being performed, and the creative selection which produces the final product is strictly labor-based.

Scholarly labor in such a situation (which is commendable) merely selects a pattern of readings out of pre-existing data and publishes that pattern as an edition of the Greek or Hebrew Bible.[10] Much labor is involved, and certainly “the laborer is worthy of his hire.” The authors or publishers of such editions will generate the deserved profit from the initial publication of such works. However, the text as an entity should not be copyrightable (though introductions, prolegomena, and the specific format of a critical apparatus are protected). Once the publication of an edited biblical text has occurred, anyone should be able to utilize that edition freely as public domain material, since those texts themselves claim to be nothing more than an almost exact equivalent of the inspired autograph. God Himself was the initial publisher long ago; does He not hold the ultimate copyright to His own divinely-revealed words? Is God’s intent to benefit His people by the free and unhindered dissemination of that word, or not?

The time is long overdue for the Bible Societies to renounce copyright on the original language texts of the Bibles that they prepare and distribute.[11] This especially includes the elimination of the incongruous policy of charging a license fee or royalty payment in order to utilize what they claim are the original texts of the word of God in either printed or electronic form. The Bible Societies were constituted to serve the churches and to be supported by freewill gifts from God’s people. Their charter declares their mission to be a united endeavor based upon cooperation from Christians and churches of various denominations to promote the dissemination of copies and portions of Scripture at the lowest possible cost with the goal of enhancing and not of restricting the distribution of the biblical texts and translations.[12] With the advent of electronic publishing, the lowest possible cost is now often free, except for the intrusion of license or royalty fees. To charge such fees — whether to a consumer, book publisher or software programmer — merely so they might utilize a translation or critically-restored version of the word of God is not only unbiblical (“Freely have you received, freely give”), but borders on the unethical and unconscionable. Yet such fees along with other restrictions continue to be imposed whenever publishers or individuals might desire to use such edited texts to promote the reading, study, and use of the word of God. Copyright claims and licensing fees imposed upon God’s people merely so that they can use God’s Word is an immoral action into which the Bible Societies themselves should be ashamed ever to have entered.

Such a policy does not serve God’s people in the most honorable or efficient manner, and anyone should be ashamed to charge a fee for “permission” to publish God’s holy word. I would exhort the Bible Societies to eliminate all royalty or license fee restrictions and to permit the free dissemination of the biblical texts in the original languages and ancient versions. While it is obviously permissible for a publisher to recoup costs of production and advertising in their own printed volumes, it is quite another matter to claim that the very text of the word of God is some sort of “proprietary matter” or “intellectual property” which can be bartered and sold by those who maintain the exclusive copyright to such. There is a guilt which remains upon certain heads in this regard, and the Bible Societies in particular need once more to recognize their original mission and purpose and begin to support those purposes with integrity and responsibility and not with bullying legal claims or talk of “intellectual property” which supposedly subsists in man’s rendition of God’s holy word.

(2) Modernized Bible Versions

Another area in which the laws of copyright have been invoked to the disadvantage of God’s people involves modernized English renditions of previous English translations. Certainly, translation from one language into another is protected by copyright law. This includes modern translations of any ancient text even though the original language forms of such texts may be in the public domain. Homer’s Odyssey translated into English is clearly protected by copyright; but it is questionable whether putting the works of Shakespeare into contemporary English rather than its seventeenth-century form is really “translation.” A questionable and “thin” use of the translation provision of the copyright law has been manipulated by certain publishers to create an illusion of “translation” when little or no real translation has occurred.

Translation reflects the original creative work of those who render a text from one language to another. The simple modernization of older English words or expressions to those in current use is not translation, nor is the restructuring of antiquated English syntax into that commonly received. Merely because a rendition ultimately derives from a non-English original is not sufficient ground for presupposing that the modernization of the archaic English text is a primary act of “translation,” regardless of whether the original-language texts are consulted and “diligently compared” during the modernization process. For example, no one would claim that the KJV is a “translation” of the Bishop’s Bible, even though a similar process occurred in that revision paralleling what one sees in the NKJV or NASV. There is no “original creation” involved in such a process, and the result should not have been copyrighted, let alone have become proprietary to any individual publisher. Infringement cannot and should not occur when significant creativity has not been involved in the production of a work. This of course does not preclude a publisher from claiming and even filing for copyright protection. The US Copyright Office will supply notice of copyright to almost any work submitted with the proper forms and fees. The Copyright Office does not have the time or manpower to determine the validity of that copyright, but notes that any infringement of copyright must be pursued in a court of law, and only the court can determine whether a claimed copyright is valid. The fact that a work is issued a certificate by the Copyright Office does not a valid copyright make.

Consider a parallel example: were I to prepare and attempt to copyright a novel derived from John Grisham’s The Firm, with 95% of my text still in agreement with Grisham’s original wording (only the names of the characters might be changed), I certainly would not possess a valid copyright, regardless of the action of the US Copyright Office concerning my application for such. In fact, I certainly would be liable for damages due to plagiarizing infringement.

To consider even the previous example of a work which is clearly in the public domain: were I to modernize the 5% Elizabethan English of Shakespeare and leave 95% of the text as he originally wrote it, my copyright on the final product would and should be called into question as a “non- original” work, which basically (though legally) plagiarized the Bard’s original text. Certainly, I could not be sued for appropriating public domain material; but anyone else could modernize Shakespeare in an identical or near-identical fashion so as to produce a text like my own, and I would have no legal recourse, since by definition infringement could not occur.

The slight modification of an original source does not represent a creative production which should be protectable by copyright. It would smack of blatant plagiarism for me to claim “authorship” and copyright and royalty protection for my Shakespearean text where 95% of it remains identical to the original.

The case is no different in regard to so-called English Bible “translations” which are primarily mere modernizations of older public domain versions. The bulk of the text of such modernizing versions is identical to that found in their public domain predecessors, and almost anyone familiar with contemporary English would be able to perform the same task, even without a knowledge of the original languages. Despite claims to that effect, the modernization of archaic language and restructuring its form of expression, even in light of the original underlying texts, is not and should not be considered "translation," nor should be protected by copyright.

Two major translations currently marketed are modernizations of older translations which long ago became part of the public domain in this country. Regardless of the scholarship involved in its production, the New King James Version is little more than the modernization and restructuring of the 1759 Blayney revision of the 1611 KJV. Words and phraseology were updated, but significant “real” translation rarely occurred. The facts are simple: the average person who can handle Elizabethan English not being familiar with the NKJV and not consulting such in the process could randomly select almost any chapter of the original King James and modernize it so successfully that he or she will find that the resultant text will be approximately 95% identical to the NKJV.

Such a revision process primarily concerns simple matters such as the alteration of “thee” or “thou” into “you” or the altering of “God forbid” into “May it not be” or “Certainly not.” Whether one proclaims “Thus saith the LORD” or “Thus says the LORD” the public domain nature of the text remains evident. Even the removal of archaisms (such as replacing “neesing” with “sneezing” or “letteth” with “restrains”) is not “translation,” but simple non-copyrightable modernization.

Such a modernization process also includes basic syntactical restructuring: “Know ye not?” becomes “Know you not?” and must be restructured into “Do you not know?” Again, no real “translation” occurs with such a process, but merely the modernization of older forms of expression within the same language base. Most anyone familiar with older and current English should be able to produce a nearly identical product, even without consulting and comparing against the original Greek and Hebrew/Aramaic underlying texts.[13]

The case is simple: no one should presume to claim copyright protection for simple English modernization, whether the text be that of Shakespeare or the word of God itself. Yet every modernized revision of the KJV claims copyright protection — not only the NKJV, but also minor editions such as Jay Green’s “Modern KJV,” and the recently-advertised “21st Century KJV.” None of these editions reflects a true work of translation, since little or no real “translation” has actually occurred to produce the final product.

The Lockman Foundation similarly claims copyright for their “translation” of the New American Standard Version when it also is little more than a modernization of the public domain American Standard Version of 1901. As an experiment, the present writer modernized a sample chapter of the NT (Matthew 4) from the ASV 1901 without consulting either the NASV or the Greek text. Without even trying, my modern English result was 96% identical with the wording of the NASV. In the 4% where differences of rendering occurred, either my own or the NASV rendering could have been acceptable (I of course was prejudiced in favor of my own rendition). Lest anyone presume that such occurred because I was already familiar with either the NASV or the ASV, this was not the case, since I have not used the NASV during the past ten years, and rarely use the ASV. I also did not consult the underlying Greek text during the modernization process.

The claim is regularly made in promoting both the NKJV and NASV regarding the diligent and strenuous labor of numerous editors and translators of both translations over a period of many years, at great expense, and how stylists went over every line of the product to bring it to perfection. While this is true, and a noble undertaking in all respects, the fact remains that, despite all the hoopla, the end result in either version is a product which in general the average English-speaking person with simple common sense could create on the fly as he or she read from the original KJV or ASV, modernizing the English as need required.

Certainly, those who know the biblical languages can improve the final product at certain points, but for the average person the end result remains similar to what anyone without the benefit of scholarship or ancient language skills could accomplish. The current text of both editions remains primarily a mere “modernization” of pre-existing public domain translations.

By pressing a claim of copyright, both the Lockman Foundation and Thomas Nelson Publishers. suggest that there is something “original,” “creative” and “unique” in their modernized. “translations.” But remember Grisham and Shakespeare: had the identical process been used to make a “modernization” of a currently copyrighted volume, and the respective final texts ever been subjected to an open demonstration of how easily anyone could produce virtually the same product by altering the original English-language sources, I doubt that any judge or jury would hold the text to be copyrightable, let alone proprietary, but that such publishers would be found liable for plagiarism of the copyrighted text. The advantage which the KJV and NASV publishers possess is that, just as with Shakespeare, no one can or will bring charges from the original KJV or ASV in regard to infringement; it seems ludicrous that they should then claim a particular proprietary right in the modernized product merely because no claim of infringement is possible.

Do not misunderstand my point: the problem is not with these publishers and their modern renditions of public domain translations, nor even with their making a reasonable profit from publishing such versions in a variety of forms. The problem is with the specific claim that such texts must become exclusive and proprietary to them, protected by copyright, and requiring a license or royalty fee from anyone who might otherwise desire to publish and distribute such texts.

One publisher who licenses the NASV from the Lockman Foundation told me that they must pay a royalty exceeding 10% to the Lockman Foundation for each copy of the NASV that they sell. This should not be the case, considering that virtually anyone could produce a near-identical product with no expenditure of effort beyond mere English modernization of the 1901 ASV.

Allow me to propose a money-saving alternative for all publishers: assemble a team of scholars, who will work voluntarily for the glory of God alone, who will then use computer technology for search-and-replace, and finally completely modernize the 1901 ASV from scratch, so as to produce totally public domain modern version of the ASV. The result will be a royalty-free Modern American Standard Version (MASV) version which will be 95% or more identical in wording to the NASV, but which will require no licensing or royalty fees for anyone to use. Such a text would clearly be available freely to all, and anyone would be free to publish that Modern ASV with no copyright problems, let alone license or royalty fees. The same can just as easily be done with the KJV so as to produce a free public domain equivalent to the NKJV which would be nearly identical to it. The rationale for such a proposal is clear: the word of God in any form should be free for all to use with no restrictions or hindrances to hobble the free dissemination of God’s holy word to a dying world. License and royalty fees have become attached to the text of the word of God primarily because publishers are more interested in the almighty dollar than they are in a commitment to serving God and ministering to His people.

Note that I am not arguing that publishers should not print and distribute numerous Bible editions; nor that they cannot make some profit on each copy sold. I am rather railing against proprietary restrictions which hinder the free and open dissemination of God’s word — regardless of translation — whether such restrictions are designed to enrich the publishers or not. The KJV itself appears in hundreds of editions from numerous publishers in every type of format, varying in price and quality. The 1901 ASV has also been reprinted by various publishers since it entered the public domain in 1957. The publishers of the KJV or the 1901 ASV make whatever profit they can in a free market economy and serve the people of God in the process. No proprietary claim can be involved with the dissemination of those versions, since they are already a part of the public domain.

It should be recognized that neither the quality of the KJV or ASV nor the profits for their publishers are harmed by the free and open availability of those versions from multiple sources, and God’s people derive great spiritual benefit thereby. Licensing and royalty restrictions imposed upon the modernizations of those versions reflect a bold attempt to seize the rights to God’s word from His people and financially to restrict the free distribution of that word until the proper fee be paid. Publishers should freely release such modernized versions into the public domain so that all the people of God may be unrestricted in their use of such, with no financial or legal hindrances attached.

Every publisher can earn a just profit by marketing the biblical text in a multitude of specialty editions, whether as study Bibles (e.g., African Heritage, Women, Men, Charismatics, Baptists, Wesleyans, the Orthodox or the Reformed). There is no question that introductions, study notes and supplementary materials which appear in such editions will remain proprietary and protected by copyright. The only issue is that the text of Scripture itself should be freely distributable, regardless of translation. Modernized versions of public domain translations should not become the peculiar property of any publisher, regardless of sponsorship, how many revisers participated, or at what cost — the ultimate product of “sweat of the brow” labor should not be copyrightable. Real translation — a re-casting of the biblical text into a wholly unique form of expression directly from the original languages — has not occurred in such cases, only the modernization of an existing freely available text.

(3) Other Modern Translations

But what about translations which are not mere modernizations? According to law, these indeed can be copyrighted and thus licensed to various publishers and distributors for a fee. Most modern dynamic equivalency translations fall under this category, whether the New International Version, the Jerusalem Bible, the Contemporary English Version, or the many others currently in print. One can wonder, however, whether the motivating factor in the multiplication and publication of such translations is the glory of God or the enlargement of publisher’s bankrolls. The awful truth is that Bible publishing is a huge profit-making enterprise, and most publishers seek to enlarge their profits by every means available, without regard for concepts such as sharing and ministry as a primary factor.

As an example, the New International Version was produced under the auspices of the International Bible Society, and was funded by the freewill gifts of God’s people and churches. That translation should have become freely available to God’s people with no restriction or royalty fees attached. Yet the exclusive rights to the NIV were transferred to the profit-oriented Zondervan corporation, which (due to the great popularity of the NIV) has imposed on other publishers some of the most outrageous license and royalty restrictions that have ever been attached to a translation.[14] Numerous Bible study tools marketed by Zondervan now bear the trademarked term “NIV” in the title, even if that translation is not the primary focus of such books the profit motive in this regard is obvious. Speaking as a Southern Baptist, even Broadman/Holman publishers have joined the vicious cycle by licensing the NIV as the base text of its New American Commentary series, with certain restrictions accompanying such a license which should not be tolerated in a commentary series.[15]

When Bible publishers start demanding $10,000 royalty fees, as well as a required sales quota merely to obtain a license to utilize a contemporary translation, something is clearly amiss. The people of God should never have been willing to barter away their rights to His precious word. When exactly did God’s people determine to surrender their rights to God’s word and to allow the publishing community to dictate its use to the churches? It is the publishers who should be paying the churches royalties for making profit from that word, rather than the reverse. If silver and gold interferes with the unrestricted use and dissemination of God’s word as the sacred scripture for the Christian community, it will be the copyright-holding publishers who will have to answer for their motives at the judgment.

The initial release of the English Revised Version of 1881-1885 was free of copyright in the United States and was intended for mass distribution. It was the first major revision since the 1769 Blayney revision of the King James in 1611. The day it was released, two major daily newspapers in Chicago printed the complete ERV New Testament text.[16] This was followed by a number of US publishers releasing editions of the ERV, with no restrictions attached.

When the American edition of the ERV was published 16 years later as the American Standard Version of 1901, matters somehow had changed. The American Revision (identical to the ERV except for the incorporation of various changes recommended by the American Committee) was copyrighted by Thomas Nelson & Sons Publishers with the enigmatic statement “To insure purity of text.” There was also a notice that Thomas Nelson & Sons was specifically “certified” to be the publisher of “the only editions authorized by the American Committee of Revision.” That copyright was renewed in 1929, but transferred to the International Council of Christian Education (the forerunner of the National Council of Churches) with both statements still attached. In fact, the original 1946 edition of the Revised Standard Version was also similarly copyrighted “to insure purity of text.”

Although it may be questioned what “purity of text” needed to be specifically “insured,” and it does not specify who the anticipated or real corrupters might have been, the answer is not long in coming. The prefaces to both the 1901 ASV and the 1946 RSV New Testament make the situation quite clear:

It was agreed that, respecting all points of ultimate difference, the English Companies, who had the initiative in the work of revision, should have the decisive vote. But as an offset to this, it was proposed on the British side that the American preferences should be published as an Appendix in every copy of the Revised Bible during a term of fourteen years. The American Committee on their part pledged themselves to give, for the same limited period, no sanction to the publication of any other editions of the Revised Version than those issued by the University Presses of England… It now [1901] seems to be expedient to issue an edition of the Revised Version with those preferences embodied in the text.[17]

Because of unhappy experience with unauthorized publications in the two decades between 1881 and 1901, which tampered with the text of the English Revised Version in the supposed interest of the American public [by placing the American preferences into the main text rather than in the Appendix], the American Standard Version was copyrighted, to protect the text from unauthorized changes.[18]

So the answer is plain: despite the American Committee’s agreement not to “give sanction” to any “unauthorized” editions of the ERV published in the United States, such publications did legally and freely occur, and in fact may have outsold the British printings of the ERV in this country. Rather than giving glory to God for the further dissemination of His word, the concern seems to have been with the apparent violation of the initial agreement more than anything else. Thus, beginning with the 1901 ASV, the copyrighting of biblical translations in the US became a matter of policy, even if by subterfuge. Although the copyright to the ASV 1901 was transferred in 1928 to the International Council for Religious Education, as noted, the original agreement allowed Thomas Nelson & Sons publishers to hold the initial copyright. Despite the protestations to the contrary, this was not due to any significant desire “to insure purity of text,” but was in fact a return for the Nelson company’s financial bailout of ASV Committee expenses to the then-hefty tune of approximately $25,000. The bailout was needed to cover the costs of preparing the American revision, since the American Committee significantly expanded upon the original changes enumerated in the 1881-1885 ERV appendix.[19] Thus, a modern policy of restricted access to the word of God was imposed, merely in order that the less-than-altruistic American publisher might financially benefit from an exclusive copyright. After 1901, the possibility of further danger to the “purity of the text” was probably insignificant, but the “protection” of that purity involved a granting of exclusive rights to a publisher by a translation committee which probably was not authorized to make such deals to the detriment of the people of God, but which in the absence of an external controlling body chose to seek its own best course.

Once the ASV 1901 had been successfully copyrighted in this country with no apparent legal challenge, the gate was opened, and nearly all subsequent Bible texts and translations followed suit. Permissions and royalty fees became the norm, since these were regularly required of all secular writings. But somewhere a great evil is involved whenever the people of God permit commercial publishers to hold hostage their sacred texts by copyright and licensing restrictions; for far too long the Christian community has been distracted from seeing the full implications of this matter, and the time is rapidly approaching when it may be too late to take reconstructive action.[20]

The word of God is itself the peculiar possession of the people of God.[21] It should never become the exclusive property of various publishers and license providers who offer to dole out divine revelation for a fee. The primary incentive for publishing the word of God should not be the engendering of profit for the hireling publisher, but that the people of God might use His word for both their own edification and the evangelization and discipling of the nations.

It is high time that the Christian community awaken itself to the situation and dispatch a loud and strong cry in order to reclaim the biblical text from those who have made it into proprietary merchandise. It is not the “purity of the text” which has to be protected, but the liberation of that text from those non-church entities who desire to profit unjustly from marketing God’s word back to God’s people, who should own and control the dissemination of that word in the first place. Our ministry to a dying world requires sanctuary from the profit motive in regard to our sacred texts.

The commercial copyright “owners” of biblical texts should at once freely and clearly release those texts back to God’s people for their unrestricted and unhindered use. There is more than one parallel case: whether the subject is musical composition,[22] or the editing, recording,[23] or live public performance[24] of biblical translations or original language texts, one either performs his or her labor first for the glory of God or for financial enrichment and personal glory. Publishers and copyright holders of material intended for Christian worship, evangelization, and ministry should desire (and request) little more than the basic cost of production and materials. To do otherwise is to forget the genuine concept of ministry, and to ignore the biblical admonition “Freely you have received — freely give” (Mt. 10:8)

(4) Unreasonable Limitations upon Fair Use

As if it were not sufficient for copyright holders to license the use of the biblical text for profit, many translational copyright holders have decided to further restrict the “fair use” of the biblical text itself by the people of God by adding limitations upon how much biblical text can be used at any given time. Some editions of the Bible are totally restricted just as any secular work by statements similar to the following:

All rights in this book are reserved. No part may be reproduced in any manner without permission in writing from the Publisher, except brief quotations and in connection with a review or comment in a magazine or newspaper.

Or again,

No reproduction of the material in this Bible may be made by photocopy, mechanical means, or in any other form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Additional restrictions attempt to dictate precisely how much of the Bible one can freely quote at any given time. The typical restriction notice will give permission to quote up to 200 (or 250, 500, or 1000) verses of the text of a given translation without seeking written permission from the publisher.[25] The accessory restrictions usually further state that, in quoting such verses, one is prohibited from quoting the complete text of any biblical book, and the portion quoted cannot exceed a certain percentage (usually 50%) of the text of the document containing such quotes. In other words, one can reproduce and quote the entire NIV/NASV/NKJV or other text from 1 John 1:2 through 2 John 12 without infringing, but woe to the person who might dare to cite 2 John 1- 13 on the back of a church flyer! Neither should anyone use any copyrighted translation in a gospel tract without obtaining formal permission from the copyright holder, lest he or she be sued for infringement for merely attempting to present the gospel as Christ commanded and quoting scripture more than 50% of the time. The obedient disciple of Jesus Christ should never have to seek permission to quote or reproduce any portion of Holy Scripture! The present writer renounces such restrictions, and cheerfully reproduces the entire “prohibited” text of 2 John from the NRSV at the end of this paper to illustrate the point.

The truth is, regardless of such authoritative-sounding statements, there are no precise restrictions or limits specified under present copyright law concerning what is normally termed “fair use.” There are tests which may be applied in court to determine whether a given quotation might overstep the boundaries of "fair use," but this would force a Christian to risk infringement merely to freely utilize the word of God in the manner which seems most appropriate. Secular courts should never have to rule in regard to “fair use” of biblical texts. The publishers should immediately drop all appended restrictions regarding the use of their translations which they have chosen to add to their copyright notices. By lording their exclusive copyright over all else, contemporary publishers now presume to dictate to their readers the precise limits under which their edition of the word of God may be utilized. The situation has degenerated to such a degree that one can even find false claims of copyright being issued, for no other reason except an attempt to obtain control and/or remuneration for what does not legitimately belong to the publisher.[26] This writer personally finds such restrictions abhorrent, and an attempt to further stifle the true “fair use” of God’s holy word.

(5) Conclusion

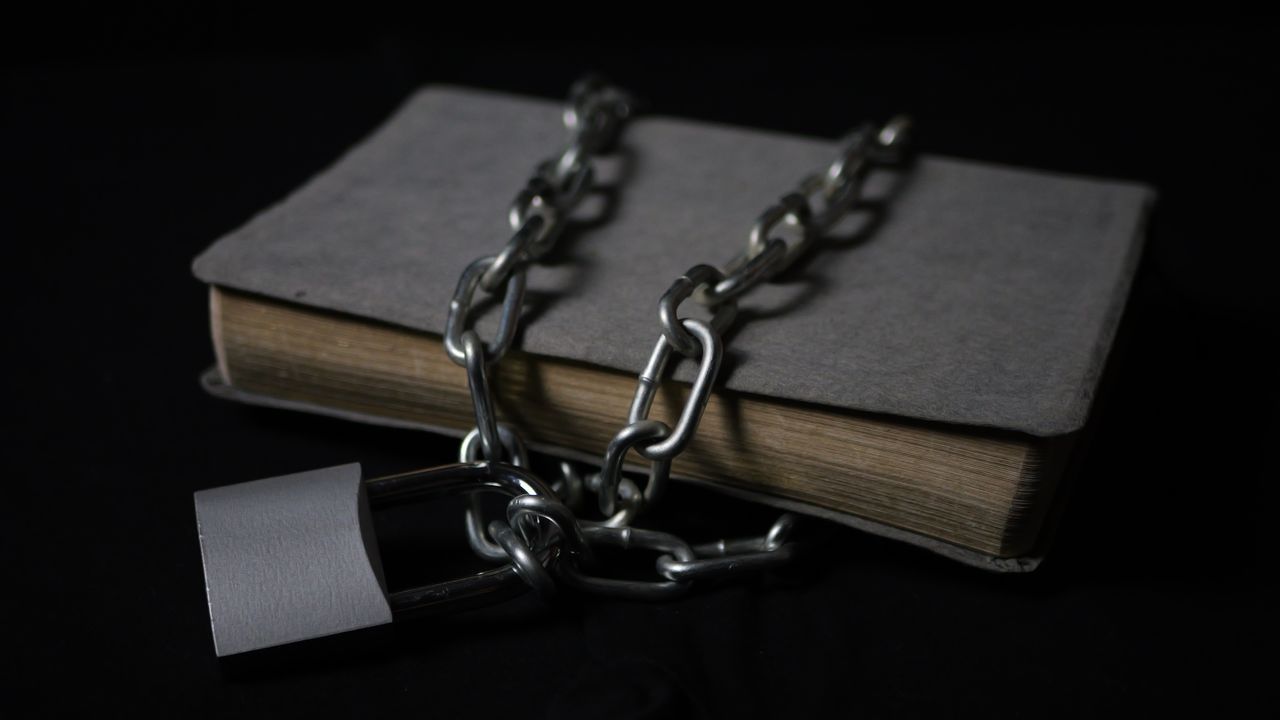

In summary, for nearly a century, copyright legislation has been subtly but effectively applied, misused and abused in regard to the word of God in order to chain the Bible to a new pulpit, differing in kind but not in essence from the restrictive practice so loudly decried in the Middle Ages. While the contemporary difference can be described in terms of dollars and cents, the net effect is identical: the free and unhindered access by God’s people to the revealed truth of His word is restricted once more, this time not by the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but by the chains of copyright and financial ransom as demanded by the proprietary publishers. Has God’s word all of a sudden ceased to be the “intellectual property” of God’s people? Must it now remain under the peculiar control of executives, scholars and lawyers?

In contrast, I find it commendable that Richard Francis Weymouth, when creating his own original translation entitled The New Testament in Modern Speech (5th ed., 1929, various publishers), permitted that work to be published with no notice or claim of copyright, even though it would have been legally possible for him so to have done. In comparison with all other modern versions, Weymouth’s magnanimous gesture passes almost unnoticed. Yet a great spiritual benefit is derived from quietly performing one’s work and releasing it solely to the glory of God with no anticipation of personal profit or remuneration. Such a quality is sadly lacking among the contemporary commercial publishers and even within the Bible Societies themselves, who are constituted expressly for the wide and economical distribution of the word of God. The abuses noted have a common link, and that is the desire to create profitable merchandise out of the word of God; such is nothing less than a deceitful handling of that very word which condemns such a practice. The judgment of God in regard to the profiteers is no different than that which Jesus and Paul declared so long ago:

“Take these things from here: do not make my Father’s house a house of merchandise” (John 2:16);

“We are not as the many, making merchandise of the word of God” (2 Cor 2:17);

“[We] have renounced the hidden things of shame, not walking in craftiness nor handling the word of God deceitfully” (2 Cor 4:2).

There is no need for negotiation concerning the contemporary “Bondage of the Word”; it already exists and there seems to be no sign that such abuse will diminish. Legislation and royalty fees to the contrary, and notwithstanding the legal chains and bonds which modern editors and publishers have attempted to impose, our Almighty God once and for all has declared that “the word of God is not bound” (2 Tim 2.9), and only from this perspective can anything truly be accomplished solely for the glory of God. Amen.[27]

Exhibit A: A Display of “Prohibited” Scripture

To exemplify the abuses imposed by copyright and subsequent restrictions, this page reproduces without seeking permission either orally or in writing the entire text of the book of 2 John — a direct violation of the restriction regarding the quotation of the copyrighted biblical text of the NRSV. The restriction is violated because an entire book of the Bible is quoted, in utter disregard of the specific NRSV restriction statement on the inside title page, which expressly states (emphasis added):

The NRSV text may be quoted and or reprinted up to and inclusive of five hundred (500) verses without express written permission of the publisher, provided the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book of the Bible nor account for 50% of the written text of the total work in which they are quoted.

Notice of copyright must appear on the title or copyright page of the work as follows:

“The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright, 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U. S. A. Used by permission. All rights reserved.”

When quotations from the NRSV text are used in non-saleable media, such as church bulletins, orders of service, posters, transparencies, or similar media, the initials (NRSV) may be used at the end of each quotation.

Quotations or reprints in excess of five hundred (500) verses (as well as other permission requests) must be approved in writing by the NRSV Permissions Office, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.

The real absurdity to this entire excursus is that no permission would have been required to quote the far more extensive passage from 1 Jn 1:2 all the way through 2 Jn 12. However, the mere reproduction of the thirteen verses which appear below is prohibited. Regardless of restrictions, however, here now is the entire text of 2 John from the NRSV — used without seeking any permission whatsoever:

The Second Letter of John

1 The elder to the elect lady and her children, whom I love in the truth, and not only I but also all who know the truth, 2 because of the truth that abides in us and will be with us forever.

3 Grace, mercy, and peace will be with us from God the Father and from Jesus Christ, the Father’s Son, in truth and love.

4 I was overjoyed to find some of your children walking in the truth, just as we have been commanded by the Father. 5 But now, dear lady, I ask you, not as though I were writing you a new commandment, but one we have had from the beginning, let us love one another. 6 And this is love, that we walk according to his commandments: this is the commandment just as you have heard it from the beginning you must walk in it.

7 Many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh: any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist! 8 Be on your guard, so that you do not lose what we have worked for, but may receive a full reward. 9 Everyone who does not abide in the teaching of Christ, but goes beyond it, does not have God: whoever abides in the teaching has both the Father and the Son. 10 Do not receive into the house or welcome anyone who comes to you and does not bring this teaching: 11 for to welcome is to participate in the evil deeds of such a person.

12 Although I have much to write to you, I would rather not use paper and ink: instead I hope to come to you and talk with you face to face, so that our joy may be complete.

13 The children of your elect sister send you their greetings.

Originally delivered in a slightly different format as the Fall Faculty Lecture, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wake Forest, North Carolina, 24 October 1995. Some revisions and errors of fact also were corrected following the ETS meeting at which this present paper was presented. ↩︎

US Constitution, Art. 1, Sec. 8. ↩︎

Expressed in a public posting addressed to the present writer by Harold P. Scanlin of the American Bible Society which appeared on the internet TC-List (text-critical listserver), 15 April 1996. Scanlin specifically stated, "It is not my intention to enter into a legal debate, but I just want to state that it is the position of the Bible Societies that an eclectic text and the accompanying critical apparatus is ‘intellectual property’ and subject to copyright protection. I look forward to any forum such as the upcoming ETS meeting where this issue can be discussed.” This writer would note that the point under discussion is only the biblical text itself (eclectic or otherwise), and not the accompanying apparatus, introductions, or appended matter. ↩︎

Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart, GBS, 1994). The first edition was published by the United Bible Societies, London, 1975. ↩︎

US Supreme Court, 1282, 1287-88 (1991). Decision on appeal from Rural Telephone Service Co. v. Feist Publications, Inc., 737 F. Supp. 610, 622 (Kan. 1990). ↩︎

In the Feist decision, Sandra Day O’Connor, writing for the majority, noted that in what was “known alternatively as ‘sweat of the brow’ or 'industrious collection, the underlying notion was that copyright was a reward for the hard work that went into compiling facts… [But] the ‘sweat of the brow’ doctrine had numerous flaws… A subsequent compiler was ‘not entitled to take one word of information previously published,’ but rather had to 'independently work out the matter for himself, so as to arrive at the same result from the same common sources of information. Id., at 88-89 (internal quotations omitted). ‘Sweat of the brow’ courts thereby eschewed the most fundamental axiom of copyright law that no one may copyright facts or ideas… Decisions of this Court applying the 1909 Act make clear that the statute did not permit the ‘sweat of the brow’ approach… [In the case of] International News Service v. Associated Press, 248 U.S. 215 (1918)… the Court stated unambiguously that the 1909 Act conferred copyright protection only on those elements of a work that were original to the author… In enacting the Copyright Act of 1976, Congress dropped the reference to “all the writings of an author” and replaced it with the phrase “original works of authorship.” 17 U.S.C. Sec. 102(a). In making explicit the originality requirement, Congress announced that it was merely clarifying existing law: The 1976 Act [added] Sec. 102(b), [which]… identifies specifically those elements of a work for which copyright is not available: 'In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.’” ↩︎

Justice O’Connor in the Feist decision further notes that “originality is a constitutional requirement,” and “there can be no valid copyright in facts.” She continues, “The mere fact that a work is copyrighted does not mean that every element of the work may be protected. Originality remains the sine qua non of copyright; accordingly, copyright protection may extend only to those components of a work that are original to the author [even though] . . . . it may seem unfair that much of the fruit of the compiler’s labor may be used by others without compensation.” ↩︎

Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont, eds. The Greek New Testament according to the Byzantine/Majority Textform (Atlanta: Original Word, 1991). The Greek text of that edition was initially released into the public domain in 1987 as electronic freeware by means of the Online Bible computer program (West Montrose, Ontario: Timnathserah, 1987). ↩︎

To quote Justice O’Connor in Feist once more: "The most important point here is one that is commonly misunderstood today: copyright… has no effect one way or the other on the copyright or public domain status of the preexisting material.’ H. R. Rep., at 57; S. Rep., at 55…. Even those scholars who believe that “industrious collection” should be rewarded seem to recognize that this is beyond the scope of existing copyright law… Brief for Respondent 17. Section 103(b) states explicitly [p*362] that the copyright in a compilation does not extend to ‘the preexisting material employed in the work.'… This is ‘selection’ of a sort, but it lacks the modicum of creativity necessary to transform mere selection into copyrightable expression.” ↩︎

Citing the Feist decision: “Rural expended sufficient effort [p*363] to make the white pages directory useful, but insufficient creativity to make it original… there is nothing remotely creative about arranging names alphabetically in a white pages directory… As a constitutional matter, copyright protects only those constituent elements of a work that possess more than a de minimis quantum of creativity.” The same principle would appear to apply in a situation where a selection of readings taken from a given fixed list is made, since the final resultant pattern of the entire text still remains essentially the same as previous editions now in the public domain (e.g. Westcott and Hort as compared to Nestle-Aland27). ↩︎

According to Henry Otis Dwight, The Centennial History of the American Bible Society. 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1916), the Bible Societies since their beginning have erroneously and arrogantly considered that they alone, and not God’s people within Christ’s Church are the custodians and guardians of Holy Writ: “In all questions of the accuracy and propriety of versions the Bible Society must satisfy itself, for it will be held responsible for whatever goes forth published in its name. . . . The responsibility of the Bible Society for the English version is everywhere understood. As President J. Cotton Smith remarked in his address at the Annual Meeting of the Society in 1836: ‘The Society is charged with the preservation, not only of the truths of the English Bible but of its precise language.’ An interdenominational Society only can properly secure the text against alteration; it being a body trusted by all denominations, it watches over the inviolability of the text. A copy bearing the imprint of such a Society is of guaranteed authenticity.” (vol. i., p. 132). Dwight further states on the same page, “Only after Bible Societies became established could one feel that an authoritative control guaranteed the new editions as they came from the press.” One need only note that today most publishers are not exactly seeking the approval of the Bible Societies before publishing their proprietary translations. Only those translations specifically commissioned and copyrighted by the Bible Societies (e.g. TEV, CEV) are “protected” by licensing restrictions and royalty requirements to those publishers who contract for their use. ↩︎

Since the widest possible low-cost distribution of scripture texts and translations is indeed the purpose of the Bible Societies, and since the advent of electronic media has reduced the cost of certain forms of “publication” to almost zero, one should rightly wonder why the Bible Societies would ever seek to restrict the wider dissemination of biblical texts and translations by charging license and royalty fees and claiming “intellectual property” rights over any form of God’s word, to which they themselves should be subject, and not vice versa. ↩︎

Note that this is not intended in any way to deprecate the scholarship or industry of those who have labored and used their knowledge of the original languages to produce such modernized renditions. It is true, however, that even without the application of such scholarly acumen a text which is 95% identical to the NKJV could be produced by simple modernization. The primary possibility for observable “new” scholarship in the resultant text in such situations remains minimal, and is not often observable even within the 5% of the text which might differ from the original translation. ↩︎

One software publisher (here “Mr. J”, though I know his real name) told me via the internet that his request for a license to use the NIV in his proposed product was denied due to his inability to guarantee a minimum sales quota of $10,000 worth of copies per year, even though he would have been able to pay the required $10,000 up-front licensing fee as well as the subsequent percentage royalty fee for sales. The absurdity of this licensing arrangement is further compounded by the fact that, in the time since the Zondervan corporation originally obtained the rights to the NIV, that corporation has been sold and is now a subsidiary of the secular Harper/Collins publishing chain, which is a part of the same conglomerate owned by Rupert Murdoch, which includes Fox Broadcasting. Mr. J also sought a similar permission from the American Bible Society “to publish the TEV, CEV, and Versión Popular, in electronic form, either for free or for any royalty fee (reasonable or unreasonable).” His report is disheartening: "Feel free to relate the ABS absolute denial of my request (on behalf of Rainbow Missions, Inc.). . . . They had decided not to grant my request, based on the lack of security of my Internet distribution method. (Horrors! Someone might read the Gospel without paying for it!).” Even after communicating assurances of security due to encryption technology, Mr. J was again refused permission, with a message from the Bible Society to the effect “that they had decided not to let anyone have electronic rights to publish their Bible texts (including, I presume, the foreign language texts that they act as copyright representatives for in the USA), but that if they were published at all, that they would do it themselves.” Mr. J’s comments to me declare a well- founded exasperation: “Frankly, I feel like I’ve been ripped off, having contributed to the ABS based on their stated purpose of ‘providing the Holy Scriptures to every man, woman, and child in a language and form each can readily understand, and at a price each can easily afford.’ I fail to comprehend how these go together. This action does not match their mission statement very well.” ↩︎

Although the royalty fee for use of the NIV in a commentary is relatively low (a few hundred dollars one-time payment per volume in the commentary series which is not dependent upon the number of copies sold), there still are certain guidelines with which commentary authors have to concur before writing their comments. Included among these is a requirement that direct criticism of the NIV rendering is not permitted within the commentary text, and also that Zondervan reserves the right to review all comments to make certain that this guideline is followed strictly. Such an imposition on the academic freedom of a commentator in effect makes that commentator a marketing shill for Zondervan and not a true commentator such has historically existed who always should remain free to criticize or suggest improvements to the text of any translation whenever such might be justified. This Zondervan licensing requirement is most definitely an unacceptable burden imposed upon any commentator worthy of the name. ↩︎

Klaus Penzel, ed., Philip Schaff. Historian and Ambassador of the Universal Church: Selected Writings (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1991), chapter 7, “The Revision of the English Bible,” p. 267. ↩︎

The Holy Bible. Newly edited by the American Revision Committee, A. D. 1901 (New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1901), “Preface,” p. iii. ↩︎

The New Covenant, Commonly called the New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Revised Standard Version (New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1946), “Preface,” pp. iii-iv. Penzel, Philip Schaff, p. 261, n.29, points out that the fault did not lie solely with various American publishers tampering with the non-copyrighted biblical text of the ERV, but that “Unauthorized Bible Versions incorporating the American Appendix [into the main text] had already been published… without prior consultation with the American revisers, by the English University Presses in 1898”! ↩︎

ASV “Preface,” p. iv: "In now issuing an American edition, the American Revisers, being entirely untrammelled by any connection with the British Revisers and Presses, have felt themselves to be free to go beyond the task of incorporating the Appendix in the text, and are no longer restrained from introducing into the text a large number of . . . suppressed emendations.” Regarding the Nelson buyout of the ASV copyright, see Penzel, Philip Schaff, pp. 251-271. (Philip Schaff was President of the American Revision Committee). The financial matters regarding the American Committee which led up to the Nelson buyout are partially detailed on pp. 256-257 and p. 261, n. 29. Significantly, the American Committee initially considered the copyright issue “an unwarranted intrusion of a legal question (copyright) into a moral question (joint responsibility)” (p. 257). ↩︎

Current proposed alterations to the copyright law may soon increase the restrictions currently in place by extending copyright for an additional twenty years, as well as increasing the likelihood of infringement claims, even on works which are public domain, once such works are placed in an electronic database. One proposed item now under consideration would even make facts such as ball game scores proprietary, and unable to be reported by news media without a payment to, e.g., the NFL or Major League Baseball. What the end result of “intellectual property” legislation and litigation will be in the next century is unknown, but the prospects appear dangerously dim, and we all stand to lose something very valuable in regard to information technology due to legislative maneuverings in the interest of unjust profit alone. ↩︎

The Westminster Confession of Faith offers a typical comment to this effect: “It pleased the Lord, at sundry times and in divers manners, to reveal himself, and to declare that his will unto his church; and afterward, for the better preserving and propagating of the truth, and for the more sure establishment and comfort of the church against the corruption of the flesh, and the malice of Satan and of the world, to commit the same wholly unto writing, which maketh the holy scripture to be most necessary” (Article 1, “Of the Holy Scripture”). Emphasis added. ↩︎

As a sometime Christian composer, I would editorially suggest the same for those who ostensibly write music “for the glory of God” but who then demand copyright-based ransom fees from our churches (whether by CCLI or other licensing arrangements) merely in order that God’s people can praise Him in public worship by displaying the lyrics to simple choruses (many of which are mostly bible text!) on an overhead projector during worship. While “the laborer is worthy of his hire,” and deserves just compensation for the initial sale and recording of music for commercial purposes, it remains absurd for such a composer to claim that “God gave me this song” and then demand compensation for what is specifically claimed to be God’s revelation. But in public worship, the people of God should freely praise Him with any psalms, hymns or spiritual songs with no license or copyright restrictions to hinder such worship. Christian songwriters and musicians had better sort out their priorities and decide whether for public worship (at the very least) their music is freely dedicated to God’s people for the glory of God and God alone or whether the ultimate object is personal financial profit. Our Lord made no idle comment when he declared “Do not make my Father’s house a house of merchandise!” Had the proper spirit been in place from the beginning, there would have never been a need for the Christian Musical Thought Police to monitor copyright claims by CCLI or similar unbiblical licensing arrangements. ↩︎

Since the present writer intends to maintain his own policy, he includes the public domain release of his own edited version of the Byzantine Greek Textform in electronic or other media, including a complete Digital Audio Tape recording of that same text, made in a professional studio environment (Greg House Studios, Wichita, Kansas) during the past two years, in which studio time, engineering, master tapes and personal reading were fully donated by all parties in order that God’s people might freely benefit from non-copyrighted and royalty-free biblical texts in multiple media. ↩︎

I allude to a situation in which a Christian radio disk jockey intended to stage a media event wherein 300 people would read different portions of the Bible simultaneously in a public setting for 15 minutes, thus completing the reading of the entire word of God in that short time. The DJ desired to use the Contemporary English Version published by the American Bible Society and sought their permission to do so, expecting that they would be excited about any such project which would give media attention to the word of God. On the contrary, the Bible Society refused his request, and he opted to use the public-domain KJV instead (reported to this writer via internet e-mail by the DJ in question). ↩︎

See Exhibit A appended to this paper for a complete sample restriction notice, taken from the inside title page of the NRSV. ↩︎

One of the most blatant claims of false copyright can be seen in The Holy Bible: King James Version (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1995), which states on the inside title page “Copyright © 1995 by Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49530 USA. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved” even though the entire book contains only the title page, table of contents listing the biblical books in alphabetical order, and the entire public domain KJV text unaltered, without note or comment. There is nothing copyrightable in the entire product! Attorney/Professor Paul J. Heald speaks directly to this point in Paul J. Heald, “Payment Demands for Spurious Copyrights: Four Causes of Action,” Journal of Intellectual Property Law 1 (Spring 1994) 2:259-292. Heald concludes, “Unless publishers are made to bear the cost of their misrepresentations, they will have no incentive to remove false copyright notices from the works they sell. Nor will they have any incentive to cease the sort of intimidation consumers confront whenever they seek to photocopy a text. Successful actions brought on the grounds… [of] breach of warranty, unjust enrichment, fraud, and false advertising . . . might help stem the tide of misrepresentation and confusion. This is especially true if courts… exercise their prerogative to award punitive or other augmented damages and attorneys’ fees. Until the publishing industry is jolted into compliance with sound public policy, consumers will continue to be induced to part with their money by spurious claims of copyright” (pp. 281-282). ↩︎

It is noteworthy that the Muslims tend to consider the text of the Qur’an as public domain, and this even in translation. Whereas some commercial translations of the Qur’an are copyrighted and restricted by publishers in much the same manner as English Bible translations, other translations such as that by M. H. Shakir (The Qur’an, [Elmhurst, NY: Tahrike Tarsile Qur’an Inc., 1995]) claim no copyright on the translation, and specifically state that their publishing house is “a nonprofit religious organization… devoted to the dissemination of authentic knowledge concerning Islam through the sale and free distribution of copies of holy Qur’an and its translation.” This parallels that which the Bible Societies are supposedly thought to emulate, but with significant differences of opinion regarding the text considered to be sacred. Similarly, the translation based upon (but not identical to) that of J. M. Rodwell from the 19th century (The Koran [New York: Ivy Books, 1993]) also claims no copyright, despite a modernization of language and syntax in a manner paralleling that of the NKJV and NASV. ↩︎