Executive Summary – The rapid expansion of the global church has created an urgent need for Bible translations and biblical content that lead to sound interpretation of Scripture and formation of faithful theology in every culture and people group. The most effective means of meeting this immense need is by the collaboration of the global church in an interdependent and highly scalable manner. This requires minimizing the legal friction intrinsic to the default “all rights reserved” licensing model, by making the needed content available under open licenses. This paper answers many of the objections that are raised by those desiring to open license resources and describes a strategy that equips the global church for freedom.

1. Introduction

The vision that motivates the writing of this paper is a world in which the entire global church—across all people groups and languages—can freely share freely excellent Bible translations and other biblical resources, without limitations on their retention, reuse, revision (whether by translating, extending, or adapting for effective use), remixing (by combining with other material to create new resources), and redistribution. This paper is written with the intent of addressing certain misunderstandings about the need for unrestricted biblical content in every language, different models for meeting that need, the nature of copyright law, and how “open” licenses work.

This paper has a limited scope. It describes the factors that may hinder content owners from participating in the “free and open” paradigm of world missions, but it does not provide a complete consideration of the paradigm itself. It makes little (or no) attempt to cover ground that I have addressed in other works, including:

- The biblical, missiological, and technological rationale for unrestricted biblical resources in every language: The Christian Commons (ufw.io/tcc).

- The description of an exponentially-scalable strategy to make unrestricted biblical resources available in every language: “The Gateway Languages Strategy” (ufw.io/gateway).

- The factors that predispose the global church to achieve excellence in translation of the Bible and creation of their own biblical resources: “Trustworthy and Trusted” (ufw.io/trustworthy) and “From Unreached to Established” (ufw.io/established).

My intent in this paper is not to criticize any licensing model, but to help those who desire to push biblical content over the wall of restrictions into the “free and open” world by pointing out the hindrances that prevent it from happening and describing how to overcome each one. Furthermore, participation in this movement is only ever a voluntary choice on the part of content owners and I am not suggesting that those who do not participate are in the wrong. Even when those who own biblical resources understand all the hindrances, they are not thereby obligated to make their content available under open licenses—it is their legal property and they have the right to do with it as they believe God would have them do.

Finally, it is important to declare up front that I am not an attorney and nothing in this paper constitutes legal advice. I am grateful for the ongoing counsel from IPR attorneys and legal scholars who continue to inform my understanding of copyright law and a biblical theology of property ownership. Their gracious assistance has greatly improved this paper but carries no implication of responsibility or endorsement on their part.

2. The Context

This paper focuses primarily on the “what” and “how” of biblical content and licensing, but it runs the risk of miscommunication unless the context (the “why”) is clearly understood. This section addresses four key aspects of the context: (2.1) the expansion of the global church which gives rise to (2.2) increased need for biblical content. This need could be effectively met using (2.3) the new technologies of an increasingly globalized world, but is hindered by (2.4) the restrictive licenses that are the default due to copyright law.

2.1. The Expansion of the Global Church

The global church is multiplying rapidly. Church-planting movements continue to expand the church at a rapid pace, shifting the center of Christianity (in terms of numerical growth) to the south and the east.

Over the last century, the center of gravity in the Christian world has shifted inexorably away from Europe, southward, to Africa and Latin America, and eastward, toward Asia. Today, the largest Christian communities on the planet are to be found in those regions (Jenkins 2011:1).

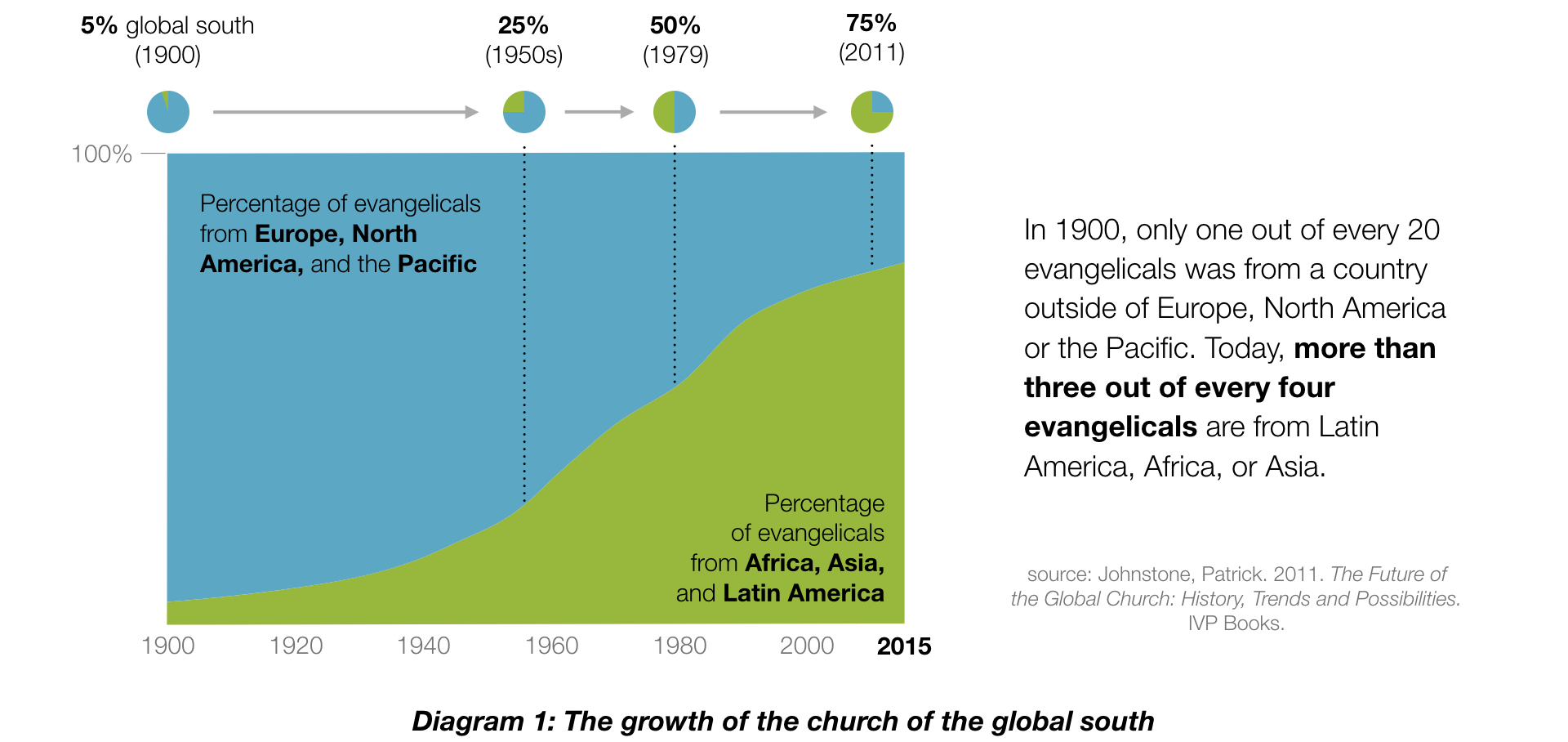

This transition can be seen in the following diagram that shows the percentage of evangelicals in the “global south” (Africa, Asia, and Latin America) compared to the “global north” (Europe, North America, and the Pacific) over the last century.

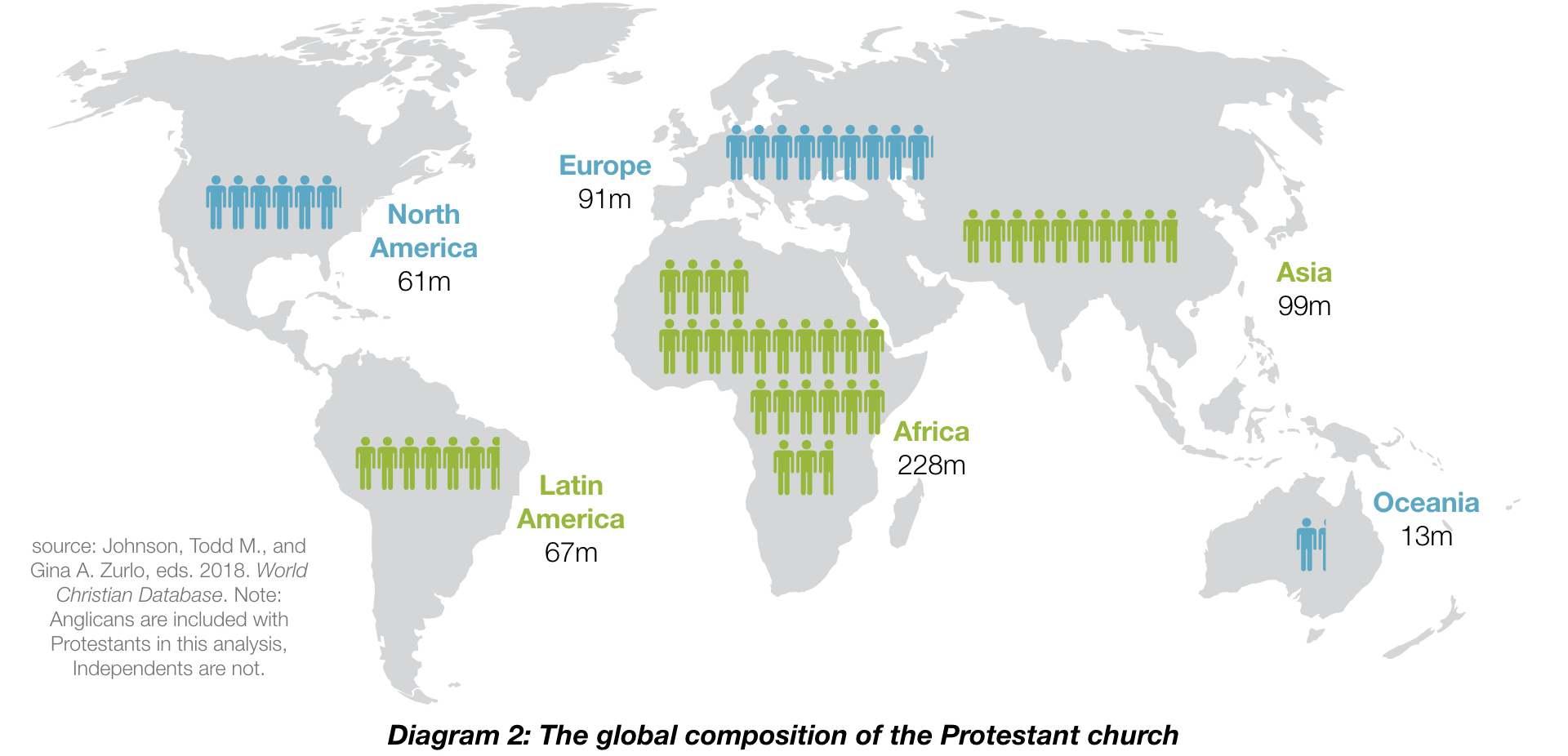

The composition of the global church today (in terms of the approximate number of Protestants) is depicted in the following diagram.[1]

2.2. The Need of the Global Church

In terms of numerical growth through evangelism and church planting, it is clear the church of the global south is expanding rapidly. But in terms of access to Bible translations and theological resources that make possible sound hermeneutics and accurate interpretation of Scripture, it is generally lagging far behind. These essential tools are available to only a small fraction of the global church, and then only to those who have the means to acquire them and speak one of the few languages in which they are available (usually English). This means that front-line leaders of local churches all over the world who urgently desire to become doctrinally sound and confidently teach faithful theology within their own cultural contexts are cut off from the wealth of biblical knowledge that is available only to a privileged minority. The foundational need, then, can be described like this:

The task… is to precipitate in each lingual church[2] the capacity to perpetuate knowledge of interpretation. This includes direct access to the original languages of the Bible and the fundamental principles of translation, hermeneutics and the cultural and historical context of the Bible. When a lingual church has this capacity, not completely in and of themselves, but in the interdependent manner supported by the global church and academia, they are well-equipped to provide and preserve the Bible and theological resources in their language (Griffin and Price, 2018, emphasis added).

What kinds of resources might be helpful for sound hermeneutics and reliable interpretation of the Bible? In addition to trustworthy translations of the Bible, Carson suggests the value of study notes “explaining cultural, religious, ecological, and linguistic points, especially in Bibles designed for groups made up largely of first readers who thus have very little knowledge of the biblical world” (provided that the notes are “as theologically neutral and objective as possible”, 2003, ch. 3). Fee and Stuart suggest that good exegesis is promoted by the use of “a good translation, a good Bible dictionary, and good commentaries” (2014:33). Osborne describes deductive study as building upon grammatical, semantical, and syntactical study and is where “all the tools—grammars, lexicons, dictionaries, word studies, atlases, background studies, periodical articles, commentaries—are consulted in order to deepen our knowledge base regarding the passage and to unlock the in-depth message under the surface of the text” (2010:30-32). As I have observed elsewhere, the need for these kinds of resources is acutely felt (2018:9):

Church leaders around the world consistently maintain that… they need the entire New Testament, then the entire Old Testament (not always in that order), study notes for the entire Bible, a Greek New Testament and Hebrew/Aramaic Old Testament (together with corresponding grammars and lexicons) available as interlinears in print and digital formats, then a commentary that further elucidates the author’s intent and context of the original recipients.

Essentially, the need is for equality across the entire global church—in every people group and language—in the realm of biblical study and theological formation. It is an appeal for all who trust in Jesus Christ and love His Word to be able to share together of the very best biblical, exegetical, and hermeneutical resources. In terms of the amount of content needed in every language to make this possible (whether in text or audio formats), the need is immense. This diagram is an approximation of the potential amount of biblical content (vertical axis) that could be needed in every language (horizontal axis).[3]

2.3. The Opportunities of the 21st Century

The 21st century is bringing with it profound changes, many of which constitute significant opportunities to meet the massive need of the global church for biblical content. Globalization continues to increase the life expectancy and general standard of living of many. These economic improvements are expanding and, in turn, being further improved by the global reach of mobile technology. Freeland observes:

“Today, two terrifically powerful forces are driving economic change: the technology revolution and globalization… together they constitute a dramatic gearshift comparable in its power and scale to the industrial revolution… What these twin transformations have done is trigger an industrial revolution–sized burst of growth in much of the rest of the world—China, India, and some other parts of the developing world are now going through their own gilded ages” (2012:4, emphasis added).

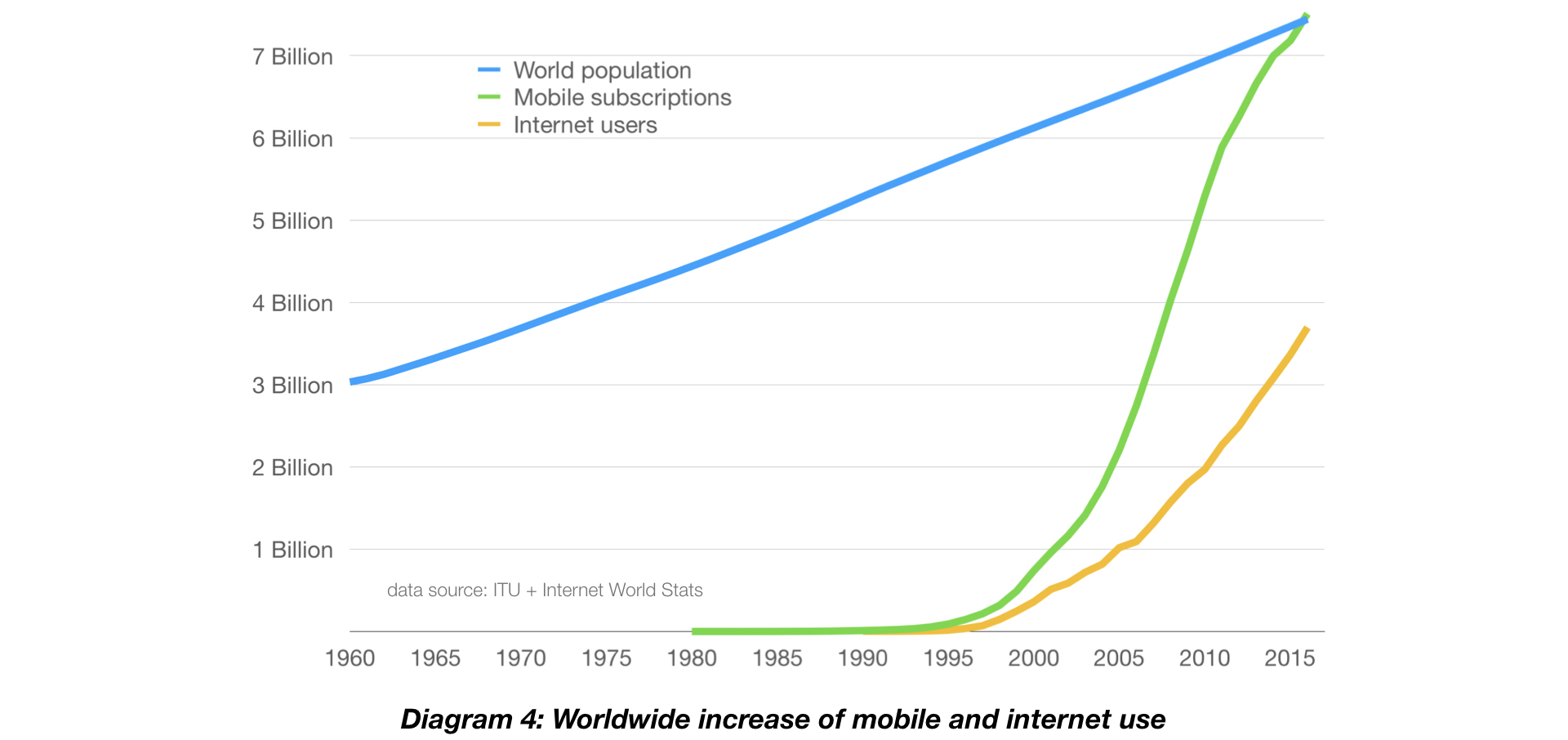

Two-thirds of the world now have a mobile phone, and over half of the world uses the internet.[4] This growth in internet-connected mobile technology can be seen in the diagram below that shows the mobile and internet use (vertical axis) over time (horizontal axis).

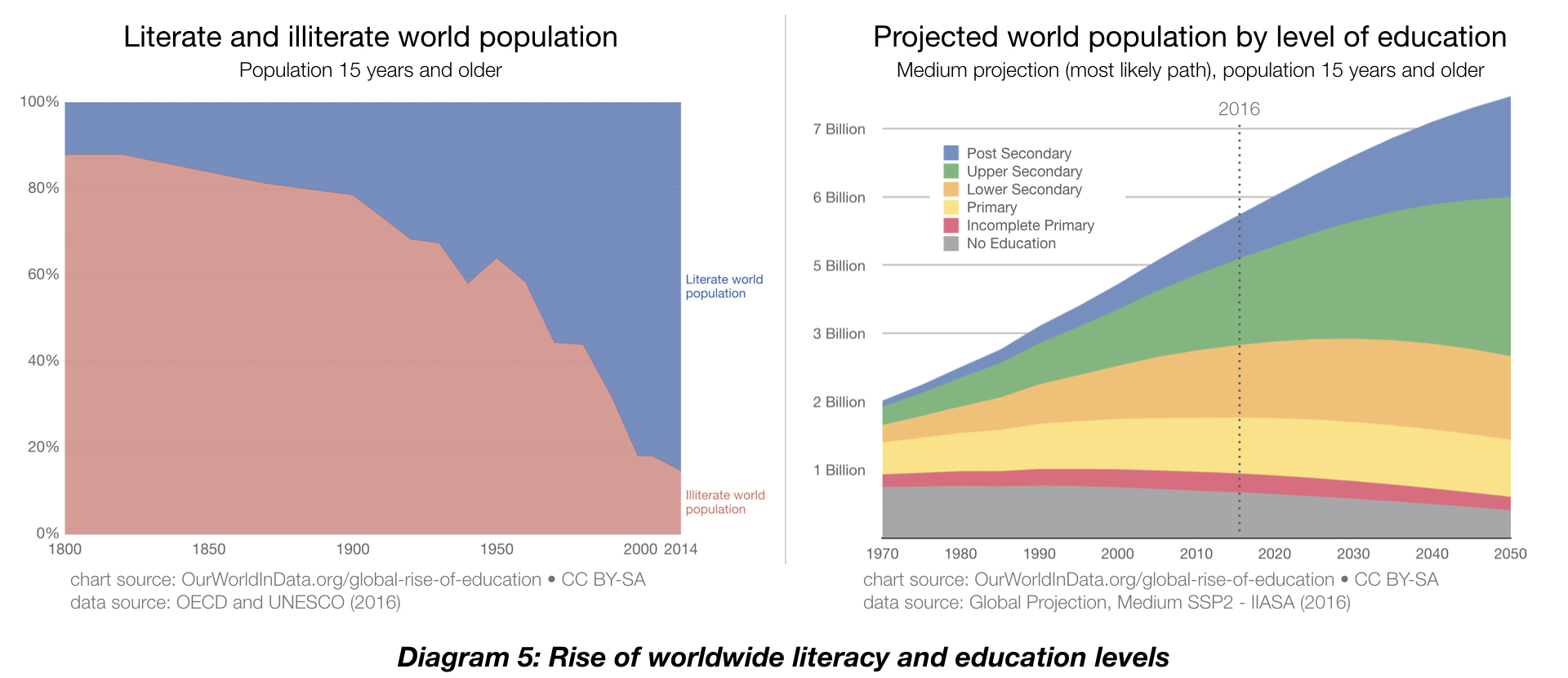

Global education levels also continue to rise. The diagram below shows the increase in global literacy levels in the past two centuries, as well as global education levels (within the last few decades and projecting forward). Note: these charts should only be seen as indicators of general trends, as even the best data on global literacy and education can be misleading.[5]

As globalization creates more job opportunities in cities, urbanization continues to increase, with approximately 55% of the world living in cities.[6] Urbanization and the increasing levels of education and technology use lead to more people using a common language in order to communicate. Consequently, this has increased the level of multilingualism such that it is generally the norm worldwide. De Swaan observes that a growing number of speakers of majority languages are multilingual:

There are those whose native speech is one of the peripheral languages and who in due course have acquired the central language. In fact, everywhere in the world the number of this type of bilinguals is on the increase, as a result of the spread of elementary education and of the printed word, as well as of the impact of radio broadcasting (2011:57, emphasis added).[7]

Perhaps the most important opportunity of the 21st century for the equipping of the church in every people group is the emergence in many parts of the world of influential and highly motivated church leaders who are taking responsibility for meeting the Bible translation and theological formation needs of the people within their own countries and spheres of influence. Many of them are highly educated, all of them are bilingual in Gateway Languages and they are proactively seeking to establish the churches in sound doctrine and with mature leadership. To the extent that they (and the leaders in their networks) are equipped with the biblical content, technology tools, and training resources in a language they understand well, the capacity of the entire global church can be activated to meet the immense need for Bibles and other biblical resources in every language.

But we run into a significant obstacle at this point, because the use of Bible translations and other biblical resources is governed by copyright law. As we shall see, the advantages and opportunities of the 21st century for the equipping of the church in every people group are often impeded by these laws that were designed for a previous era.

2.4. The Reality of Copyright Law

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization, 176 countries are signatories of The Berne Convention. Because of this (and with a few exceptions), copyright law functions in a similar manner worldwide. The following are the main points that work the same for these countries.

Copyright reserves all rights for the owner – Copyright law is designed to establish state-sanctioned and globally-applicable[8] control over the use of content by its creator in order to increase its commercial value and maximize the potential for its monetization.[9] The original intent of these restrictions was to encourage further innovation and creativity that would benefit society, so it was originally limited to fourteen years.[10] The Berne Convention states in Article 8:

Authors… shall enjoy the exclusive right of making and of authorizing the translation of their works throughout the term of protection of their rights in the original works.

and in Article 12:

Authors… shall enjoy the exclusive right of authorizing adaptations, arrangements and other alterations of their works.[11].

Copyright lasts for (more than) a lifetime – Over time, the term of copyright has been extended considerably. The Berne Convention stipulates that the duration of the term for copyright protection is the life of the author plus at least 50 years after their death (Article 7).[12]

Copyright starts at the point of creation – The “all rights reserved” of copyright starts at the point the content is created, even if the creator of the work is not aware of it or does not necessarily want it to be so.[13]

Copyright requires a license for use of content – In general, copyright law tends to forbid what is not explicitly permitted. With regard to replication, adaptation, and creation of derivatives (including translations), use of copyrightable content that still enjoys copyright protection and that is owned by someone else requires a license that grants explicit permission to do so. In this regard, the default answer to the question, “Can I do _____?” is “No” until (and unless) permission is granted otherwise.[14] This can be seen in a traditional copyright statement:

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher.

The implications of copyright law for the translation of the Bible and other biblical resources are significant: most of the biblical resources that could otherwise be useful to the global church for translation of the Bible and creation of other biblical resources are governed by licenses that greatly restrict their usefulness.[15]

3. Meeting the Need of the Global Church

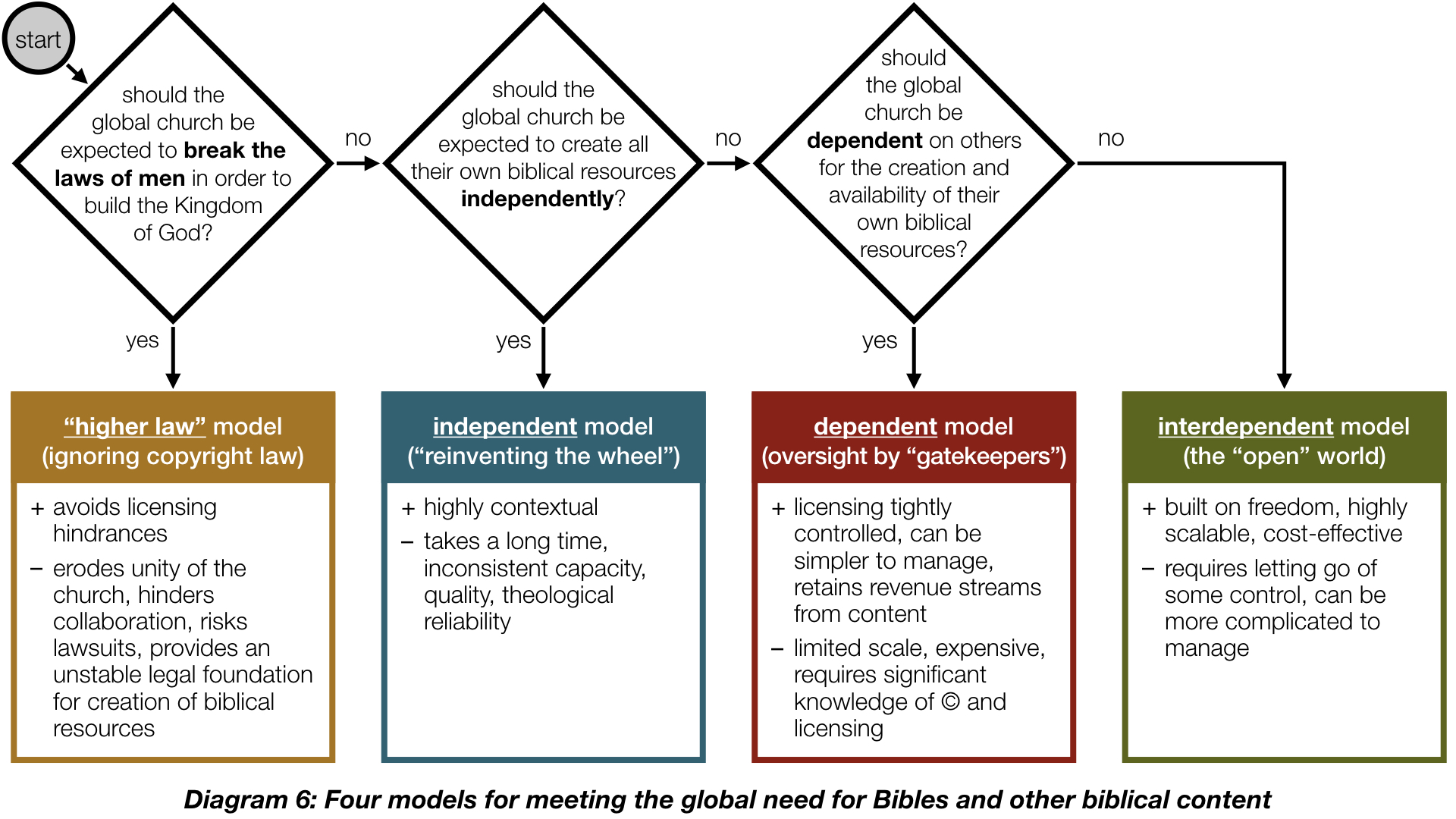

There are at least four ways that copyright law can be approached when it comes to the translation, adaptation, redistribution, and use of biblical content in every people group and language:

- The “Higher Law” Model (Ignoring Copyright Law)

- The Independent Model (“Reinventing the Wheel”)

- The Dependent Model (Oversight by “Gatekeepers”)

- The Interdependent Model (The “Open” World)

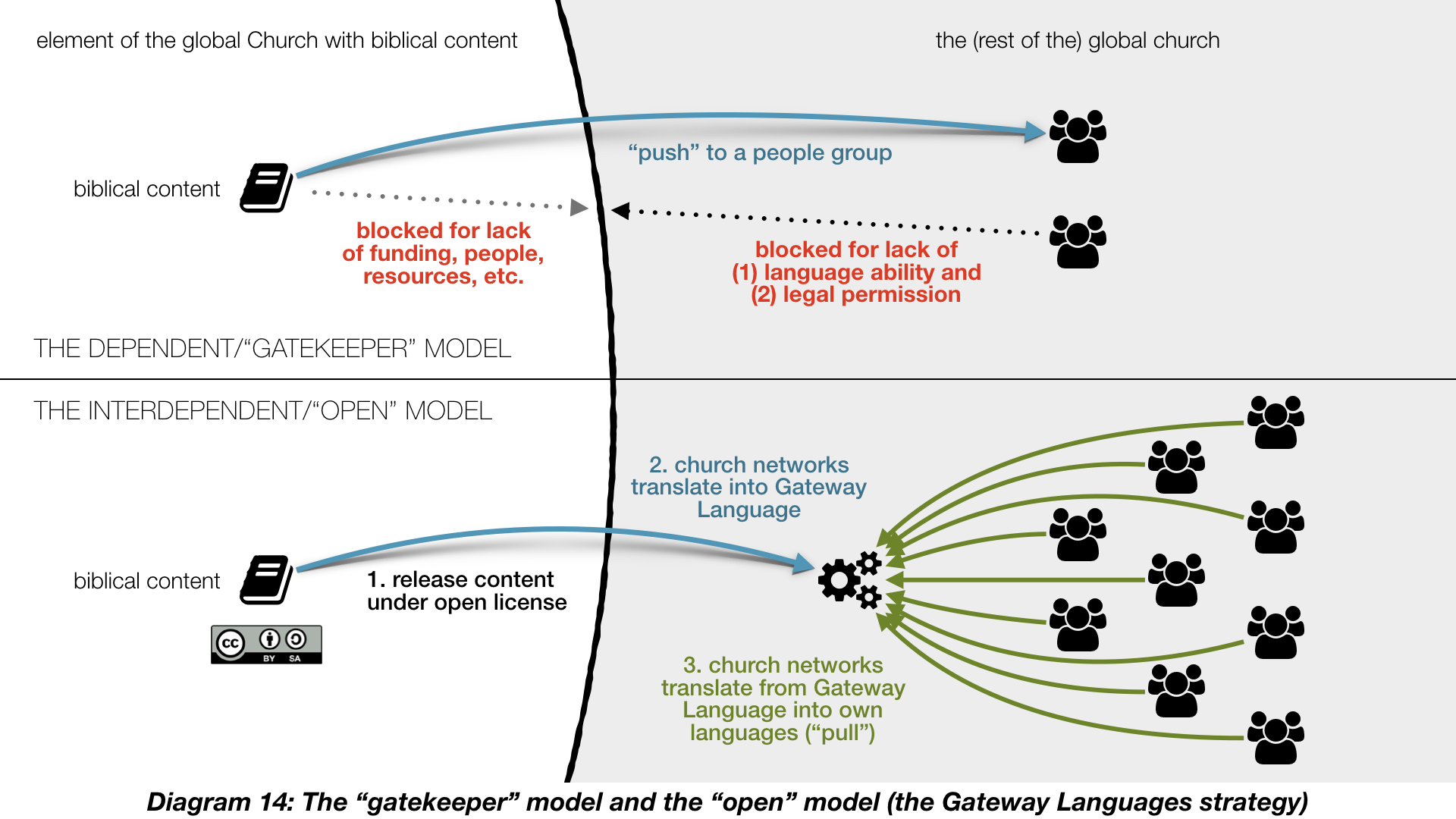

These four models can be considered as a flowchart, as in this diagram.

3.1. The “Higher Law” Model (Ignoring Copyright Law)

There is precedent in Scripture for Christians to disregard the “laws of man” in order to obey God. In response to the Jewish leaders’ demands that they stop preaching in the name of Jesus, Peter and John answered them, “Which is right in God’s eyes: to listen to you, or to him? You be the judges! As for us, we cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard” (Acts 4:19-20 NIV). The obvious advantage of a model for equipping the church that claims to be following the laws of God rather than man is that it bypasses all the friction of restrictive licenses and the resource expenditure (particularly in terms of time and money) that is inherent in the copyright system. (At least in the short term, and as long as the infringer is not caught and prosecuted.)

It is not hard to find “gray areas” in copyright law that can be leveraged to gain greater access to the intellectual property of others. This has led some to resort to “hacks” and clever manipulation of legal loopholes in order to circumvent the intent of publishers and exploit digital resources. “In some parts of the world outside the West,” we are told, “copyright means ‘right to copy.’”

While the hindrances experienced by the church are real and a decisive solution is urgently needed, implementing the “higher law” model to that end is both unwise and unhelpful. It is unwise because it is a misapplication of the principle suggested in the passage.[16] Furthermore, it erodes transparency, honesty, and forthrightness—all of which are important aspects of faithful ministry (2 Cor. 4:2) and should not be discarded for pragmatic reasons.

Even if this principle did apply in the context of biblical resources and copyright law, it is unhelpful because this model critically undercuts the ability of the church to work together as one—across all denominations and mission organizations—to meet the needs of the entire global church. It not only violates the God-given right of those who own the content, but it would likely pit Christian against Christian in legal battles, in a way that would bring discredit to the name of Christ (1 Cor. 6:6-7).[17] This is exactly the wrong way to resolve the problem and meet the need.

3.2. The Independent Model (“Reinventing the Wheel”)

In this model, the church in each people group creates their own biblical resources in their own languages with little or no reliance on existing resources. This “reinvent the wheel” model has the advantage of being highly contextual, with forms and structures of resources that are reflective of the culture and religious context in which they are designed.

The disadvantages of this approach are significant, however. Some people groups will languish for a long time before developing the capacity to recreate for themselves some of the most complex resources (e.g., a Hebrew Grammar). Furthermore, the quality, theological reliability, and technical interoperability of the resources across languages would likely be inconsistent.

3.3. The Dependent Model (Oversight by “Gatekeepers”)

Due in large part to the exhaustive (i.e., “all rights reserved”), automatic (i.e., transpiring at the point of creation) and enduring (i.e., lasts longer than a lifetime) nature of copyright law, the dependent model is the worldwide default. By virtue of creating the resource, copyright law establishes the creator as the owner (with a few exceptions) of the resource and, therefore, the gatekeeper who may (or may not) authorize use of the content by others. There are definite advantages to this model, particularly the order and tight control over the content (and all translations of it) that it affords the owner.

Furthermore, many content owners are generous when asked for permission to translate and use their content. But this model is built on several implicit assumptions that greatly hinder its effectiveness. For example, it is unrealistic to assume that any given content owner has the missional motivation or institutional capacity to provide translations of the content in more than a small fraction of the languages spoken by the global church. Consequently, the model implicitly assumes that everyone else who would benefit from a translation of the content in their own language…

- …can identify the copyright holder

- …shares a common language with which to ask them for permission

- …knows how to contact them and is able to do so

- …has adequate legal knowledge (e.g., how copyrights and licensing works)

- …has the ability to formulate a license request that accurately reflects their exact need

- …gets a response from the copyright holder (and it is in the affirmative)

- …understands the contract

- …has access to the counsel of an intellectual property rights attorney and sufficient financial resources to secure their services

- …is able to comply with all the terms and conditions of whatever license is granted, etc.

These are unrealistic expectations for the majority of situations, especially as meeting the need of the entire global church could require thousands of such processes happening concurrently with the same copyright holder. The generosity toward those who have overcome these hurdles and have received permission to translate provides no indication of the number who have not asked because the implicit assumptions are not true of them.[18]

The critical point to recognize is that regardless of the generosity of some content owners and the fact that it has worked reasonably well in some contexts, this model is intentionally designed to decrease availability of content. The whole point of reserving all rights for the content owner is so that everyone cannot redistribute it freely, and all requests for the content are funneled back to the content owner so that they may control (and optionally monetize) access to the content. This establishes a legally enforced dependency on the owner of the content for all access to and use of the content.

This model is well-suited for the purpose for which it was designed—providing a revenue stream from the content. But, due to the scope and degree of the legal restrictions that govern the use of the Bible and other biblical resources, the dependent model is misaligned with (if not diametrically opposed to) such missiological objectives as “eradicating Bible poverty” and “ending the spiritual famine of the global church.” The objective of providing everyone in the world with their own copy of the Bible and the resources to study it effectively, in their own language, as soon as possible, and at the lowest possible cost is in conflict with the de facto licensing model that limits the availability of these resources.[19]

An underlying skepticism regarding the need for open-licensed biblical content is sometimes voiced in the form of a question: “How much Bible translation and theological formation of the global church is actually being hindered by the ‘all rights reserved’ licensing policies that govern the use of most Bibles and biblical resources?” While this is an understandable question, it is based on the “argument from ignorance” fallacy (argumentum ad ignorantium, i.e. “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”). The conclusion (“Traditional licensing policies do not critically hinder the global church in any significant way”) is based primarily on the expectation (and perceived lack) of decisive evidence to the contrary. While there is considerable qualitative and anecdotal evidence that legal restrictions hinder the church in significant ways all over the world,[20] the absence of comprehensive or quantifiable evidence proving the severity and scope of the hindrance does not prove that the hindrance does not exist.

As ministry models are redesigned in light of biblical principles and the strategic opportunities God has given us today, unhindered progress can be made toward the alleviation of the spiritual impoverishment of the global church. The theological abundance that God has given the West will then no longer be only selectively shared with relatively few in the global south, but will be available without partiality to all.

3.4. The Interdependent Model (The “Open” World)

In the “open” world, the default answer to the question, “Can I do _____?” is always “Yes!”[21] In this model, biblical content is licensed in such a way that anyone who encounters it is already pre-cleared to use it, in accordance with the terms of the open license. This means that church leaders in a people group on the other side of the world who desire to translate a resource into their own language for use in equipping the saints for the work of ministry (Eph. 4:12) are already authorized to do so, with the full blessing of the content owner. They do not need to establish contact with the owner or negotiate terms and conditions for use of the resource, as the owner has voluntarily (and proactively) overcome all those hindrances by making the resource available under an open license.

In the “open” world, content can be shared in any format, on any device, by anyone, to anyone, online or offline. This not only exponentially increases the availability of the content (because anyone can also become a redistributor), it also avoids the expense and risk of accessing biblical content online (or in apps). In the “open” world, the Bible belongs to the church as its common property, with no strings attached.[22]

The open license under which biblical content is available tends to encourage collaboration and healthy interdependence across traditional boundaries of organizations and denominations. Church networks in India—many of whom have found it difficult to work together in the past—now have leaders working together to create improved translations of the Bible in their common languages. One of the factors they point to as instrumental in fostering this collaboration is the open license under which the Bible translation is being created and made available. By virtue of the fact that it is “locked open” no one entity can take it from the others and make it their proprietary, restricted content. This strongly predisposes collaboration by mitigating what might otherwise be a very real risk.

This release of restrictions not only increases the amount of content created but the variety of the content. The owner of a biblical resource intended primarily for believers in the West, for example, is unlikely to have the best sense of how the resource might need to be adapted for effective use in other cultures and languages. But leaders of church networks around the world usually do. Open-licensed biblical content can be adapted as needed by the church “on the ground” in every region in the world for effective use.[23]

The “open” world is not without disadvantages, however. First, it necessitates a quite different approach to traditional concepts of ownership and licensing. It requires that content owners consciously think through the implications of copyrights and licensing (a nontrivial undertaking) and then overcome every hindrance that would otherwise prevent them from proactively making their biblical content available under an open license.

In the “open” world things can also become less orderly, because the restrictions on distribution and reuse of content have been lifted. This results in an increased number of potential ‘pipelines’ of new content, none of which are directly controlled by the original content owner. Some, understandably concerned that the Word of God not be compromised and that doctrine not become corrupt, argue that the risk is too great and that it would be better to maintain tight control over Bible translations and biblical content, regardless of the inefficiencies and limited reach of this approach. This concern—that “bad things will happen to good content”—is one of several hindrances that prevent owners of biblical resources from making them available under open licenses. We will address each one in the next section.

4. The Hindrances to “Open” (and How to Overcome Them)

I have been a proponent of the “open” model for several years, and many objections to it have been raised. All of them are variations of six main hindrances, any of which may prevent the owner of a biblical resource from releasing it without restrictions for use by the global church. Each of these hindrances is addressed in this section.

- Fear of bad things happening to good content

- Reluctance to give sacrificially

- Content-dependent monetization models

- Incomplete missiology

- Confusing copyright and trademark

- Misunderstanding ‘open’ licenses

4.1. Fear of Bad Things Happening to Good Content

Setting aside this hindrance involves overcoming the fear that releasing some copyright restrictions on biblical content will result in malicious doctrinal distortion of the content.

Perhaps the most pervasive and effective obstacle preventing the release of biblical content under open licenses is the fear that doing so will make it possible for others to create derivatives that are doctrinally corrupt. This concern—that “bad things could happen to good content”—can be addressed from several perspectives but here we will focus on three: historical, practical and theological.

4.1.1. Historical Considerations

Elsewhere, I have considered the historical perspective and argued that attempts to protect the Word of God inevitably result in more harm than good (2015b:16). One example is the leaders of the institutional church in the 15th and 16th centuries who believed God had granted the Bible to their safekeeping as its stewards. But because of men like John Wycliffe, everyone could now have unrestricted access to it, unprotected. This caused no small sense of alarm, as it seemed that, without their protection of God’s Word and its interpretation, grave theological error was sure to follow. Henry Knighton (Chronicler of the Catholic Church) expressed the perceived danger posed by unhindered access to the Bible in no uncertain terms:

“Christ gave His Gospel to the clergy and the learned doctors of the Church… But this Master John Wycliffe… by thus translating the Bible, made it the property of the masses and common to all and more open to the laity… And so the pearl of the Gospel is thrown before swine and trodden underfoot…” (“Why Wycliffe Translated the Bible into English” 2014).

In order to “protect” the church from the bad doctrine that would surely ensue if the Bible was made too freely available, some ecclesiastical authorities sought to maintain their exclusive control of the Bible by fiat. Pope Pius IV issued such an edict:

“…if the Holy Bible… be indiscriminately allowed to everyone, the rashness of men will cause more evil than good to arise from it… bishops or inquisitors [may]… permit the reading of the Bible translated into the vulgar tongue… this permission must be had in writing… Regulars shall neither read nor purchase such Bibles without special license from their superiors” (Schaff 1908, emphasis added).

The similarity between this anti-Reformation papal edict and the licenses restricting the use of Bibles today is remarkable.

- Both are driven by the fear that bad things will happen if access to the Bible is not restricted.

- Both employ a policy of discrimination, where only those who are considered worthy by the ones in the position of controlling access to the content are granted permission to handle the Bible.

- Both establish “gatekeepers” in authority over the church who unilaterally grant permission (or not) to the church for how they can use the Bible.

- Both require the permission to be expressed in the form of a written license.

By contrast, the Reformers consistently and unanimously communicated the importance of “free and open” access by all people to the Word of God.

4.1.2. Practical Considerations

Before addressing this concern, we must first illuminate an implicit assumption held by those who have this concern: anyone who would make doctrinally-corrupt derivatives is law-abiding and submits to copyright law. If we are to assume people will honor the copyright-enforced terms and conditions of an “all rights reserved” license, then we must logically also assume they will honor the copyright-protected terms and conditions of an open license. This is important to clarify, because people who wish to damage the credibility of the Bible (or a publisher), cannot legally take a Bible translation that is made available under an open license, change some wording to distort critical doctrine, and make it available under the same branding, as though it were the original.[24] This is as illegal to do with an open-licensed translation as it is with an “all rights reserved” translation. If such a thing were to happen, the same legal mechanisms for righting such a wrong would be available to the copyright holder in either scenario.[25]

A variation on this concern is that cults might take the open-licensed translation, create their own derivative work by editing the translation in a few key verses to match their teachings and do so in far less time than would otherwise have been possible. While this may be legally permissible, there are other factors that suggest this may be quite unlikely to happen. In order to understand this, it is helpful to understand how the cults see the world in light of how open licenses work.

Not all cults create their own, doctrinally-slanted translations of the Bible. Some cults are intent on proving that they are legitimate Christians and so are highly resistant to creating their own doctrinally-adjusted translations, because this would delegitimize them as Christians. They use existing Bible translations (often preferring those that are hard to understand) and provide supplementary resources that interpret the Scriptures according to their own doctrines.[26]

Some cults do (mis)translate the Bible according to their own doctrines. They do so because they believe that others who call themselves “Christians” are corrupt in their doctrines and these corruptions are reflected in their Bible translations. In spite of fears to the contrary, this would strongly predispose cultic translators to not create a derivative of an existing Bible translation, even if it were available under an open license. Not only would the cultic translators be building on what they believe to be doctrinally corrupted texts, but the nature of the license itself would require them to indicate that the original (which they believe to be corrupt) is not only a legitimate translation but the foundation on which their own translation is built. That is, it would clearly indicate that the cult is a derivative of true Christianity, when they believe the exact opposite.

Specifically, if a Bible translation is made available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license (which we will consider in greater detail below), the creator of any derivative work based on it is legally required to forthrightly declare:

- That their work is a derivative, based on an original work (which implies authoritativeness).

- What they have changed in their derivative, as well as the reason for the change.

- The identity of the owner of the original work.

- That the original work is available at the location (e.g., a website) stipulated in the license by the owner of the original.[27]

To illustrate how unlikely this is to occur, consider the issue from the other direction. If the New World Translation, which unequivocally belongs to the Jehovah’s Witnesses and which is known to be deeply flawed theologically, were made available under an open license, would evangelicals use it as the basis to create a derivative translation, even if they fixed the doctrinal problems in it? It is most unlikely, because even though they could save years of time (compared to creating a completely new translation) their work would be forever tied to a doctrinally lethal original. They would be legally required to show that their derivative translation is “Based on an original work by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, available at www.jw.org, edited for doctrinal integrity.” Not only would this clearly attribute the New World Translation as authoritative, reputable, and worth building upon, but it would direct all readers of their derivative translation—both now and for the rest of time—to the website of those who teach false doctrine. This is, of course, highly unlikely. So, would it not also be equally unlikely going the other way?[28]

In summary, the fear that bad things will happen to good content if it is made available under an open license is usually rooted in three assumptions that seem alarming but, upon careful scrutiny, turn out to be more frightening than dangerous.[29] The first assumption is that restrictive “all rights reserved” licenses prevent bad things from happening to good content. As we shall see in detail below, copyright restrictions do not (and cannot) prevent bad things from happening to good content. The second assumption is that making content available under an open license makes it easier for cults (or malicious characters) to distort the content and deceive others by claiming it is the original. In reality, this is not permitted by open licenses any more than by restrictive licenses. Finally, it may seem that making content available under an open license makes it easier for cults or others who are opposed to the truth (but who purport to be its defenders) to perpetuate their error by granting them legal permission to create their own derivatives, in which they introduce theological distortions. While this is legally permitted, it is highly unlikely to occur, because they would be legally required to declare that their work builds on original work done by someone else—thus establishing someone whom they believe to be theologically deceived and whose work is doctrinally corrupt as the authoritative source. The same open license that permits the creation of the derivative work also requires that the truth be made known regarding the provenance and authoritativeness of the original.

As important as it is to understand these things, practical considerations alone do not adequately address this hindrance. At its heart is a fear that can only be overcome by an unshakeable confidence in the sovereignty of God in all things—particularly His self-sufficiency for the protection of His Word.

4.1.3. Theological Considerations

When one considers the ferocity of the hatred that Satan has for God’s people and God’s Word, and that God has faithfully protected both for over two millennia despite opposition of every conceivable form, the notion that God—who created the universe by His Word (Heb. 11:3) and who upholds it by the Word of His power (Heb. 1:3)—is dependent on copyright restrictions to prevent bad things from happening to His good Word is illogical.

God works all things according to the counsel of His good will (Eph. 1:11) and accomplishes every one of His purposes (Isa. 46:10-11). He sets absolute and non-negotiable limits on what Satan is allowed to do (Job 1:12; 2:6) and even those who oppose God are used by Him to accomplish whatever His hand and His plan have predestined to take place (Acts 4:27-28).

For his dominion is an everlasting dominion, and his kingdom is from generation to generation. All the inhabitants of the earth are counted as nothing, and he does what he wants with the army of heaven and the inhabitants of the earth. There is no one who can block his hand or say to him, “What have you done?” (Daniel 4:34–35 CSB, emphasis added)

Theologians throughout the centuries bear witness to God’s sovereign rule over all things.

God… foresees, purposes, and does all things according to His immutable, eternal, and infallible will. —Martin Luther (1525)

All events whatsoever are governed by the secret counsel of God. —John Calvin (1536)

Who is regulating affairs on this earth today—God, or the Devil? [The Scriptures] affirm, again and again, that God is on the throne of the universe; that the sceptre is in His hands; that He is directing all things “after the counsel of His own will.” They affirm… that God is ruling and reigning over all the works of His hands. They affirm that God is the “Almighty,” that His will is irreversible, that He is absolute Sovereign in every realm of all His vast dominions. —Arthur W. Pink (1949)

Scripture teaches that, as King, He orders and controls all things, human actions among them, in accordance with His own eternal purpose. —J.I. Packer (1961)

Given what the Scriptures say regarding the supremacy of God over all things, Buchanan is correct when he reminds us that our job is not to protect God or try to help Him take care of what is His own:

God is not safe. God is not a household deity, kept in our safekeeping. And—be warned—God’s safety is not our business. Our role on this earth… is not to keep the Almighty from mishap or embarrassment. He takes care of Himself (2009:30, emphasis added).

Regardless of reality, it may feel that making biblical content available under open licenses is risky. Piper observes that in some things, risk is unavoidable and (paraphrasing Dietrich Bonhoeffer) must be overcome in love:

The futility of finding a risk-free place to stand has paralyzed many of us… Risk is the only way forward… Risk avoidance may be more sinful—more unloving—than taking the risk in faith and love and making a wrong decision (2013:20-21, emphasis added).[30]

Piper goes on to observe that risk avoidance is often based on a false sense of security:

There is sometimes a subtle selfishness behind our avoidance of risk taking. There is a hypocrisy that lets us take risks every day for ourselves but paralyzes us from taking risks for others on the Calvary road of love. We are deluded and think that such risk may jeopardize a security that in fact does not even exist (22).

The Bible tells us of many who, believing in the sovereignty of God, risked everything on the proposition that God is sovereign, and all His purposes are good and invariably come to pass.

- Caleb voluntarily chose the mountains that had giants in them: “It may be that the LORD will be with me, and I shall drive them out just as the LORD said” (Joshua 14:6-10 CSB, emphasis added).

- Jonathan voluntarily went up against the Philistines with only his sword and his armor bearer: “It may be that the LORD will work for us, for nothing can hinder the LORD from saving by many or by few” (1 Samuel 14:6-7 CSB, emphasis added).

- David voluntarily went up against Goliath: “I come to you in the name of the LORD of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel… that all the earth may know that there is a God in Israel, and that all this assembly may know that the LORD saves not with sword and spear. For the battle is the LORD’s” (1 Samuel 17:45-47 CSB, emphasis added).[31]

None of these knew beforehand the outcome of their actions and each one was keenly aware of the risk involved. Making biblical content available in digital formats under an open license is also not without risk, as the author of a book about biblical principles for freedom from addictions observed:

When I released my book under an Attribution-ShareAlike License, I felt a little bit like Moses’ mother. Put your baby out there, and he will either be eaten by crocodiles or will save millions of people from slavery.[32]

The risk of bad things happening to good biblical content is real, regardless of the license. Copyright restrictions do not overcome this risk.

4.2. Reluctance to Give Sacrificially

Setting aside this hindrance involves loving the global church to the point of being willing to give generously and irrevocably for the building of the kingdom of God, even if someone else takes advantage of it by taking the credit or getting for free what they might have paid for.

The essential reason for making biblical content available under an open license is to proactively enable everyone to freely share in the benefit of the resource. It is a voluntary choice, motivated by love and compassion, that removes barriers to access, fosters equality across the entire body of Christ, and provides from the abundance of those who have to meet the needs of those who do not. It is a tangible application of the biblical principle of fairness in the church, taught by Paul to the Corinthians:

For I do not mean that others should be eased and you burdened, but that as a matter of fairness your abundance at the present time should supply their need, so that their abundance may supply your need, that there may be fairness. —2 Cor. 8:13-14 (CSB, emphasis added)[33]

This principle of voluntary giving by those who have in order to provide for those who do not has been part of the church from the beginning:

Now the entire group of those who believed were of one heart and mind, and no one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but instead they held everything in common… there was not a needy person among them because all those who owned lands or houses sold them, brought the proceeds of what was sold… this was then distributed to each person as any had need. —Acts 4:32–35 (CSB, emphasis added)

Generosity, by definition, requires a willingness to sacrifice for the good of others. Releasing biblical content under an open license for the good of the global church gives for free what might otherwise be sold for greater profit.[34] Doing so requires humility, because it makes it easier for others to take advantage of one’s generosity by increasing their own ministry. Here we look to the example of Paul in prison, who was taken advantage of by those who preached Christ out of “envy and rivalry… out of selfish ambition, not sincerely, thinking they will cause me trouble in my imprisonment” (Php. 1:15-18, CSB). Paul was not concerned that he was decreasing in name recognition and that others were gaining at his expense, because he remained focused on the true objective: “Whether from false motives or true, Christ is proclaimed, and in this I rejoice.” Paul cared more that the Kingdom of God advance, than that he be recognized as the one who advanced it.[35]

Paul’s attitude is reminiscent of John the Baptist (“He must increase, I must decrease” John 3:30), as well as Paul’s endorsement of Timothy who was not like others, because “they all seek their own interests, not those of Jesus Christ” (Php. 2:21). These examples of a selfless, humble, and “Christ-first” mindset stand in stark contrast to the attitude of some today, who evidently have the good of their commercial enterprise before the good of the global church, like this executive at a Christian publishing company:

The thought of releasing some of our biblical content under an open license makes me full of compassion for the poor man in Papua New Guinea who doesn’t have two nickels to rub together. But when I think of people who could afford to pay for it now able to get it for free, it gives me a rash.[36]

The point is not to suggest an obligation on the part of those who have biblical resources needed by the global church. As Peter told Ananias, “The property was yours to sell or not sell, as you wished. And after selling it, the money was also yours to give away (Acts 5:4 CSB).” Instead, the point is to show that if those who own biblical resources are willing to give sacrificially, those resources can be used to their fullest for the glory of God and the good of all His church.

4.3. Content-dependent Monetization Models

Setting aside this hindrance requires designing models of funding ministry that are not built on restricting the global church from access to and use of biblical resources, but that maximize freedom instead.

Before considering this topic, it is important to recognize at the outset that many (perhaps most) people for whom this topic of “content-dependent monetization models” applies are in this predicament innocently. Their intent was never to limit the availability of what they created—quite the opposite! They created it in order to bless and build up as many as possible with the insights God has given them. Thus it is with great respect for them and sincere appreciation for the work they have done that I attempt to address the dilemma in which they find themselves.

The new era of abundance ushered in by Gutenberg’s movable type printing press in the 15th century brought with it considerable financial risk. Printers (who traditionally printed low-risk content like Bibles and the writings of philosophers or celebrities like Luther) started to become publishers who would foot the cost of printing up front and make decisions about what to publish based on perceived economic viability of the work.[37] Over time, the model became standardized: authors create content, the publisher acquires the rights to the content from the author, then produces the content and markets it to their customer base. Because of their exclusive distribution rights (which eventually came to be enforced by copyright law), all revenues from the sale of access to the content go to the publisher and are divided with the author according to the terms of the contract.

The intent of this virtuous cycle—largely the same since the days of Gutenberg, and virtually identical whether in publishing or media production—is to incentivize the creation of content that people are willing to pay to consume. The model is also the default in the non-profit world of Christian ministry, even with “free of charge” biblical resources. Instead of direct sales of the content, however, the owner of the content (as the exclusive distributor) may receive donations from philanthropically-motivated benefactors who desire to extend the reach of the content. Effectively, the essential difference is who is paying to provide access to the content. This model is inherently neither unbiblical nor unethical, but it has unavoidable and consequential implications.

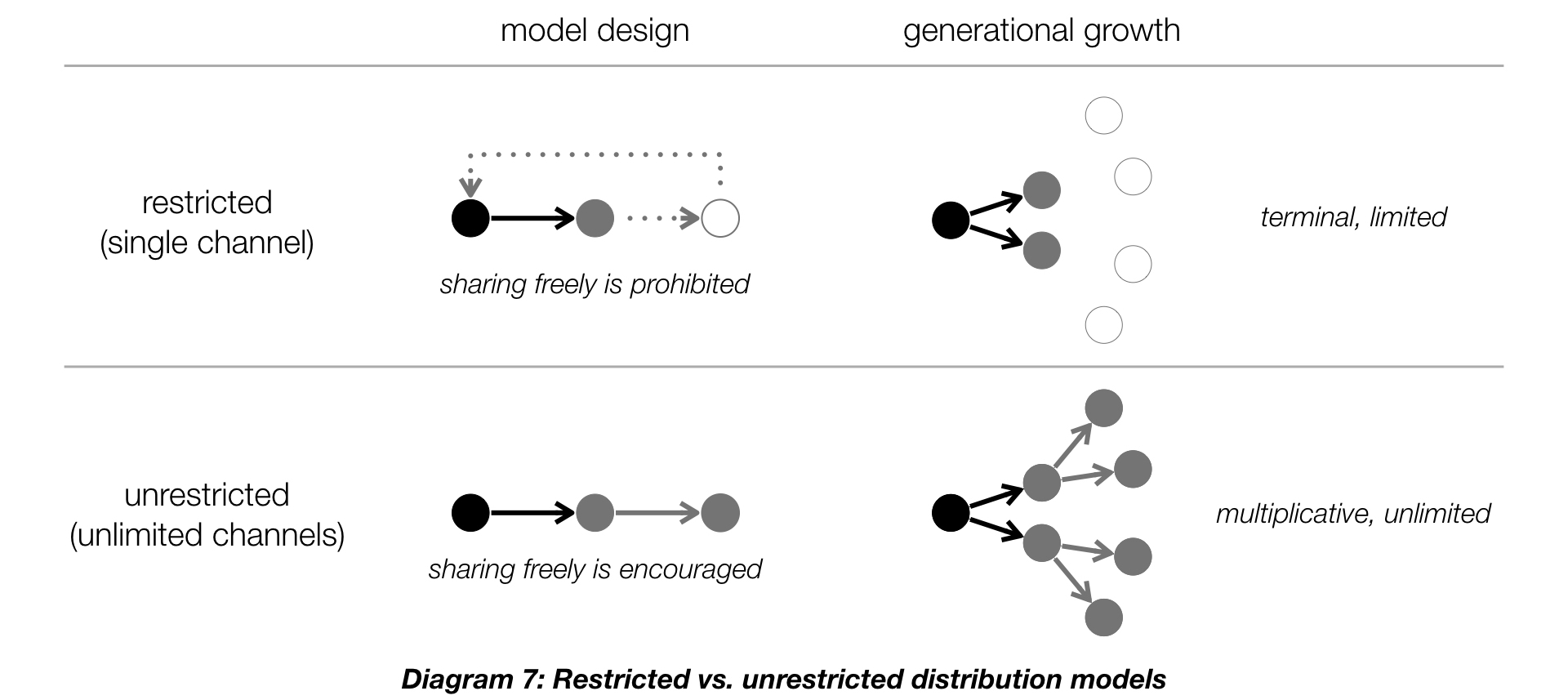

First, it decreases the availability of content. The model constrains the means of distribution to a single channel and reduces the reach of the content to the institutional capacity of the publisher. The use of a legal mechanism that is designed to decrease availability of content in order to increase profit is antithetical to the objective of making the content as broadly available as possible. Is it not counterproductive to fervently work toward “ending Bible poverty” by employing a licensing model that perpetuates scarcity?

Given that this model was not designed to make the content available in thousands of languages as swiftly as possible, but to maximize revenue from the relatively few languages where there is sufficient market to justify the investment of a translation, it decreases the usability of content by the global church. As we have seen, the right to use the content—including translation, adaptation, and revision—is reserved exclusively for the owner. Given the thousands of languages spoken by the global church and the effort required to translate and distribute a resource, this drastically limits the reach of the content. It is antithetical, therefore, to simultaneously state (or imply) that a biblical resource is of immense theological importance to Christians while simultaneously employing a licensing model that practically restricts its availability to those who speak a relatively small handful of languages. This may not be the intent of the owner of the content, but it is the default of the model itself: no one gets access to the content in a language they understand well unless the owner provides it for them.

Finally, this restrictive model conflicts with the abundance of the digital age. The new technologies of the digital era provide highly scalable models of content creation and distribution at vastly lower costs, but they cannot be effectively employed in a context of restrictions on biblical content. Increasingly, the global church has the technology and desire to provide biblical abundance in every language but is hindered by the lack of legal freedom.

In light of these limitations, it seems clear that the exclusive use of the “all rights reserved” monetization model constitutes an obstacle for the Gospel, as it hinders the global church from accessing and understanding the Word of God in every language. The apostle Paul recognized that “the worker is worthy of their wages” and that ministers who “sow spiritual things among you” have a rightful claim to “reap material things” (1 Cor. 9:11) as a result. But he also refused to claim this right if it became a hindrance:

Nevertheless, we have not made use of this right, but we endure anything rather than put an obstacle in the way of the gospel of Christ… What then is my reward? That in my preaching I may present the gospel free of charge, so as not to make full use of my right in the gospel. —1 Cor. 9:12, 18 (ESV, emphasis added)

Luther modeled the same pattern of “you received without paying; give without pay” (Matt. 10:8 ESV)[38]:

Luther received no income from his torrential publications because even though the publishers made a mint from them, Luther refused to take a penny, nor did he take money for all of his preaching. He simply wanted to spread the Word and trust God would provide (Metaxas 2017:353, emphasis added).

Today, there is an urgent need to adopt a similarly gracious mindset and collaborate in the creation of biblical resources that are unencumbered by monetization models that critically hinder the global church.[39] This is a known need, but too few in the church have yet understood the implications and helped bring it to pass.

It is high time that the Christian community awaken itself to the situation and dispatch a loud and strong cry in order to reclaim the biblical text from those who have made it into proprietary merchandise. It is not the “purity of the text” which has to be protected, but the liberation of that text from those non-church entities who desire to profit unjustly from marketing God’s word back to God’s people, who should own and control the dissemination of that word in the first place. Our ministry to a dying world requires sanctuary from the profit motive in regard to our sacred texts (Robinson 1996:13, emphasis added).[40]

As we shall see below, what is needed goes far beyond merely making biblical content available “free of charge.” It requires granting the entire global church—all of us—freedom to use the content in whatever way is needed, as though it belongs to us all, without a wall separating the “haves” from the “have nots.”

4.4. Incomplete Missiology

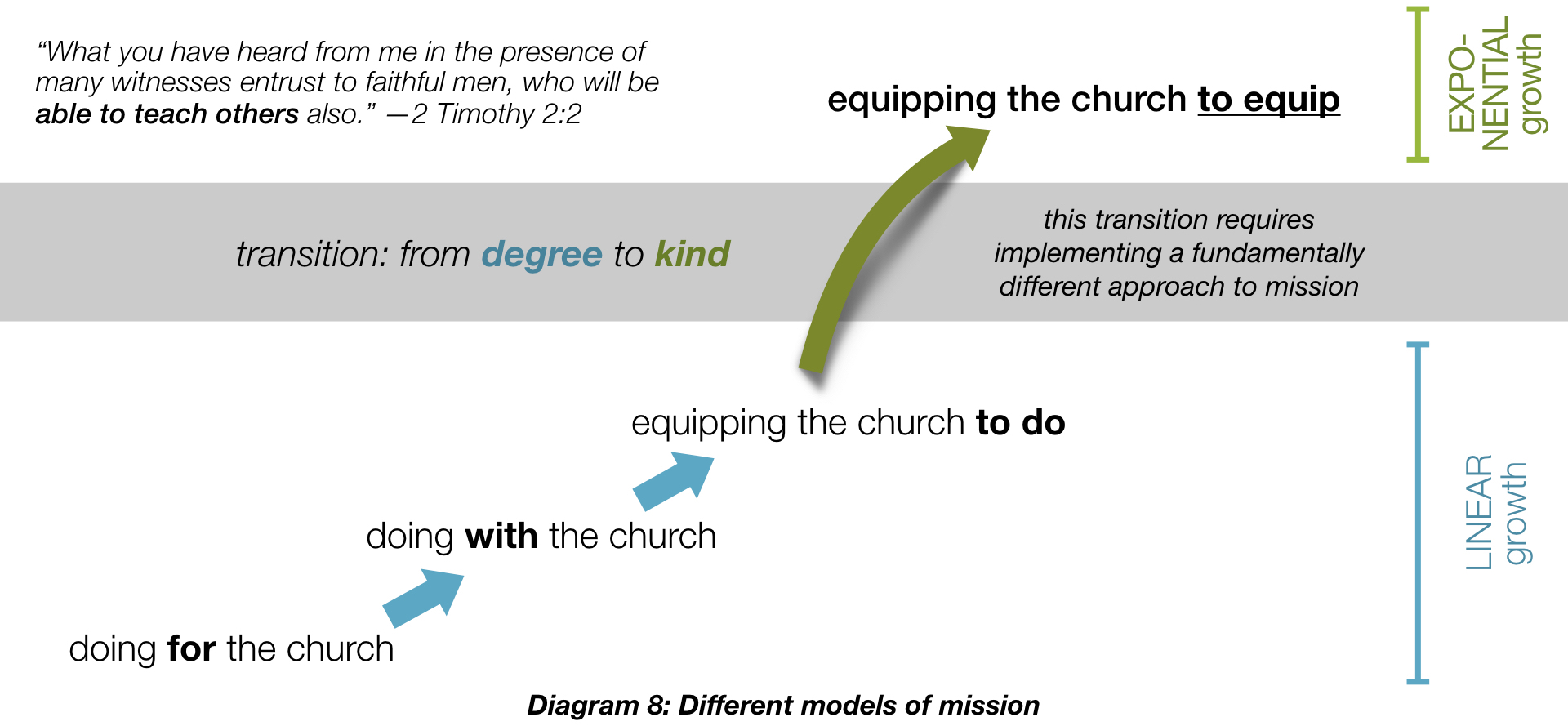

Setting aside this hindrance involves the implementation of a missiology that grants the rights to the global church to meet their own needs and equips the global church to not merely meet their own needs but to become equippers of others as well.

4.4.1. The Right to Meet the Needs

The emergence of the modern mission movement in the early nineteenth century cannot be understood apart from the rise of technocratic society.[41]

A technocratic society is one in which experts have the power and resources to solve problems and meet needs, as opposed to the people themselves.[42] Some patterns and strategies of missionary work since the early 19th century have (often unknowingly) been deeply influenced by their contemporary political contexts. The technocratic predisposition of such strategies has often resulted in outside “experts” maintaining the rights to control the church, sometimes until forced to leave the country by political opposition (e.g., China, Vietnam, some Middle Eastern countries).

This pattern is quite different from Paul’s model in the New Testament. He committed new churches to God’s care early (Acts 14:23), continued in relationship with the churches (1 Cor. 4:15; 1 Thess. 2:11), taught them as needed (Acts 20:17-35, every epistle), visited them when possible (1 Cor. 16:5), urged them in the right direction (Eph. 4:1; 1 Thess. 5:14), encouraged them to imitate the pattern of those who were faithful (Php. 3:17), but resisted leveraging the power of his apostleship to control them (2 Cor. 11:9; 1 Thess. 2:6-7). Banks observes:

Their freedom is a reality to be appropriated, not a possibility to which they must be gradually introduced. For this reason, his instructions to his converts are generally couched in terms of appeal and exhortation rather than command and decree (1994:181, emphasis added).

The contrast between missiological patterns that reflect technocratic, control-wielding predispositions and the model we see in the New Testament has been observed by many, including Roland Allen, in his critique of missionary strategies of the early 20th century:

If anyone suggests giving to the natives any freedom of action the first thought that arises in our minds is not one of eager interest to see how they will act, but one of anxious questioning; if we allow that, how shall we prevent some horrible disaster, how shall we avoid some danger, how shall we provide safeguards against some possible mistake? Our attitude in such cases is naturally negative (1927:112-113, emphasis added).

We rightly cringe at the paternalistic overtones in this statement. And yet, is it not this same fear—granting “freedom of action” to the global church—that motivates some owners of biblical content to use the fulcrum of copyright law and restrictive licenses as leverage over the church? Whether it is to protect their paradigm of ministry or to “safeguard” the Word of God against “horrible disaster,” “some danger,” and “possible mistake”, it is deceptively easy for owners of biblical content to inadvertently undermine the responsibility of the church in each people group and unwittingly perpetuate their spiritual malnourishment.[43] It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the continued undermining of the church’s responsibility, as evidenced by withholding from them the rights to provide themselves with the best theological resources, is fostering (or at least failing to prevent) widespread theological problems by creating a truth vacuum that is being filled by false teachers with doctrinal garbage (1 Tim. 4:1-2; 2 Tim. 4:3).

The solution to the problem of “Bible poverty”, however, is not for “experts” to develop a plan and build technologies that they then administrate on behalf of the global church, complete with custom licensing and governance structures. It does not involve building better mobile apps around an even bigger silo of restricted biblical resources, thus inadvertently blurring the lines between providing the Bible to the global church and presiding over their use of it.[44] Instead, it is for the entire global church to be irrevocably granted the legal rights—in terms of the unhindered freedom to make full use the best biblical texts and hermeneutical resources—to solve their own theological problems and meet their own Bible translation needs. It requires tearing down the wall of separation between “us” (the “haves”) and “them” (the “have nots”) by granting everyone the legal right to “have”, without exception.

4.4.2. Equipping to Equip

There are several models that can be used to accomplish a missional objective (e.g., translating the Bible, developing an evangelistic strategy, training leaders, etc.). One could do it for the church, with the church, or equip the church to do it for themselves. This progression increases in effectiveness, but it remains linear in scale. It is only when a model crosses the line to the decisively different model of equipping others to equip others that a compounding, non-linear growth process becomes possible.

This is one of the central aspects of the pattern we see in the New Testament, particularly with regard to how Paul approached the task of accomplishing the Great Commission:

What you have heard from me in the presence of many witnesses, commit to faithful men who will be able to teach others also. —2 Tim. 2:2 CSB[45]

The licensing of biblical content is of critical importance in this progression, because “all rights reserved” licenses tend to create a centralized model that only scales in a linear progression. If each and every element of the global church that desires to translate, adapt, or redistribute a resource must be granted explicit permission by the owner of the resource, the friction in the process inevitably slows it to a crawl, despite all good intent to the contrary.

By contrast, open-licensed resources lead to a decentralized model that can scale in a non-linear progression by removing all legal friction from the process. Anyone who needs to use the content in any way for the building up of the church is pre-cleared do so immediately, subject to the conditions of the license. This enables the entire church to collaborate together in the translation, redistribution, and use of the content, in whatever way needed, without hindrance.

4.5. Confusing Copyright and Trademark

Setting aside this hindrance involves understanding how copyright law works and how it differs from other branches of intellectual property law, namely trademark.

One of the most common concerns about making biblical content available under open licenses is articulated in this statement by a well-known American pastor:

…You don’t want anybody taking… the ESV, and then changing the words to wrong translations. The safeguard we have in our culture to prevent such distortion is to copyright things. If you want to produce another translation of the Bible you have to call it something else. You can’t call it the ESV, NIV, RSV, or NASB. You have to call it your own thing, so people know that you’re taking responsibility (emphasis added).

The conclusion that “copyrights (i.e. ‘all rights reserved’ licenses) protect against distortion by others” is founded on several false assumptions in this statement.

Assumption 1: “Anybody” can take the ESV and change the words – Even if the ESV were made available under an open license, the only way others could actually change the ESV itself would be if they had access to the publishing process such that they could publish an updated version that contains the distortions. This has nothing to do with licensing and everything to do with the editorial team and the process of publishing an updated text.

Assumption 2: If they create a distorted derivative, it will be indistinguishable from the ESV – As we saw above, if any Bible is made available under an open license, the most that other parties could do would be to create their own derivative based on it that includes their changes in their own copy. But they would be legally obligated to change the name, indicate the provenance of the original, that they have made their own modifications, and what those modifications are.

Assumption 3: Copyright actually safeguards against distortions – In an age when all content is digital, and anyone can effectively do whatever they want with content on any computing device to which they have access, introducing distortions into copies of original content is much easier to do. Copyrights cannot and do not prevent distortion. They merely provide the owner of the copyright with a legal platform from which to sue infringers, and then only after the fact. The fear of a lawsuit may, in some situations, be a deterrent.[46] But apart from the irony of attempting to build a missional movement on the implicit threat of a lawsuit by Christians who assert they are defending the Word of the sovereign God, this line of reasoning is overly optimistic. Just because a copyright owner does not know of bad things happening to their copyrighted content does not mean they are not happening—especially if the content is in high demand! Every owner of digital content in the Internet age should assume their copyright-restricted content is being used in all kinds of ways of which they would not approve—if they knew about it. The people who really are hindered by the “all rights reserved” are those who understand what it means, fear God, and desire to do what is right.

Assumption 4: Copyright is the best legal tool to use – It is important that if someone creates a derivative of any open-licensed Bible that they “call it something else… call it [their] own thing, so that people know [they] are taking responsibility.” But this speaks to the identity of the derivative and the one who created it—and identity is not the point of copyright. Copyright law grants the creator of an original work exclusive rights for its use and distribution.

Trademark is the branch of intellectual property law that deals with identity. The United States Patent and Trademark Office defines trademark as:

a word, phrase, symbol, or design, or a combination thereof, that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others.

In 1836, Cotton Smith, the president of the American Bible Society remarked in his address at the Annual Meeting of the Society:

The Society is charged with the preservation, not only of the truths of the English Bible but of its precise language… An interdenominational Society only can properly secure the text against alteration; it being a body trusted by all denominations, it watches over the inviolability of the text. A copy bearing the imprint of such a Society is of guaranteed authenticity.[47]

This suggests that imprints—which identify the publisher—were the means by which the early Bible societies watched over “the inviolability of the text” and ensured that it was of “guaranteed authenticity.” The first known use of copyright to “insure purity of the text” (according to the statement on the copyright page) came many decades later, when the New Testament of the American Standard Version was published in 1901.[48]

All of this suggests that there is widespread and historical agreement regarding the need to preserve and clarify the identity of who has done the work—both in terms of original works, and for derivative works created from them.[49] In recent history, publishers have used copyright law combined with restrictive licenses to forbid all uses of content without their explicit approval. The use of a different branch of intellectual property law—trademark law—may provide an effective and less stifling framework for ensuring that the identity (and consequently, the reputation) of the creator of a work is always clear. We will consider this in more detail later.

4.6. Misunderstanding “Open” Licenses

Setting aside this hindrance involves not only understanding what an “open” license is, but also understanding what it is not and what it does not imply.

4.6.1. What “Open” Means

With regard to the licensing of content, the term “open” means:

Anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness).[50]

The specific freedoms contained in this concise definition can be summarized by the “5 Rs” of freedom:

- Retain – The right to make, own, and control copies of the content (e.g., download, duplicate, store, and manage).

- Reuse – The right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video).

- Revise – The right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language).

- Remix – The right to combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup, or to repurpose it for another use).

- Redistribute – The right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend).[51]

An open license is necessarily irrevocable, granting the stated freedoms perpetually. This is critically important, as these freedoms are not merely addressing distribution of finished content. They are intended to create a stable foundation for creation of other resources from them. An unstoppable movement of interlinked and interdependent biblical content in every language must necessarily be built on a foundation that can never be shifted or removed.

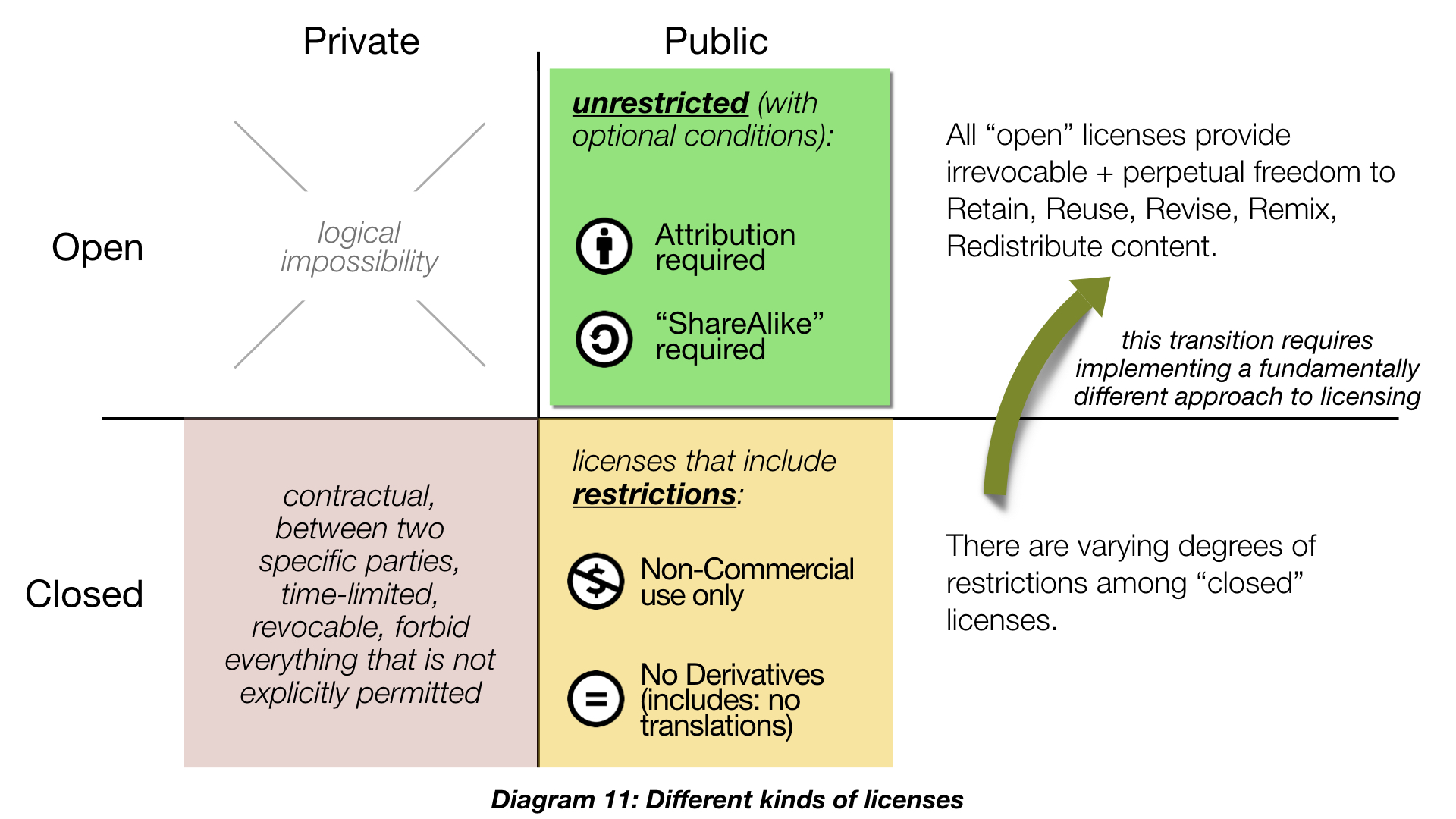

4.6.2. Creative Commons: Globally-effective, Standardized Licenses

Creative Commons is a non-profit organization that provides royalty-free public licenses that make it easy to release restrictions on content, subject to certain conditions. They are designed to be internationally valid—essentially jurisdiction-neutral while remaining effective globally.[52] This makes it possible to easily and legally combine and remix content across languages and domains using standardized licenses. Not all the licenses they provide constitute “open” licenses, however.[53] There are only two Creative Commons licenses that qualify as open licenses:

- Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) – this license waives all rights other than the preservation of the provenance of the original (Attribution).

- Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) – this license waives all rights other than the preservation of the provenance of the original (Attribution) and the perpetuation of openness in derivatives (ShareAlike).

In addition to these two licenses, Creative Commons provides a tool to dedicate a work to the public domain:

- Creative Commons Zero (CC0) – this waives all rights, effectively making the content equivalent to the public domain (PD).

Creative Commons licenses are irrevocable and perpetual, but they terminate automatically if the conditions are violated.[54]

It is important to understand that “Creative Commons license” is not a synonym for “open license”. Some people mistakenly use a phrase like “release under a Creative Commons license” to mean “release under an open license.” These do not mean the same thing! There are six Creative Commons licenses, and only two of them are “open” licenses (CC BY and CC BY-SA). The other four all include restrictions that limit how a work can be used, thus failing to meet the industry standard definition for an “open” license, as explained above. The diagram below contrasts “Creative Commons licenses” with “open licenses.”

4.6.3. What “Open-licensed” Does Not Mean

Understanding what “open-licensed” means is important, but it is also necessary to understand what it does not mean, particularly with regard to ownership, derivative works, quality control, and monetization of the content.

Regarding Ownership

- “Open-licensed” does not mean “copyright free” or “in the public domain.” When the term of copyright protection expires, a resource enters the public domain, where copyright restrictions no longer apply. An open license is not the same thing as the public domain! The open license defines the freedoms granted to others by the owner of the content but does not transfer the content to the public domain or nullify ownership of the content.[55]

- “Open-licensed” does not mean “copyright assignment”. An open license does not transfer the rights in the content to anyone else—it merely states what freedoms others have with regard to the use of the content. This is why open-licensed resources generally include the copyright statement (who owns the rights to the resource) and the license statement (what others are pre-authorized to do with the content under the terms of the license).

Regarding Derivatives

- “Open-licensed” does not mean others are free to change the original. Releasing content under an open license does not make it editable by others, nor does it mean that someone can change a copy of the content and say that it is the original. This is explicitly forbidden by open licenses, and it effectively does not happen: there is always a way to identify derivatives.

- “Open-licensed” does not mean that the owner of the original has responsibility for or endorsement of derivatives created from it. Open licenses do not permit others to do something with a copy of the content and suggest that the owner of the original approves of it. The owner of the original is never liable for what others do with their copy of the content—the one who does the work bears that responsibility alone.[56]

Regarding Quality

- “Open-licensed” does not mean “open workflow” or that the content is created using a crowd-sourced, open process (e.g., Wikipedia) where anyone can make changes to the content. The means by which the content is created has nothing to do with the license under which the content is made available for others to use.

- “Open-licensed” does not mean low quality. The value and trustworthiness of the content is intrinsic to the content itself (and possibly suggested by the identity of the creator) and has nothing to do with the license under which the content is made available.[57]

Regarding Money

- “Open-licensed” does not mean “free to download” (and, conversely, “free to download” does not mean “open-licensed.”) Making content available free-of-charge is an important first step to equipping the entire global church, but it does not address freedom to translate, adapt, build on, redistribute, and use as desired.

- “Open-licensed” does not mean “not for sale”. Open-licensed resources absolutely can be sold for profit. The open nature of the license merely prevents the use of monopoly to contrive an artificial scarcity of the resource so as to drive up the price. This simultaneously ensures that digital versions of the resource can always be (and inevitably are) made freely available, while also incentivizing anyone who with the means to do so to legally make the resource available in physical formats (e.g., printed books, MicroSD cards) at fair prices.

4.6.4. From “Private + Closed” to “Public + Open”

When a content owner licenses their content for others to use, they need to address two distinct aspects of licensing. First, they need to address the scope of the license, whether it is “public” or “private”.

- Private licenses are contractual in nature, made between two parties, and are usually term-limited, defaulting back to “all rights reserved” after the term expires, and until a renewal is signed.

- Public licenses are licenses where the owner of the content grants pre-approved and perpetual permission for use of the content by anyone who encounters the content by any means and at any time in the future, provided they comply with the terms and conditions of the license.

Second, they need to determine whether the license will be “closed” or “open”.

- Closed licenses include restrictions that specifically disallow some uses of the content, notably the creation of derivatives and the use of commercial means to extend the reach of the content. (Examples included Creative Commons licenses that contain “NoDerivs” or “NonCommercial” clauses, respectively).

- Open licenses are always public licenses, and they do not hinder how the content is used, with the optional conditions of preserving the source and identity of the original, and perpetuating the openness of derivatives.

Within the realm of biblical content, virtually all licenses today are “private” and “closed” (in the lower left quadrant of this diagram):

Often, when an owner of biblical content desires to make it more broadly available, they try to “go open” by means of a contractual, private license (the top left quadrant), which is a logical impossibility—intrinsically, a private license cannot be an open license. So, in an effort to prevent distortion of the content and disallow someone else from monetizing it, they may make the jump to a “public license” that disallows the creation of derivatives or use of commercial means to extend the distribution (the lower right quadrant). These restrictions are understandable, but they are problematic for the global church. The whole point of releasing “theological building blocks” under an open license is so that the global church can create derivatives from them. Furthermore, the notion that “free means free” (and therefore warrants the use of a “non-commercial use only” restriction) is short-sighted and unnecessarily hinders the reach and usefulness of the content. (This will be addressed in more detail below.)

The essential step for the content owner to take is from “closed” to “open” by releasing their content under a truly open license, for the glory of God and the good of His church (top right quadrant). Here, the global church is able to participate with equality in the translation and adaptation of the content for effective use in every people group and language that desires it.

5. What the Future Could Look Like

In short, the future could look remarkably like the past. About 400 years before the first known use of copyright to restrict access to a Bible translation, a German monk named Martin Luther accidentally changed the course of history. Luther’s pamphlets and books could not be restricted by copyright law, because that would not be invented for another two centuries.[58] The success of the Reformation—the rapid spread of ideas that changed the world forever—was accelerated by the “free and open” nature of the publishing environment of that time.

Of course, in this new era of printing, before there were copyright laws, a single copy [of Luther’s writings] could quickly beget others—which begat others, which begat others—and before anyone knew it, they would be fanning out across the landscape like Abraham’s descendants and would become as numerous as the stars in the heavens (Metaxas 2017:126, emphasis added).

The way the information contained in Luther’s writings spread through the decentralized network of publishers, consumers, and (re)distributors of his day is remarkably similar to the networked world of today.[59]

The media environment that Luther had shown himself so adept at managing had much in common with today’s online ecosystem of blogs, social networks and discussion threads. It was a decentralised system whose participants took care of distribution… Luther would pass the text of a new pamphlet to a friendly printer (no money changed hands) and then wait for it to ripple through the network of printing centres across Germany… Copies of the initial edition, which cost about the same as a chicken, would first spread throughout the town where it was printed. Luther’s sympathisers recommended it to their friends. Booksellers promoted it and itinerant colporteurs hawked it. Traveling merchants, traders and preachers would then carry copies to other towns, and if they sparked sufficient interest, local printers would quickly produce their own editions… A popular pamphlet would thus spread quickly without its author’s involvement (The Economist 2011, emphasis added).[60]