“Everything’s for sale in the 21st century,” sang Derek Webb in his song Ballad in Plain Red (2003). Hyperbole? As I look around, I see Christian speakers charging fees for conferences, pastors requiring payment for digital sermon downloads, biblical commentaries and books about the gospel being sold, Christian bloggers monetizing their writing about Jesus through paid subscriptions and advertising, and worship artists selling the rights to sing their songs to God in church.

But this isn’t new. Truth was already being sold way back in the 8th century BC in the time of the prophet Micah, and what he wrote has implications for today’s monetizing of ministry. So, I invite you to join me in taking out the microscope and meditating on Micah 3:11. The prophet is speaking of the nation of Israel:

Its leaders give judgment for a bribe;

its priests teach for a price;

its prophets practice pagan divination for money.

Yet they lean on Yahweh and say,

“Is not Yahweh in our midst?

No disaster shall come upon us.” (Micah 3:11)

We have three parallel lines in this part of the poem: 1) leaders taking bribes, 2) priests selling their teaching, 3) prophets selling divination. If we didn’t have the first line, we might mistake the second two lines as things that are actually okay because of how normal they have become in our current commercialized Christian climate. But the first line is something we still universally recognize as wrong. Bribery within the justice system is obviously sinful to everyone.

“Its priests teach for a price”

Although not everyone is in agreement on how to translate the Hebrew root ירה (yarah) in line two of this verse, the consensus is that it has to do with instruction (NASB) or teaching (NIV). This is the same verb used to talk about the role of the priests in Deuteronomy 33:10: “They shall teach Jacob your rules and Israel your law” (see also 2 Chron 15:3, Deut 17:10-11, 24:8, Lev 10:11, 14:57, Ezek 44:23). So in the time of Micah, these spiritual leaders were teaching. About God and his word. And this teaching had a price tag.

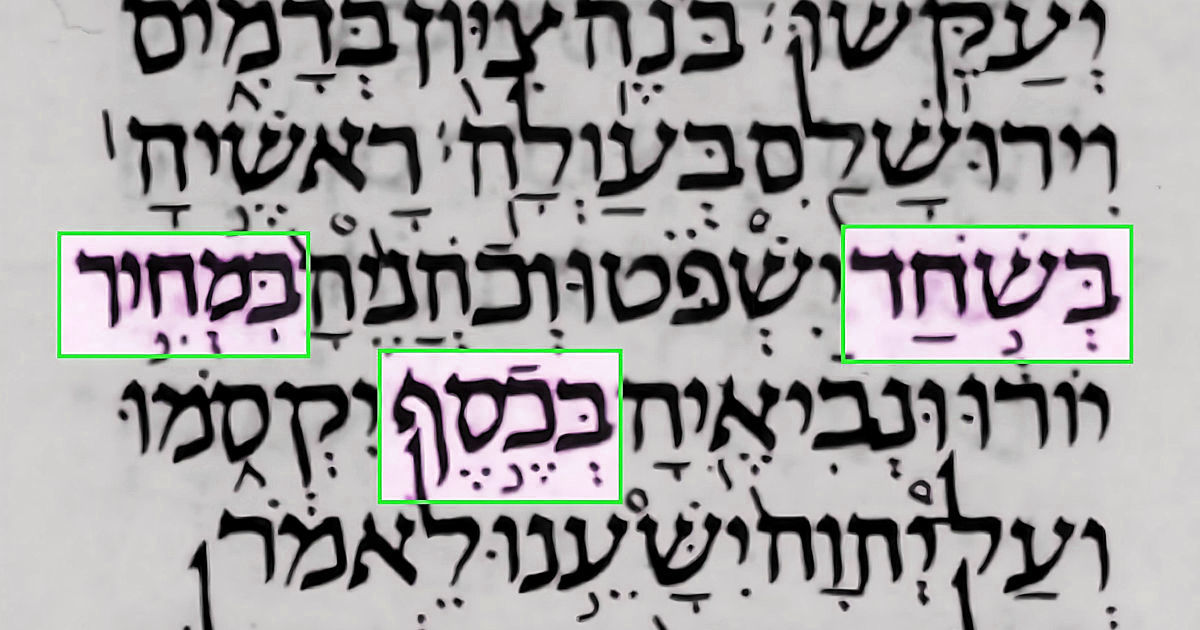

In the phrase “priests teach for a price” the Hebrew word for “price” (מְחִיר, mechir) speaks of the simple idea of requiring payment. To be clear, these priests were not condemned by God for charging more than usual, nor for making more money than they needed to live on. It was simply for monetizing their role as servants of Yahweh. God was already providing for their needs in other ways (Num 18:11), but they were using their position to invent ways of increasing their income. Christian history has used a strong, specific word for this sin: venality, defined as “the prostitution of talents, offices or services for reward.”

Don’t miss the fact that in this verse, selling godly instruction is likened to the sin of taking a bribe as a judge—unjustly favoring those who can pay in the court of law. Therefore, God condemns the sale of Christian instruction.

“Its prophets practice pagan divination for money”

The third parallel line of the verse speaks of prophets doing divination (Hebrew קסם, qasam) for money. In English the word “divination” can be ambiguous, referring to general prediction performed under divine inspiration. But in both the Hebrew original and the Septuagint translation, the words used are unambiguously negative. In Greek the word (μαντεύομαι, manteuomai) here refers to what we see in Acts 16:16 with the slave girl who was used to make money through fortune-telling. In Hebrew the verb (קסם, qasam) is exclusively used in negative contexts, such as those condemning false prophets (e.g. Ezek 21:29, Jer 27:9, Zech 10:2). It was forbidden in Deuteronomy 18:10: “There shall not be found among you anyone who burns his son or his daughter as an offering, anyone who practices divination (קסם, qasam) or tells fortunes or interprets omens, or a sorcerer.” We know from 2 Kings 17:17 that Israel was guilty of this sin.

Micah doesn’t use the usual Hebrew verb for “prophesy” (from the root נבא, nava’) here, and to the original hearers it would have been especially shocking because of how unexpected it was after the first two parallel lines. In those lines he describes the leaders and priests doing expected things: judging (שׁפט, shaphat) and teaching (ירה, yarah), but then jars the listener with the action of these prophets. Unfortunately, the NLT fails to reflect both the negative connotation and surprise: “you prophets won’t prophesy unless you are paid” (see also the GNT “give their revelations” and ISV “prophesy”).

So there are actually two evils described in this third line of the verse: 1) doing pagan divination, and 2) the act of selling it. How do we know that selling the work of prophets was wrong? 2 Kings 5 gives us an example of how strict good prophets were about not even accepting offered remuneration for their righteous work, in the story of Elisha and Gehazi. When Gehazi did what he thought was reasonable in his own eyes, and accepted what Naaman offered as a payment of gratitude for his healing, the consequence was severe (5:26-27).

Once again, don’t miss it: the evil of selling divination is something God likens to priests who sell teaching.

“Yet they lean on Yahweh”

The last half of Micah 3:11 shows that the corruption is all the worse because it’s hidden behind a show of piety: “Yet they lean on Yahweh and say, ‘Is not Yahweh in our midst? No disaster shall come upon us.’” Some may say this sincerely, and others insincerely. But either way, Micah is pointing out a dark irony—these spiritual leaders are claiming to trust in Yahweh, and they believe that he is present among them as a sign of approval of what they’re doing. They reassure themselves by the outward performance of religious rituals. But the end result will be destruction: “Therefore, because of you Zion shall be plowed as a field; Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins” (Micah 3:12).

Have we now moved past this temptation and practice? We still find non-profit organizations, authors, worship songwriters, biblical counselors, Bible publishers, and many others sincerely believing that it’s ok for them to be selling access to the truth they offer through their ministry of the Word. We often misapply Scripture to justify this practice with phrases like: “A worker deserves his wages” or “How else would they make a living?” or “Paul said that charging money for ministry is one of my rights”. But in spite of our reasoning, the sincerity of monetized ministry is compromised, and God likens it to 1) a judge taking a bribe and 2) a prophet using pagan forms of prediction and charging money for it.

Perhaps it’s not an accident that in Judges 17 we meet a man also named Micah, who instead of condemning corruption, offers a Levite money to be his priest. Micah is a desperately confused man. He’s convinced that God will bless him because 1) he has two expensive idols in his house (17:4) and 2) he paid a descendent of Levi to be his priest (17:10). The interesting thing about both Micah and the Levite is that they are well-meaning, and apparently oblivious to the evil of their actions. The Levite is never named by the author, probably to imply that the entire priesthood has become corrupt, and to highlight the degradation and lawlessness during this period where “everyone did what was right in his own eyes.”

Responding well

All of this compels me to ask just a few questions: Could it be possible that the richest, most materialistic societies in all of human history (Western nations) might have a tendency to do what is right in their own eyes regarding money and ministry? Could it be that we are partaking in our culture’s serious blind spots when it comes to the commercialization of Christianity? Might we be just as confused and well-meaning as Micah and the Levite, oblivious to the evil that God sees in us?

Over two thousand years later, are we—the church of the 21st century—guilty of the prophet Micah’s indictment? In our cultural moment we have mostly accepted the peddling of God’s word as normal: priests teach for a price all around us. Spiritual leaders are selling biblical teaching—in many forms and contexts. Digital books full of lifegiving, gospel truth have price tags, Bible study software is sold, videos to help people go deeper into the Bible are carefully guarded behind paywalls. But God’s heart remains clear in Scripture: “let the one who is thirsty come; let the one who desires take the water of life without price” (Rev 22:17, cf. Isa 55:1).

Just like in Micah’s time, most of us today assume we’re doing nothing wrong when we turn the knowledge of God into a profitable product. After all, seemingly everyone around us and even those leaders we love and respect are doing the same. Surely so many people can’t be wrong, we think. And yet every culture has its blind spots, as Christian history has shown. How can we discover them except by returning over and over to Scripture to be informed and admonished as we discover what God desires and requires of us?

As with all prophetic critiques of well-established cultural practice, people almost never respond well. This is true of Micah’s day and ours, especially when money is mentioned. Scripture has given an example of how it often goes when someone challenges our attachment to worldly wealth and ways of amassing it. After Jesus gave the rich young ruler a hard assignment, “he was deeply dismayed and he went away grieving; for he was one who owned much property” (Mark 10:22), or as Matthew 19 says: “he went away sorrowful, for he had great possessions.”

So, I will not be surprised if many who monetize ministry simply dismiss this. I’ll also not be surprised if some agree and say, “Yes, Scripture does condemn requiring payment for ministry. Instead, I should follow Jesus’ instructions to give freely, and rely on my Master to provide for me,” but then go away sorrowful, because change is too hard. They’re too entrenched in the status quo. Or there’s too much money at stake, and there are so many systems in place that have made themselves part of the very fabric of our organizations—systems which would need to be painfully uprooted. It’ll probably be too uncomfortable. Tearing down idols is hard. Following Jesus is hard, and deeply uncomfortable, especially when you have a ship that you’ve built up over decades until it’s too big to turn.

When Jesus entered the temple courts in Matthew 21:12, he didn’t have a nice friendly conversation or soft-spoken debate with those who were buying and selling there. There was no feigning of neutrality. Instead, he drove them out and overturned the tables of the money changers and the benches of those selling doves. Some may not have ears to hear a message like Micah’s, and perhaps Jesus will respond with a violent wake-up call in their lives, painful and jarring. Yet my hope and prayer is that Western churches are not so full of money changers and sellers that the only way for change is for Jesus to resort to driving them out by force.

Let’s pray for reform, so that some things are considered too sacred to be for sale in the 21st century. Instead of selling it, let’s freely speak truth in love. And let’s honor and imitate our perfect Judge, Priest, and Prophet who never sold his teaching—who gave his life for greedy people like you and me.