You’re at church and it comes time to pray together. The person assigned to pray has decided to recite a lovely piece by another author. They display it on the screen for everyone to read. At the end of the prayer you notice the following:

“How Great Our God Is” words by Tom Christie

© 2004 Wondrously Made Prayers

Used by permission. PPLI License #12345

You’re a bit confused by this, so you decide to ask the pastor about it after the service. He explains that the church has signed up for an annual license to be able to legally recite prayers during services.[1] The church now needs to pay an annual fee and report what prayers are prayed each Sunday to avoid infringing the law. While they don’t plan on praying copyrighted prayers from other authors every Sunday, they need to pay the annual fee anyway. The pastor was at least thankful they could be supporting the work of the prayer writers, who do need to feed their families after all.

While praying published prayers by other authors is usually only common in more liturgical services, the idea of needing to pay to have permission to publicly pray them would be disturbing to most people. Prayer is direct communication with God, and any kind of commerce has no place in such a sacred act. Yet the business model I’ve just described is a direct reflection of what currently happens with worship music.

The Worship Music Industry

Modern worship songs are almost always copyrighted. While it is very simple to waive copyright restrictions, few artists have chosen to do so. As a result, churches have been limited to either singing old hymns or paying annual licensing fees to use modern songs in their services. For churches that do not want to be left in the past, that has not been a realistic choice.

Nevertheless, many churches are more than happy to comply with this requirement, since they believe it is appropriate to support Christian artists. And it is appropriate to support Christian artists (we’ll return to this later). But where does the “support” actually end up going?

The reality is that most Christian artists will remain in obscurity while a select few rise to the top and have their songs sung in a large number of churches. Some of these artists charge up to $50,000 USD for a single performance at an event[2] in addition to the large amount of royalties they collect from churches.[3] Any subsequent songs they publish are almost certainly guaranteed to make a profit, regardless of their quality. Whether they continue to write songs or not and whether they stay Christian or not,[4] the money continues to flow. Meanwhile, many other artists cannot earn anything close to a living wage from their music alone and must support themselves by other means. There is a disparity between the artists who need financial support and those who actually receive the proceeds from licensing fees. Instead, the current system follows the celebrity model of the secular music industry.

Many of the songs that do become popular come from groups with questionable practices or theology.[5] The most prominent examples are the bands associated with Hillsong, Bethel, and Elevation. According to licensing statistics, at least half of the top 100 worship songs used in church services are by artists with strong connections to one of those three.[6] Some of the royalties for those songs are even paid directly to those churches.[7] While some churches have chosen not to sing their songs, statistics show that a great many still do. Therefore, much of the money churches pour into the music industry goes to artists who already have more than they need, or to entities with whom it would be unwise to be financially connected.

The Business Facilitator – CCLI

The main organization that facilitates this business model is Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI) which is used by over 250,000 churches in at least 70 countries.[8] Other licensing organizations exist, but they are focused on different use cases, so CCLI has a virtual monopoly on the standard licensing necessary for contemporary services.[9]

CCLI originally came about due to a fear that churches could be sued for copyright infringement by Christian artists. They point to a case from 1984 where an author of songs such as “They’ll Know We Are Christians by Our Love” sued a Catholic diocese in Chicago (see 1 Cor 6).[10] Despite this legal precedent, I do not know of any other cases where Christian artists have tried to sue churches.[11] Nevertheless, one of the reasons CCLI gives for why churches should pay for their licenses is to ensure that they are legally “covered” from such lawsuits.[12]

Though it describes itself like a ministry[13] and originates from a church in the United States, CCLI has always been a for-profit private company.[14] In 2016, the business was sold to a secular company that also sells music licenses called SESAC.[15] This might seem like a natural fit, since they both have similar business models, but they do not have similar clientele. CCLI exclusively serves Christian artists and churches, and even identifies as Christian in its name, yet is now under secular ownership and control.

Presumably, the owner of CCLI carefully looked into SESAC before selling a Christian business that 250,000+ churches rely on and pay millions of dollars to. At the time of the CCLI sale, SESAC was primarily owned by Rizvi Traverse Management,[16] a private investment firm which also owned a significant part of Playboy (the pornography business).[17] SESAC has now been sold (and CCLI along with it) to another investment firm called Blackstone.[18] Blackstone owns many different companies, some of which have concerning practices.[19] But their main goal, like any investment firm, is to simply maximize profits for their shareholders.

This is a screenshot of the public portfolio page for the primary owner of SESAC prior to the sale of CCLI to SESAC.[20] Noting that the owner (Rizvi Traverse Management) did not merely invest in SESAC but had a controlling interest (at least 75%) and also had an influential stake in Playboy.

To be clear, the issue here is not that CCLI is engaged in any disreputable business, but rather that it has been entrusted to the owners of disreputable businesses. These owners now also profit off of the worship of God. Even if CCLI hadn’t been sold to a secular company, there is no reason why it should have been for-profit in the first place.

CCLI only offers annual licenses, which are not based on how many songs are sung in church services. While this can be administratively convenient, it also means churches continue to pay even if they sing public domain songs. A church that mostly sings old hymns and only uses modern copyrighted songs 10% of the time will still pay as if they had used them 100% of the time.

Artists themselves have also taken advantage of public domain hymns by tweaking them and subsequently collecting royalties for their new version.[21] No one collects royalties for the original Amazing Grace.[22] Chris Tomlin and Louie Giglio’s version has since become extremely popular. It is the 20th most popular song on CCLI at the time of writing. The success is clearly not due to the added chorus alone. Many churches that would have been regularly singing the original Amazing Grace are now singing Tomlin and Giglio’s version, providing the owners with abundant royalties.

Secular Investors

CCLI is not the only party entangled with secular investors. It has recently become popular—thanks to new platforms—to sell song rights to investors. Songs earn royalties for both the artist and the publisher, often split 50/50 between them. It is unclear how much involvement artists have in these auctions as many appear to be initiated by publishers for their share of the royalties.[23] The following are examples of worship songs that have had a portion of their royalty rights sold to investors:

- The Lion And The Lamb – Leeland[24]

- I Worship You, Almighty God – Sondra Corbett-Wood[25]

- Ever Be – Kalley Heiligenthal[26]

- Forever – Kari Jobe[27]

While not designed for corporate worship, many other Christian artists also have songs that have been sold to investors, such as TobyMac, Lecrae, Trip Lee, Kutless, Unspoken, Michael W. Smith, Micah Tyler, Sanctus Real, Tauren Wells, and the list goes on….[28]

Investors certainly see CCLI as an avenue for profit. One musical rights auction remarks, “this catalog earns royalties from a unique and lucrative source: direct licensing to churches [via CCLI].”[29] As Kelsey Kramer McGinnis points out in her insightful article on this practice, the more secular investment there is in Christian music, the more incentive there will be for investors to influence what songs churches sing.

This is not necessarily new or limited to songs that have been put up for auction. Many Christian worship songs are published by for-profit entities that are owned by secular investors. The largest entity is Capitol Christian Music Group (CCMG) that claims “its publishing division currently has a 60% market share of the Top 10 songs sung in church in the United States each week.”[30]

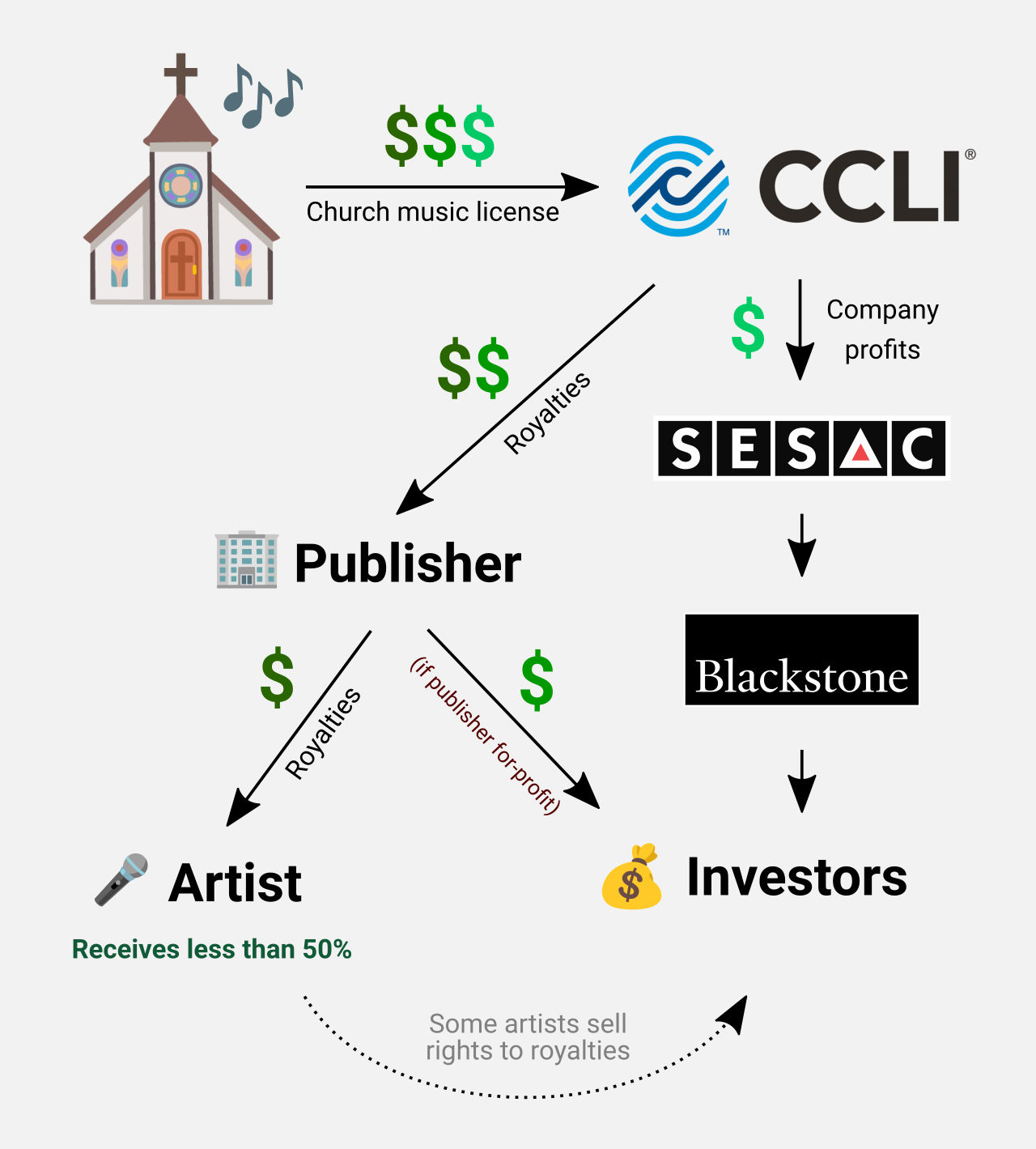

So whether auctioned or not, many Christian songs are already benefiting secular investors. CCLI likely takes around 10-15% before distributing royalties.[31] Assuming the common 50/50 split for publishers and artists, artists will end up taking less than 50% home, with the rest eventually flowing down to investors. Some publishers are non-profit,[32] but all of them still collect royalties through CCLI. So while it may be claimed that the licensing system is “supporting” Christian artists, it is also profitable to secular investors who may be taking in even more.

Where the money churches pay in licensing fees goes in most cases.

The Sanctity of Worship

While all these matters are concerning, they are merely symptoms of the root theological confusion most Christians have about the commercialization of spiritual things: that it is permissible so long as it is practical. Some may object: Why can’t CCLI operate like any other business? What’s wrong with artists making money from songs that belong to them? Why can’t they sell rights to royalties if they want to? All of these objections have a common assumption: that there are no biblical prohibitions against commercializing ministry.

Interestingly, secular society has a higher view of worship music in this regard than many Christians do. In 1976, when U.S. copyright law was revised, an exemption was added for religious services[33] which still remains today:

“the following are not infringements of copyright: […] performance of a […] musical work […] of a religious nature, or display of a work, in the course of services at a place of worship or other religious assembly.”[34]

The rationale for this exemption is revealed in this analysis provided with the original submission: “The purpose here is to exempt certain performances of sacred music.”[35] That is, the reason why Christians should be able to sing songs for free in church is because they are sacred, they are distinct from other songs because of their spiritual nature.

Even in countries without such a legal exemption, secular licensing organizations may waive requirements for religious services. In Australia, there is an industry consensus that churches should not be charged to sing songs in worship services. As stated by the primary licensing organizations: “APRA AMCOS does not require a licence to be obtained for worship or divine services.”[36] Unlike the U.S. exemption, it does not specifically mention the display of songs and APRA AMCOS did not respond to my inquiries.[37] Nevertheless, the intention appears to be the same, to prevent sacred worship from being commercialized.

An Outdated Exemption

So, why do churches pay for a license?

When the U.S. religious exemption was added in 1976, most churches would have been singing from memory or song books. The main need was just to be able to perform songs without legal restriction. It was only after overhead projectors became popular in the 80s that churches began copying lyrics themselves,[38] first onto transparencies and then later into digital presentations. Since the exemption only applies to the performance and display of a song, copying lyrics is not technically covered by the exemption.

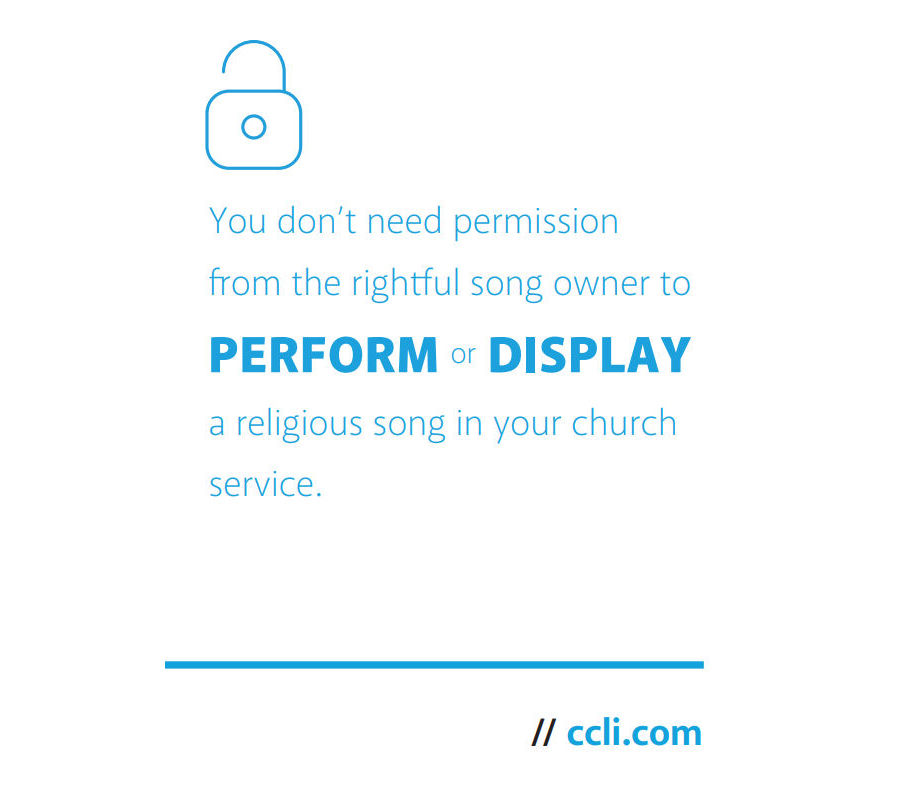

This is why when you pay for a CCLI license you are not paying for permission to perform the song at church. That right is covered by the religious exemption.[39] This has been confirmed by CCLI themselves.[40] Instead, when conducting a simple non-recorded service, you are merely paying for the permission to copy the lyrics into digital slides for the song you are already allowed to sing. If, however, you print, record, stream, or translate the song, then those activities would not necessarily be covered by the exemption.

In other words, for all American churches that merely project lyrics onto a screen without streaming their services (which was most churches prior to COVID-19), they are allowed to sing without a license, play the music without a license, and display the lyrics without a license. The only things in question are printing music sheets (which musicians could buy or memorize instead) and copying the lyrics into physical or digital presentations so they can be displayed. So it is the single act of copying lyrics into slides that churches pay CCLI for, not the actual display of those lyrics which is already allowed.

U.S. copyright law explicitly permits performing and displaying religious songs in religious services, but does not explicitly permit the act of copying lyrics into physical or digital presentations.

CCLI acknowledges the triviality of this legal gap in one of their factsheets: “The DISPLAY aspect sets up an interesting dichotomy for worship leaders. Apparently the law allows you to DISPLAY lyrics for copyright songs without permission, but it doesn’t allow you to REPRODUCE song lyrics, or store them in a computer.”[41]

From a CCLI factsheet on the U.S. religious services exemption.

However, U.S. copyright law does have general “fair use” exemptions, and one of the main factors considered is: “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature.”[42] Since copying lyrics into slides for use in church is (1) non-commercial, (2) trivial, done solely to facilitate the legal display of the work, and (3) only creates a single private copy inaccessible to the public, it is highly likely it would be considered fair use. Since this kind of case has never been considered in court, CCLI and Christian artists will be able to continue to cast doubt on its legality until someone attempts to sue for it. We can be assured, however, that the original purpose of the religious exemption was to prevent such issues from ever arising.

Exploiting the Legal Gap

From the days of the early church to the Reformation and beyond it, the sanctity of worship was mostly kept pure from commercial practices. Even secular lawmakers have sought to preserve it. So when advances in technology put the religious exemption into question, what did the Christian music industry do? Rather than seek to affirm and clarify the exemption, they have exploited the legal gap and sought to profit from the worship of God. Not all artists would be aware of the exemption, but even those who are have continued to commercialize their songs.

Churches that wish to translate songs for another language, or benefit from modern day advances in recording and streaming technology, must pay a premium to do so. The Christian music industry would have greatly profited from the COVID-19 pandemic since many churches were forced to pay for streaming licenses to stay connected with their members.[43] Those that do pay for licenses also have the additional burden each week of having to report what songs they sing, every time they sing them. Congregations are being burdened financially and administratively by fellow believers who do not even participate in their services.

Churches that are unmotivated or ignorant of these legal restrictions are made lawbreakers by fellow believers. This includes believers in persecuted churches who often love to translate and sing Western songs (without permission). CCLI includes as its clients countries where most of the population still live in poverty, such as Malawi and Mozambique. Compliance with copyright restrictions should not be something congregations in these countries need to think about.

Reform

All Christian artists who produce music to edify the church should release their songs free of cost and copyright.

Selling Jesus has published numerous articles on why commercializing any form of ministry is a violation of Scripture’s clear teaching. These resources also address common objections that arise when the monetization of ministry is confronted. One common objection is that passages such as 1 Corinthians 9 and 1 Timothy 5:18 (“The worker is worthy of his wages”) teach that any ministry can be sold. However, both passages are in the context of those freely giving ministry, not selling it. A second common objection is that Romans 13:1 (“Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities”) encourages the exploitation of secular copyright law. On the contrary, it does not require any such thing, and artists are free under the law to waive restrictions if they wish to.

This is not to say that Christian artists shouldn’t be supported, or that they have bad intentions when they participate in licensing schemes. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, it is appropriate to financially support Christian artists, just as it is appropriate to support anyone who is involved in ministry.

While we can certainly sympathize with the good intentions of most artists, that is not a reason to dismiss Christ’s clear command and example. When he entered the temple and discovered it had become a marketplace (John 2:13-17), he was angry—angry enough to drive out and turn over the tables of all those seeking to profit from worship. Some will be quick to object that this took place in the temple which was holy and cannot be equated with churches today. Yet the very act of worshiping a holy God is a sacred act. Jesus was angry with people selling ordinary things in a place of worship, whereas what is happening today is not the sale of ordinary things, but spiritual things. They are “spiritual songs” (Eph 5:19, Col 3:16) exclusively about and directed towards our holy Lord.

These practices are so ingrained in the industry, both culturally and legally, that reform for existing artists will be difficult. Songs that are (1) modern, (2) congregational, and (3) copyright-free are very difficult to find. Should we then turn a blind eye and shrug because things are unlikely to change? That is not a biblical response that honors God. Instead:

- Pastors should start actively raising up a new generation of musicians, teaching them about the sanctity of worship, and admonishing them against any commercialization of it.

- Musicians should release new songs into the public domain and start to build a collection churches can use for free. Those who hope to be supported in this work should ask God to provide through his people, just as pastors and missionaries do.

- Churches in the United States that are willing to forgo streaming their services could sing copyrighted music under the U.S. religious exemption if they wish to,[44] but the future eventually needs to be free of commercial worship music altogether.

Whether immediate or gradual, Scripture requires all churches to abandon this unbiblical system. Let’s pray that believers go “back to the heart of worship” and say “I’m sorry, Lord, for the thing I’ve made it,” so that it really is “all about you, Jesus.”[45]

When contemporary Christian music first started to emerge—and be commercialized—one artist refused to profit from the gospel. Keith Green, one of the most popular Christian artists of his time, was adamant that “if it’s ministry, you cannot charge.”[46] Keith didn’t want anyone to be impeded from hearing the gospel through his music, and was convicted to not charge for tickets to his concerts (which thousands attended) and gave away records for free.[47] He died in a tragic accident at the age of 28, but his music continues to impact hundreds of thousands of people today. Artists have their role model, a man who refused to compromise and took seriously Jesus’ words: “freely you received, freely give” (Matt 10:8).

CCLI was sent a draft of this article prior to publication and was invited to give a response that would be published with the article. They did not respond.

While being fictitious, this illustration is actually close to reality. Published prayers are copyrighted and reciting them in public may infringe the law, especially if the service is recorded or the prayer is copied into booklets or digital slides. Some ministries are already licensing liturgies for church services based on how many people attend. ↩︎

From someone who has booked many Christian artists for events: “The common number for mid level christian artists is $50,000, and some of those artists will charge that per day/performance. So if you book someone for two performances over 48 hours, it’s $100,000, excluding travel expenses, meals, hotels, etc. I just recently worked with an organization who booked a lower level christian Artist, much less known, for $20,000 for one hour, plus first class flights, sound equipment rental and hotel. These prices are just for solo performances. If you want to book one of these artists with their entire band, you’re looking at upward of $75k per performance.” ↩︎

The Lion And The Lamb produced around $80-90k in CCLI royalties in a single year. Most popular artists will have several big hits, easily exceeding $100,000 in royalties from churches each year. ↩︎

Such as Jon Steingard (Hawk Nelson) and Marty Sampson (Hillsong). ↩︎

See this discussion on the theology and practices of some of these churches. ↩︎

Based on CCLI’s top 100 songs in the US on 6 Feb 2024. ↩︎

For example, Hillsong collects the performance royalties for songs by its artists. ↩︎

From the CCLI founder’s website. ↩︎

As described by CCLI themselves: “CCLI, Christian Copyright Solutions (CCS), and OneLicense are all organizations which provide licenses to churches and Christian ministries. However, rather than being in competition, each company represents different rights […] While there may be a small overlap, generally OneLicense represents the catalogs of liturgical music publishers, while CCLI represents a much larger, more ecumenical list." ↩︎

As explained by CCLI: “Our story begins in 1984 when a Portland, Oregon pastor first learned of a pending $3.1 million copyright lawsuit against the Archdiocese in Chicago”. They refer to a case where a Christian publisher sued a Catholic church diocese over a disagreement about copyright infringement and subsequent responses to it. While the publisher was initially awarded $3.1 million, there was later an appeal and they only ended up receiving $190,400. The publisher later shut down, likely due to losing the business of those who have a “preference to deal with suppliers of liturgical music that have not threatened to sue their customers”. ↩︎

Even before a substantial number of churches legally protected themselves with CCLI, I still do not know of any other cases of artists trying to sue churches. ↩︎

From CCLI’s website: “The law is clear on copyright. Now you’ll know the church is covered, as well.” ↩︎

From their history page: “Our roots began as a ministry of the church… we remain evermore committed to that cause”. In other words, they initially identified as a ministry, and whether one would classify them as a ministry or not, they are committed to acting like a ministry, and provide services almost exclusively to churches. ↩︎

It is assumed that it was originally owned by its Christian founder, Howard Rachinski, though there may have been other investors with shares as well. ↩︎

As revealed in this article. ↩︎

Rizvi Traverse Management bought a 75% stake in SESAC in 2013. ↩︎

Rizvi Traverse Management helped to privatize Playboy in 2011 and still owns part of it at the time of this article. ↩︎

Blackstone acquired Rizvi’s stake in 2017. It is reported that Rizvi’s stake had grown to at least 82% by the time Blackstone purchased it. Since SESAC describes itself as being owned by Blackstone, it is assumed Blackstone also purchased the rest of the company from the other shareholders as well. ↩︎

See this criticism section. ↩︎

Taken from this archived copy of the page in late 2015 prior to the sale of CCLI sometime in 2016. ↩︎

This is similar to what Disney has done with public domain fairy tales. While the original stories are still around, it is Disney’s versions that have become popular and Disney enjoys exclusive rights to them. ↩︎

Since churches pay annually for a CCLI license and cannot report singing public domain songs, the money that would have gone towards such a song presumably just adds to the value of all other songs. ↩︎

Since many auctions include a number of songs from multiple artists, they are more likely to be the publisher’s rights. However, some auctions do explicitly mention that the songwriter’s rights are being sold. ↩︎

An auction that included The Lion And The Lamb. ↩︎

An auction that included I Worship You, Almighty God. ↩︎

An auction that included Ever Be. ↩︎

An auction that included Forever. ↩︎

See Royalty Exchange for the latest list of auctions. Auctions for artists mentioned: TobyMac, Lecrae, Trip Lee, Kutless, Unspoken, Michael W. Smith, Micah Tyler, Sanctus Real, Tauren Wells. ↩︎

Quoted from the auction page of some Bethel Music songs. ↩︎

Quoted from this article on how businesses are trying to profit from the “faith-based” market. ↩︎

BMI used to take 10% (now raising to 15%) and Australian APRA AMCOS takes 15%, so 10-15% seems to be the standard range. CCLI does not publicly disclose how much they actually take. ↩︎

Such as Integrity Music and Emu Music. ↩︎

This exemption was part of the original Copyright Act of 1976. ↩︎

From the original report by the House Judiciary Committee in 1976. The author is explaining why the exemption specifically includes performances “that might be regarded as ‘dramatic’ in nature”, which are also exempt for “sacred” music. ↩︎

Quoted from the APRA AMCOS website. They also mention “divine services, which are exempt” in their Distribution Practices document. ↩︎

It also explicitly does not apply to “the public performance of music at functions as well as during activities such as youth groups, study groups and socials, etc.”. ↩︎

Pete Ward, Selling Worship (Paternoster, 2005), p82. ↩︎

In Australia you are covered by the current disposition of the music industry to not demand performance royalties for religious services. This situation may change at any time and there is no legal guarantee it won’t. It is also highly unlikely that many other countries have such an exemption, meaning there are probably a lot of legal gaps that are mostly ignored for the time being. ↩︎

As explained in this factsheet from them. I also wrote to CCLI regarding the situation in Australia and this was their response: “While we don’t have a religious exemption like the US, APRA AMCOS and PPCA have waived the requirement of their licence for regular worship services”. ↩︎

Quoted from this factsheet from them. ↩︎

Quoted from Title 17 section 107. ↩︎

Some music ministries did waive some rights during the pandemic. Emu Music gave permission to stream some videos but not reproductions of their songs. Sovereign Grace gave permission to stream performances of their songs but only temporarily and you still needed a church music license for the lyrics etc. ↩︎

I am not a lawyer and you’d need to carefully consider the legality of this based on your own circumstances and at your own risk. ↩︎

From The Heart Of Worship by Matt Redman, © 1997 Thankyou Music. ↩︎

As remembered by his friend, Danny Lehmann, in a documentary on Keith Green. ↩︎

Keith lived before there was much guidance available on the negative impacts of copyright and how to dedicate works to the public domain. So his songs were, unfortunately, never freed from copyright despite his good intentions. ↩︎