Who owns the Bible? By “the Bible,” I’m not speaking of the English translation you might typically use; I’m speaking of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament. Even then, the question may not be clear because the text of the Bible comes to us in different stages.

- Autographs of Scripture are the original writings of the prophets and apostles.

- Apographs of Scripture are copies of autographs; in an ancient context, these are manuscripts (MSS) written by copyists.

- Digitizations of manuscripts of Scripture are digital photographic reproductions that capture the text in a way that is easily shareable and may be studied by multiple scholars at once or even made accessible to the public.

- Critical texts of Scripture are recensions of manuscripts into a single text in an attempt to reconstruct the original writings.

Since the autographs of Scripture are generally regarded as nonextant (no longer existing), any debate over their ownership can only be theoretical. However, the question of ownership remains for apographs, digitizations, and critical texts.

We will answer this question by way of survey, considering the landscape of claims made on manuscripts, digitizations, and critical texts. Afterward, we will consider who should be regarded as the owner of each. While often considered critical to the reconstruction of the original text, we will not address ancient translations of Scripture such as the Septuagint (LXX) or the Peshitta.

Physical Manuscripts

Before the invention of the printing press, the Bible was hand-copied in manuscripts: the word “manuscript” literally meaning “hand writing.” Many of these have been preserved or rediscovered, and are possessed by public authorities or various private collections.

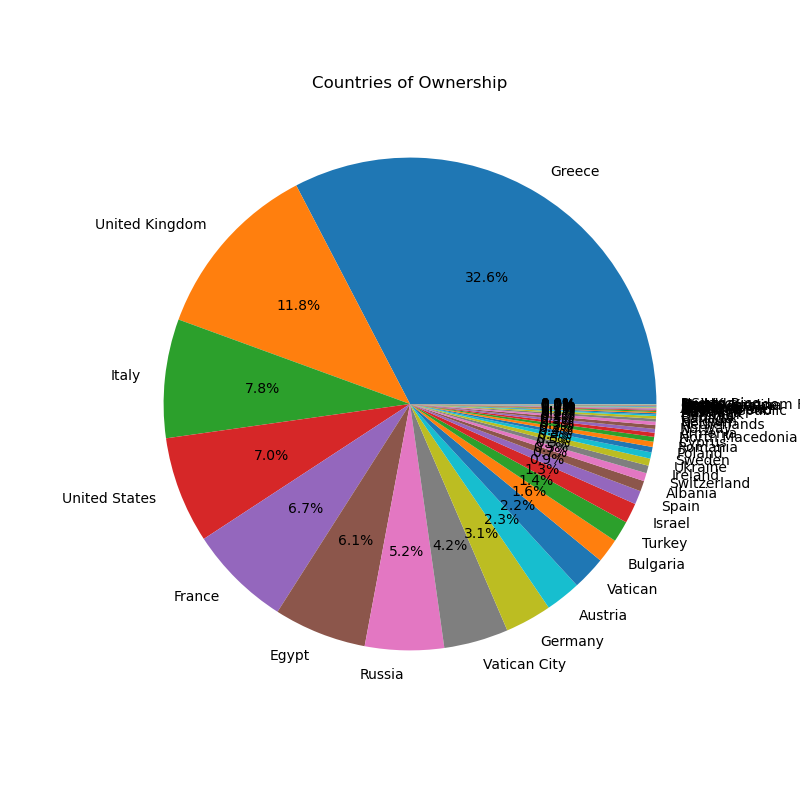

Given the quantity of manuscripts and artifacts containing Scripture, just determining the matter by count is unhelpful. For example, using the fairly exhaustive catalogue available on Wikipedia, we could visualize the ownership by country in a pie chart.[1]

Countries of Ownership for NT MSS and Artifacts

Instead, it is best to assess the matter by focusing on the most significant manuscripts used by scholars.

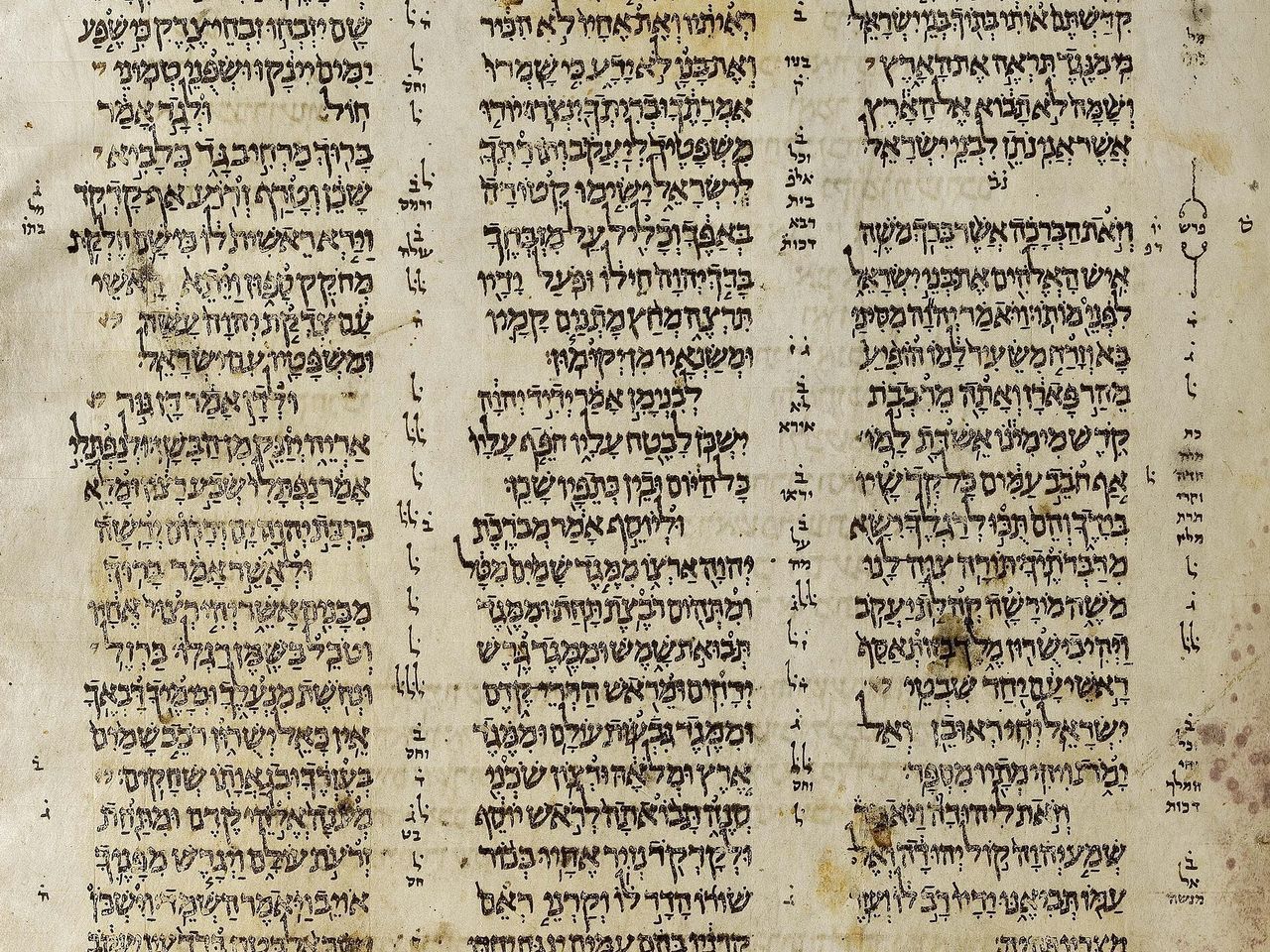

Old Testament Manuscripts

The Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) are the oldest existing collection of OT MSS. Primarily gathered between 1946 and 1956, these were housed in what was then called the Palestine Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem. After the six-day war in 1967, Israel gained control of the museum and consequently the DSS. Almost all of these scrolls now exist in the Shrine of the Book in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. While the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) is now in control of the DSS, because of the timing of the discovery and the nature of their acquisition, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority dispute this claim.[2]

The two primary manuscript codices of the Old Testament are the Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad Codex. The former is owned by the State of Israel and kept in the Israel Museum along with the DSS. The latter is owned by Russia and housed in the National Library of Russia in Saint Petersburg.

Many other Hebrew manuscripts exist in public collections in London, Oxford, and elsewhere. Private collections also exist, one of the largest being the Museum Collection in Washington, D.C., which is owned by Hobby Lobby.

New Testament Manuscripts

The Papyri of the New Testament are owned by various public and private institutions. The more notable ones include the John Rylands University Library in Manchester, the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, and the Bodmer Library in Cologny, Switzerland.

The two primary codices are Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus. The former is owned by the British Library in London. The latter is owned by the Vatican and housed in the Vatican Library.

Manuscript Digitizations

A number of technologies developed between the era of hand-written manuscripts and digital photography, not limited to the printing press and film photography. Regardless, artifacts from earlier eras of copying are relatively unimportant for our purposes. The wealth of manuscripts and their subsequent preservation is so great that artifacts from these intermediary methods—printed books, film reproductions, etc.—are not worth our consideration here. Rather, we may skip ahead to the state of the art reproductions captured through digital photography.

So who owns the digitizations of the manuscripts of Scripture?

Hebrew Old Testament Digitizations

When the DSS were acquired by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), they maintained a policy of keeping the scrolls unreleased until research could be completed on them, including the construction of whole texts from fragments. However, this research dragged on for years, until by the 90s, less than 50% of the scrolls had been published. The remaining scrolls had been photographed and kept for safekeeping in various places, including the Huntington Library in California. Herschel Shanks—the founder of a Biblical Archaeology magazine—had access and released the facsimiles. Though he was successfully sued for this, it put a dent in the monopoly on access.[3]

In more recent years, the DSS have become more accessible through partnerships between controlling authorities and Google. Along with the IAA, Google developed the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.[4] This digital archive contains a standard copyright statement:

“All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced, displayed, modified or distributed in any form, with the exception of single copies for private use, without the express prior written permission of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and in compliance with the stipulated terms of use. For information on licensing content from this site, please contact us.”[5]

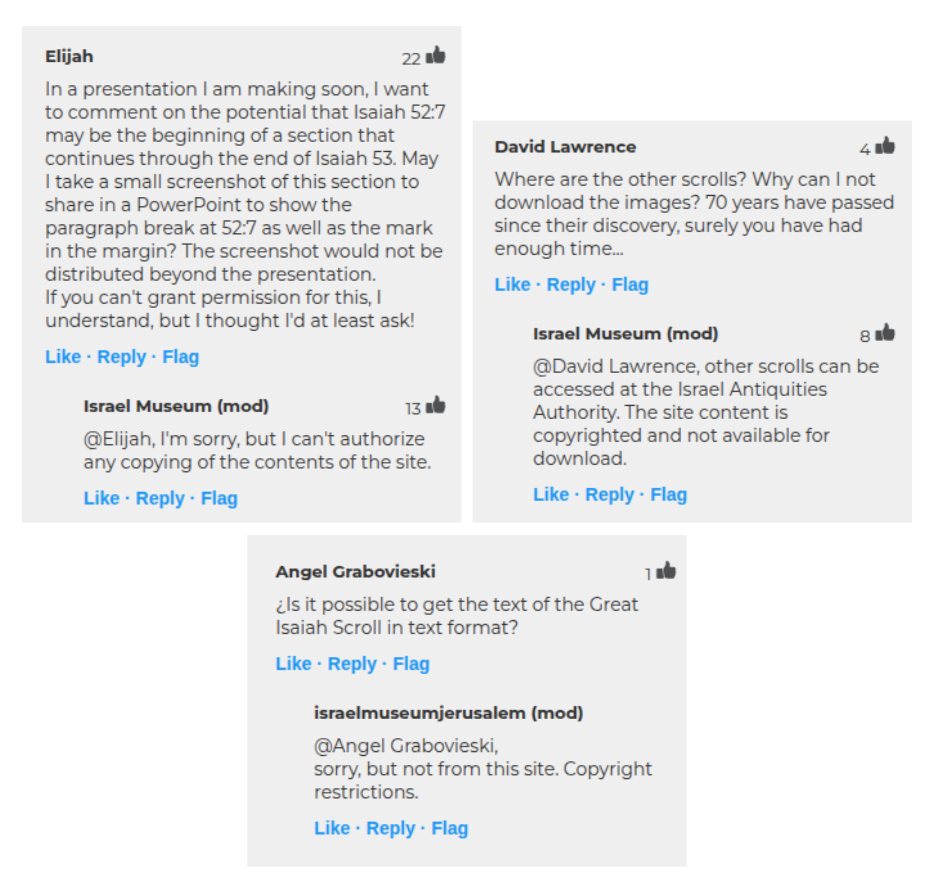

A complementary set of DSS digitizations were published by Google and the Israel Museum in the Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Project,[6] which contains a number of significant MSS like The Great Isaiah Scroll. The copyright page includes this straightforward prohibition on use:

“Copyright in the digital images of the manuscripts, created by the Israel Museum and displayed on this site, is held by the Israel Museum. Reproducing these digital images in any manner other than for research or private study requires prior permission or licensing.”[7]

Additionally, the website contains some comment interactions from the museum reasserting these restrictions.[8]

Both of these sites use viewing widgets that make the images difficult to download, although screenshotting cannot be prevented and a clever web user could figure out how to fetch the assets and stitch the images together.

Masoretic manuscripts remain a bit more accessible, although photographers and museums likewise assert copyright on their digitizations. For example, the color scans of the Leningrad Codex appear with “© Bruce E. Zuckerman” on every page.[9] The Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem claims copyright on the best digitizations of the Aleppo Codex, photographed by Ardon Bar Harma in 2002.[10] The Bodleian library has a number of Hebrew manuscripts they have made available online, asserting a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license on each.[11] The British Library also has a large collection of digitized MSS under the same terms,[12] although the original page that collated these is no longer available.[13] The Cambridge University Library (CUL) has collections that include notable OT MSS.[14] Unlike other sites, the CUL’s viewer widget offers a downloading feature, but still warns that the library owns the copyright and republication requires express permission.[15]

Some of these manuscripts and others are available through the National Library of Israel’s Ktiv project. Each collection has its own terms of use, but prohibition of any copying without permission is typical.[16]

Greek New Testament Digitizations

The Codex Sinaiticus Project has digitized Codex Sinaiticus (א). According to the website, “This electronic version of Codex Sinaiticus is provided only for non-commercial personal and educational use, by the British Library, Leipzig University Library, St Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai and the National Library of Russia.”[17] It goes on to clarify, distinguishing between the physical asset and electronic copy:

The original item itself is in the public domain in most jurisdictions and therefore not protected by copyright under applicable laws. However rights in the electronic copy and certain associated metadata are owned by the holding institutions. If you wish to make use of this electronic copy or its metadata other than for non-commercial personal or educational use, you must first obtain the written permission of the relevant institution.[18]

The Vatican Library (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana) publishes images of Codex Vaticanus (B).[19] These are all displayed with an imposing “ALL RIGHTS RESERVED” watermark, and the metadata contains the following notice: “Free use of this image is only for personal use or study purposes. Rights must be requested for any use in printed or online publications.”

The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM) run by Daniel B. Wallace has the largest collection of NT MS digitizations, many of their own production, some being sourced from other collections.[20] CSNTM requires explicit permission be granted for any and all use of material found on the site. Interestingly, their published terms of use include not only assertion of copyright, but also a justification for this assertion and threat of litigation for those who would fail to comply.

Current U.S. copyright law protects any and all works produced by any individual or institution at the moment of production, whether published or unpublished. Therefore, all material produced by CSNTM (defined as including all original works of creative, expressive and/or intellectual works without limitation to texts, pictures, graphics, movies, audiovisual pieces, sound recordings, photographs, images, website content, et al) is under copyright protection.

…

CSNTM may bring legal action against such offenses. These proceedings would seek, but are not limited to, injunctions to stop the usage of CSNTM copyrighted material and, if necessary, monetary damages (including court costs) from the offender.[21]

The Cambridge University Library has a number of NT MSS available as CC BY-NC,[22] and the British Library has some labeled as being in the public domain or being in the public domain outside of the UK.[23]

Critical Texts

Manuscripts are collated and then rescinded into critical texts. Variations between different manuscripts—spellings, word order, omissions, inclusions—are all weighed to make a judgment on the likely shape of the original text. These are often published alongside a critical apparatus, records of textual variants, often presented as footnotes to the critical text.

While similar to critical texts, diplomatic editions of Scripture do not seek to reconstruct the original texts, but uncritically reproduce a single manuscript. These are often published alongside a critical apparatus.

Hebrew Old Testament Diplomatic and Critical Texts

The German Bible Society publishes the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), which is a scholarly edition of the Leningrad Codex containing a critical apparatus.[24] The Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ), still incomplete, is the fifth edition in this series, drawing from a wider range of sources.[25] The former is accessible online while the latter is not. In either case, the German Bible Society (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart) claims copyright.

The Open Scriptures Hebrew Bible (OSHB, sometimes OHB) is a text based on the Westminster Leningrad Codex.[26] The text itself is public domain, although the lemma and morphology data are available under a Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY). Similarly, the Open Hebrew Bible is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license (CC BY-NC).[27]

On the other hand, the Hebrew University Bible Project (HUBP) is designed to reproduce the Aleppo Codex along with a critical apparatus.[28] This work is incomplete, but what exists is copyrighted by HUBP.[29]

The Hebrew Bible: A Critical Edition (HBCE)—formerly known as the Oxford Hebrew Bible (OHB)—is another incomplete critical text that attempts to restore the original text.[30] Copyright is held by SBL press.[31]

Greek New Testament Critical Texts

Among those critical editions that employ an eclectic methodology, the Nestle-Aland (NA) and United Bible Societies (UBS) editions of the New Testament are identical in text, while the former contains a more extensive critical apparatus. This text is available online, but the German Bible Society (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart) holds the copyright. Similarly, the Tyndale House Greek New Testament (THGNT)[32] may be accessed online, but Tyndale House holds the copyright.[33] The Society of Biblical Literature’s Greek New Testament (SBLGNT) is available under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY).[34]

Older eclectic critical editions are available in the public domain by virtue of their age. These include the Nestle 1904 edition[35] as well as the 1881 Westcott-Hort (WH) text.[36]

Even older textual traditions likewise exist in the public domain by virtue of age. These include the 1550 Stephanus Textus Receptus (TR),[37] Schrivener’s TR,[38] and Tischendorf’s Greek New Testament.[39]

Maurice A. Robinson and William G. Pierpont published a Majority Text version of the New Testament first in 1979. While a copyright notice is presented at the opening of the book, the custom dedication releases it into the public domain.[40]

Using all of the above with a base of the Nestle 1904, the Berean Standard Bible has published an interlinear Bible,[41] dedicated to the public domain.[42]

The Questionable Legitimacy of Copyright Claims on Digitizations and Critical Texts

Despite all these claims to copyright, there is a significant reason to doubt them all: Most jurisdictions reject sweat of the brow doctrine.

Sweat of the brow—named after the idiom of Genesis 3:19—is a copyright doctrine that regards labor as sufficient grounds for copyright. For example, is a listing of facts, like a telephone book, subject to copyright? In a sweat of the brow jurisdiction, the answer would be “yes,” in a non-sweat of the brow jurisdiction, the answer would be “no”. In fact, the court case that most clearly established the US rejection of this doctrine centered around this very issue: Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service.[43] It doesn’t matter how much labor someone puts into a work, for copyright to be applicable, it must be an original work, having “at least a modicum of creativity.” The purpose of copyright in its legal definitions is, after all, to promote creativity, not to reward labor.

The United Kingdom has likewise abandoned using skill and labor as criteria for determining copyright infringement.[44] Much of this had to do with their membership in the EU. For example, the EU has a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market that states that reproductions of works of visual art that are in the public domain cannot be subject to copyright or related rights. This rejection of sweat of the brow doctrine has been upheld in a post-Brexit UK with THJ v. Sheridan.

Israel likewise has no sweat of the brow doctrine, but the bar for originality is minimal. In Qimron v. Shanks the Israeli Supreme Court upheld copyright on a reconstructed Dead Sea Scrolls text.[45] Operating in the US, Hershchel Shanks released a reconstructed text and was successfully sued by the Israeli researcher who had assembled it. While the court decided to apply Israeli legal standards in determining originality, perhaps in a different instance of international copying, US law could be applied.[46]

Manuscript Digitization Copyrights

What does this mean for manuscript digitization? In any of the major jurisdictions of concern—the US, the UK, the EU, and Israel—these simply aren’t subject to copyright. In the US, this has been demonstrated most directly with Bridgeman Art Library Ltd. v. Corel Corp (1999) where color transparencies of public domain paintings were concluded to be ineligible for copyright protection under either US or UK law. Such claims to copyright are simply claims. For these institutions, there is little to no downside with making these claims, and the upside is substantial. One legal reviewer frames the motive this way: “asserting copyright ownership will allow museums greater control of their collections and create lucrative revenue streams.”[47]

Of course, there may be other strategic motivations as well. In 2014, the present author had an opportunity to attend a Daniel B. Wallace presentation on the text of the New Testament and I asked about this afterward. The conversation went something like this:

CO: Why do you assert copyright on the digitizations produced by CSNTM?

DW: The manuscripts themselves may not be under copyright, but the photographs are.

CO: There is court precedent indicating those claims aren’t legitimate.

DW: Well, we can’t release them under different terms because we have contracts in place with these institutions and need to uphold them to continue working with them.

CO: <hands card> Please contact me if you’d like help with releasing these more freely. I’d love to see the word of God in the hands of the people of God.[48]

Critical Text Copyrights

What does this mean for critical texts and diplomatic editions? If a work purports to restore some original, what grounds is there for a claim to copyright? Critical texts ought not be artistic works of creativity, but exercises in scientific rigor. For example, the Robinson/Pierpont Majority Text is not much more than an exercise in variant counting, albeit an intensive one. On one hand, their public domain dedication is most laudable; on the other hand, their assertion of copyright to make such a dedication is most laughable.

More eclectic approaches to textual criticism might have more grounds by which to argue originality, “a modicum of creativity.” Perhaps one might say the editorial choices involved are artistic in nature or that the use of medieval characters and punctuations make them necessarily derivative. However, the degree to which one concedes true derivation is the degree to which they concede failure in the task of scientifically restoring the original text.

In fact, if one has done the task of textual criticism perfectly, he would arrive at the original work, a public domain text. At this point, the grounds for originality is error. Maybe one would be so bold as to argue this without irony, but would such a claim even be legitimate? The notion of creativity relies on some notion of intent; would these be intentional errors? If so, how could the recipient of the work be aware of this? Of course, we are offering more questions than answers, but the absurdity of the situation should be evident.

While the originality of such works has been upheld in Israel, at least one case in France has concluded that editing a critical edition does not generate a copyrightable work.[49] In the US and UK, there should be even less ground for such an assertion.

A Biblical View

Having surveyed the ownership of manuscripts and critical texts, we ought to step back and ask who should own the manuscripts and critical texts.

Physical Ownership of Manuscripts

Biblically, there can be no objection to various MSS being owned by various individuals and organizations. The legitimacy of property was established with the command to take dominion and reinforced with the ninth commandment. While the original autographs may be labeled as a gift of God made directly to the church that cannot be owned, physical copies cannot be labeled similarly.

However, the ownership of antiquities is frequently complicated by patrimony laws. For example, in United States of America vs. Approximately Four Hundred Fifty (450) Ancient Cuneiform Tablets; and Approximately Three Thousand (3,000) Ancient Clay Bullae, Hobby Lobby was forced to forfeit a number of artifacts and MS fragments to Egypt and Iraq because of a lack of provenance. In other words, the law in many jurisdictions permits the state to claim ownership over antiquities independent of any real possession.[50] While this may match modern sensibilities on preserving heritage, it is difficult to establish any justification for this from the Scriptural notion of property.

Ownership of Manuscript Digitizations

Given that the Bible does not treat ideas as property, and that copyright is relatively novel, being an 18th-century invention,[51] there are reasons to reject the legitimacy of copyright altogether.[52] However, because the laws of relevant nations almost—if not completely—universally regard mechanical reproductions of public domain works as being in the public domain, we may concede this point for the sake of discussion.

However, even apart from actual copyright, the claims to copyright impose a serious chilling factor on profitable uses of MS digitizations. At a minimum, it prevents archivists from republishing these digitizations for the public. Anyone who spends some time exploring the available data will frequently run into outdated information and HTTP 404 errors. One website that displays early papyri, earlybible.com, lacks 𝔓66 because the purveyor was repeatedly threatened with legal action.[53]

One substantial barrier to progress in this area is that there is rarely any penalty for falsely asserting copyright on that which cannot be copyrighted. The law of Moses contained the following protection for innocent parties:

If a false witness testifies against someone, accusing him of a crime, both parties to the dispute must stand in the presence of the LORD, before the priests and judges who are in office at that time. The judges shall investigate thoroughly, and if the witness is proven to be a liar who has falsely accused his brother, you must do to him as he intended to do to his brother. So you must purge the evil from among you. Then the rest of the people will hear and be afraid, and they will never again do anything so evil among you. You must show no pity: life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, and foot for foot. (Deuteronomy 19:16-21)

Because false accusation attempts to commit real property harm toward neighbor, it would be just to have a similar provision in our own law. Museums and other institutions should not be able to claim copyright on public domain images and litigate without penalty.

Critical Texts

If critical texts purport to actually restore the words of the prophets and apostles, then clearly it cannot be subject to human ownership. The word of God was given as a gift and cannot be owned or sold (2 Cor 2:17). Even measures of inaccuracy in the restoration do not change this reality. Even claiming a right to attribution goes beyond what can be biblically granted, as in the case of the SBLGNT.

Likewise, truth itself is not something that can be owned. Even those organizations that make minimal claims on associated metadata to critical texts make too much of a claim. For example, Open Scriptures claims that the lemma and morphology data they publish alongside the OSHB is licensed under CC BY, but these are merely factual assessments of syntax and grammar, not creative works.

Conclusion

The manuscripts and critical texts of Scripture constitute a complex landscape of ownership. While it is appropriate to treat physical manuscripts as property, Scripture itself should not be subject to ownership. The word of God should not—and cannot—be bound (2 Tim 2:9).

“Jordan files complaint over Dead Sea Scrolls: Allegedly stolen during Six-Day War,” The Christian Century, Februaray 9, 2010. “Israel says Palestinians may try to claim Dead Sea Scrolls,” The Times of Israel, November 6, 2016. ↩︎

Tamar Mskhvilidze, “The Dead Sea Scrolls Case: Features of Intellectual Property Disputes in Private International Law.” (2022). Law and World, 8(23), 184-200. https://lawandworld.ge/index.php/law/article/view/327 ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/Leningrad_Codex_Color_Images/ ↩︎

https://aleppocodex.org/; Private email with Ardon Bar-Hama. ↩︎

https://www.ifla.org/g/cch/hebrew-manuscripts-digitisation-project/ ↩︎

https://www.nli.org.il/en/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/terms-of-use ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

https://iiif.bl.uk/uv/#?manifest=https://bl.digirati.io/iiif/ark:/81055/man_10000000.0x000001 ↩︎

https://www.die-bibel.de/en/biblia-hebraica-stuttgartensia ↩︎

https://openscholar.huji.ac.il/bible_project/hebrew-university-bible-project-hubp ↩︎

https://www.magnespress.co.il/PDF_files/review_of_%20The_%20book_of_Ezekiel.pdf ↩︎

https://www.sbl-site.org/sbl-press/browse-books/the-hebrew-bible-a-critical-edition/ ↩︎

https://www.amazon.com/Proverbs-Eclectic-Introduction-Commentary-Critical/dp/1628370203 ↩︎

https://tyndalehouse.com/research/the-greek-new-testament-produced-at-tyndale-house/ ↩︎

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Mat%201&version=THGNT ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/nestles-greek-new-testament-bfbs-and-us-editions-1904-with-translation-1905 ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/1550-stephanus-textus-receptus ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/greek-new-testament-scrivener-textus-receptus-1894 ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/Tischendorf.I.GreekNewTestament.NovumTestamentumGraece.various/ ↩︎

https://archive.org/details/RP2005KoineGreekNTinByzantineTextform/page/n5/mode/2up ↩︎

Jane C. Ginsburg, “No ‘Sweat’? Copyright and Other Protection of Works of Information after Feist v. Rural Telephone,” Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive (1992): 338-388 https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1060&context=faculty_scholarship ↩︎

Urzula Tempska, “‘Originality’ After the Dead Sea Scrolls Decision: Implications for the American Law of Copyright,” Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review 6 (1 2002): 119-146 https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=iplr ↩︎

Tamar Mskhvilidze, “The Dead Sea Scrolls Case: Features of Intellectual Property Disputes in Private International Law.” (2022). Law and World, 8(23), 184-200. https://lawandworld.ge/index.php/law/article/view/327 ↩︎

Colin T. Cameron, “In Defiance of Bridgeman: Claiming Copyright in Photographic Reproductions of Public Domain Works,” Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal 15 (1 2006): 69 https://tiplj.org/wp-content/uploads/Volumes/v15/v15p31.pdf ↩︎

He did not take me up on the offer. 🫠 ↩︎

Jugement rendu le 27 Mars 2014, Tribunal De Grande Instance De Paris. https://apocryphes.hypotheses.org/files/2014/04/jugement-garnier-droz.pdf; see also https://apocryphes.hypotheses.org/389 ↩︎

See also United States v. Schultz. https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/resources/culturalpatrimony/2571.html ↩︎

Private correspondence with the owner of earlybible.com. ↩︎