The Rise of the British and Foreign Bible Society

The birth of the Bible societies begins with the story of a simple girl of about 15. Many of you may have heard this before: the almost legendary account of Mary Jones. She was born in 1784 in a small, poor village in Wales. Her parents loved God, but they couldn’t afford a Bible. From the time she was little, Mary’s biggest wish was to have a Bible and read it for herself. But bibles were hard to find and cost a lot of money: about $150–$300 in today’s currency. This amount seemed an impossible obstacle for Mary, but she began saving little by little. For six long years she worked hard until she finally had enough money to buy a Bible of her own. Then she faced another challenge: the nearest place with bibles was in a town twenty-six miles away, and she had no shoes. Nevertheless, she walked all that way barefoot over rocky paths and hills until she arrived at the house of a minister who had the bibles. At first, Mary was told that they were sold out. But when the minister heard her story and saw her love for God’s Word, he was touched, and gave her a Bible. And this story of her determination and love for God’s Word encouraged others, and helped inspire the start of the British and Foreign Bible Society, which worked to make bibles available and affordable to many in Great Britain and all around the world.

Now, why were bibles so expensive and scarce at this point in time? Because of what was sometimes called the Bible Monopoly or Royal Printing Privilege, established by King James I. When the KJV was completed, special printing rights were given to only one press—The King’s Printer; and later to a couple other authorized presses. And as with all monopolies, it inevitably drove prices higher. People like John Campbell decried this monopoly as a “gigantic leech,” a “literary leviathan,” and an “abomination.”[1]

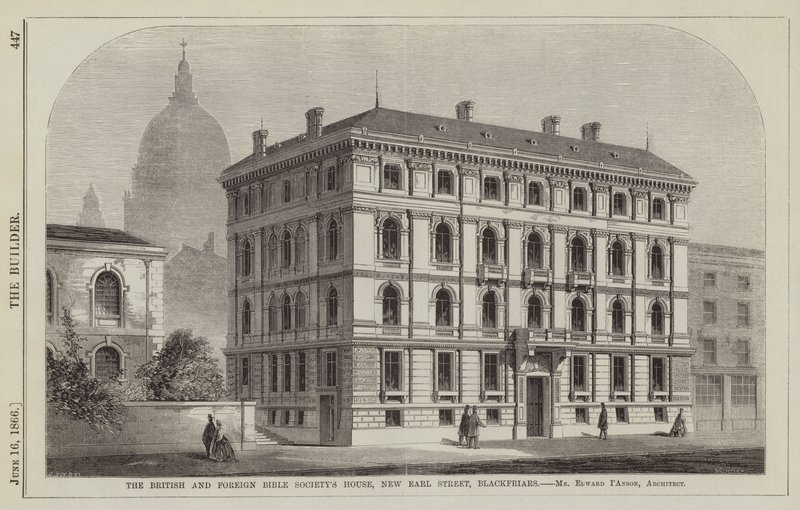

In 1804, Thomas Charles and several other concerned Christians in London, including the famous abolitionist William Wilberforce, founded the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS). Their vision was: “to translate, print and distribute the Bible … throughout the British Isles and the whole world … without any notes or commentary.” In other words, get God’s Word into people’s hands, plain and pure, with no doctrinal footnotes, and make it available to the rich and poor alike.

In the 1816 book by John Owen (not the puritan from the 17th century) on the History and Origin and First Ten Years of the British and Foreign Bible Society we read one of their founding purpose statements:

The reasons which call for such an Institution chiefly refer to the prevalence of ignorance, superstition, and idolatry over so large a portion of the world; the limited nature of the respectable Societies now in existence, and their acknowledged insufficiency to supply the demand for Bibles in the United Kingdom and Foreign Countries; and the recent attempts which have been made on the part of infidelity to discredit the evidence, vilify the character, and destroy the influence of Christianity.

The exclusive object of this Society is to diffuse the knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, by circulating them in the different languages spoken throughout Great Britain and Ireland; and also, according to the extent of its funds, by promoting the printing of them in foreign languages, and the distribution of them in foreign countries.

…In the execution of the plan, it is proposed to embrace the common support of Christians at large; and to invite the concurrence of persons of every description, who profess to regard the Scriptures as the proper Standard of Faith.[2]

Now, from this statement, can we conclude that they were establishing a ministry? According to my article on the biblical definition of Christian ministry, it is Spirit-empowered service specifically and directly for the edification of the Body of Christ. They say that their exclusive object is to “diffuse the knowledge of the Holy Scriptures.” Is that specifically and directly for the edification of the Body of Christ? I would say yes. Is it Spirit-empowered service? This is where it may be a gray area. The administration of distributing bibles doesn’t necessarily require Spirit-empowerment. Would it be valid to err on the side of calling it biblical ministry under certain conditions? I think so. But the Society did some things to ensure that the Spirit was left out as much as possible. In essence, they intentionally undermined any spiritual aspect that might accompany their mission.

But you should know that the founders of the Bible Society sometimes alluded to the idea of offering the water of life “without money and without price,” in the words of Isaiah 55:1. And they often spoke of what they were doing in biblical language as though it were a spiritual mission from heaven. Nevertheless, they did not want to be seen as a mission or ministry, but rather as a fully commercial enterprise with good intentions: to make bibles cheaper. So, from the beginning, their motivation and philosophy were full of apparent contradictions.

In her book Cheap Bibles, Leslie Howsam writes,

The ‘fundamental principle’ of distribution without note or comment was based upon the premise that the BFBS was not a religious society. As one person said, ‘It is a society for furnishing the means of religion, but not a religious society.’ This was a crucial distinction. Denominational differences made it impossible for Dissenters and Anglicans to combine together in their religious characters to distribute the scriptures. The publication of notes and comments would have raised disagreements over interpretation. So the members met as lay persons, agreeing to disagree about doctrine. It was a distinction between content and process: the scriptures themselves were religious, of course, but the process of distribution had to be a commercial one, stripped of all religious trappings, if squabbles over doctrine were to be avoided…. The tension between spiritual ends and commercial means, embedded in the constitution because of contemporary political realities, was to shape the policies of the Bible Society throughout the nineteenth century.[3]

It’s important to note that from the beginning the BFBS was not interested in giving away bibles. Their goal was only to subsidize the price of bibles through a subscription system, much like Patreon today. You would sign up for regular support, and depending on how much you gave, you would get different “perks.” Some of those came in the form of discounts, and for megadonors, it came as the privilege to vote on the board’s decisions. In 1821, a 600 page book detailing the system of the Bible society came out, explaining how things worked and why. The author gives us the reason the Society’s policy rejected the idea of simply giving bibles instead of subsidizing their cost: “In every instance gratuitous distribution should, as much as possible, be avoided; and the people be induced to purchase the Scriptures, which are generally valued and read in direct proportion to the expense or trouble which they have cost in obtaining them.” In other words, people only value what they pay for. In fact, this is the earliest expression of this mentality by a Christian that I have yet to come across. This way of thinking was already widespread in early 19th century England.

What is conspicuously absent in the documentation of the Society is thorough scriptural support for their decisions, namely the decision to charge for bibles instead of giving them away. And interestingly, when an appeal is made to the idea of partiality or favoritism found in James 2, it is applied as giving the poor equal opportunity to donate along with the rich. In other words, they had very cheap subscription tiers that even the poor could afford, so they believed they were doing well in terms of not showing partiality. Also, the verse “It is more blessed to give than to receive” is used to exhort people to give money to the Society, rather than to exhort the Society to give away bibles. Finally, Matthew 10:8 is mentioned: “freely you have received, freely give,” but their interpretation at the time seemed to be restricted to the idea of diminishing obstacles, not fully removing them. They also interpreted the command to freely give as an exhortation to give money liberally to the Society itself. So, it would seem that they believed they were obedient to this command because they were making bibles much cheaper, that is, removing the obstacle of high cost, although removing the obstacle of cost altogether was out of the question. “Freely” was understood in terms of wider access and liberality/generosity of spirit, not necessarily free of price.

Completely getting rid of the cost barrier between people and the Word was dismissed because of a folk-psychological belief not found anywhere in the Bible: the idea that people don’t value what they don’t pay for. This is, at best, a shallow generalization from certain consumer contexts, and at worst, a dangerous distortion when applied to matters of faith. Value cannot be reduced to price, empirical evidence undermines the universality of the claim, and the example of Jesus giving his life to offer salvation freely shows the folly of this misconception that has infected the Church. To predicate appreciation of Scripture on financial expenditure is to misunderstand the nature of value itself.

This lack of diligent seeking of scriptural principles by which to operate is unsurprising, considering the ecumenical nature of the Society. They were so set on being non-sectarian that preaching, sharing the gospel, or praying when representing the Bible Society were strongly discouraged. They even began including the Apocrypha in some editions to please Catholics, which resulted in no small controversy and division. Later, in 1831 another controversy erupted about Unitarians holding significant Society offices. Both of these issues resulted in some two thousand people breaking off to form the Trinitarian Bible Society.

Even so, in spite of this strict adherence to an almost secular approach in practice, people still wrote about the Society in this kind of language:

This Institution is one of the noblest monuments of Christian zeal that the world has ever beheld. It is the cause of God and of man; it is the cause of truth and of mercy; it is the cause of the everlasting Gospel. Can you hesitate to promote it? Can you remain indifferent, while thousands are perishing for lack of knowledge, and while the means of salvation are within your power to impart? ‘Freely ye have received, freely give:’ if you acknowledge for yourselves the blessed influence of divine revelation, invite others to partake of it. The light of heaven is streaming, in all its effulgence, above and around you: O, let not the beams be intercepted! Open for it a free passage into the dwellings of the poor! Be the means of conducting it into the darkest recesses of human ignorance and error! It will enter them with healing on its wings; and the wilderness shall be glad, and the desert shall rejoice and blossom as the rose.[4]

Now, there was a second reason for the policy of not giving away bibles. Howsam writes that the leaders of the Society

were no doubt influenced by contemporary concerns about the degenerating effects of charity upon the poor. To charge a small price for a cheap Bible, even to the poorest customer, would avert the danger that philanthropy might cause moral decay. It seems unlikely that working-class subscribers understood or cared about the subtle distinctions between the portion of the book they received that was paid for by voluntary donations and the part that they paid for out of their own pockets. But they almost always had to pay something. In Dudley’s opinion, which was shared by the Committee, ‘a gratuitous distribution could not satisfy the minds of those who wished to counteract the degrading influence of Pauperism, to check the progress of Infidelity, and to extend the empire of Religion and Morality.’

The Committee could not forbid its subscribers or Auxiliary leaders to make free gifts of Bibles, but such gifts were hedged around with warnings.[5]

Let’s unpack this idea of “pauperism,” “infidelity” and the general moral degradation of the poor that the Society feared as a result of giving bibles away at no cost. There was a widely shared conviction among elites, officials, and many Christians of the time that free, unconditioned giving “corrupted” the poor by taking away the driving force of necessity. It would erode work-habits and foster dependence. The term “pauperism” meant more than just poverty. It carried a bundle of moral, economic, and political connotations that are easy to miss if we read it through modern eyes.

First, “pauperism” connoted a condition of legal dependence, living off state charity rather than one’s own labor. Second, it was associated with idleness, vice, drunkenness, and sexual immorality. To be “pauperized” was to have one’s moral fiber corroded. Third, many feared the creation of a permanent dependent underclass, resentful of the wealthy. This “pauper class” was imagined as volatile, a seedbed for crime, disorder, and even political radicalism. Fourth, Christians feared that pauperism eroded humility and gratitude to God, replacing it with a spirit of entitlement and discontent. Politicians were afraid of pauperism breeding radicalism and infidelity: the dependent poor might be more open to revolutionary ideas, blaming their condition on social injustice. Fifth, it was a fiscal drain on the wealthier classes who funded relief through higher taxes levied on each parish. Landowners grumbled that they were being “taxed to support idleness.” Around £8 million/year was being spent on poor relief in England back then, which would be about a $1 billion in today’s money.

So by making even the poor pay something for bibles, the Society reassured the higher classes that their project would not foster more pauperism and create another tax-like burden on the wealthy. So if you’re trying to court the donations of the rich for your society, you want to tailor your methods to their liking; and in that era, many of the rich would not have been happy to see you giving away bibles completely free of cost.

Dudley shares an anecdote of the sort of ideal they may have had in mind: the desire for a Bible being the motivation for poor people to industriously find creative ways to earn money. He tells the story of Mary Smith, a little girl of ten years of age.

This interesting child had been long very anxious for a Bible; but her parents, who are honest but extremely poor cottagers, were unable to afford the money. Mary often brought the Collector sixpence at a time, and once brought a shilling. On being asked how she had obtained so much, it appeared that she rose every morning by five o’clock, in order to collect violets and other early spring flowers, which she made up in bunches and sold in the market. This was her own spontaneous act, suggested by her earnest desire to obtain a Bible, which will be doubly valuable as the reward of her early industry.[6]

To clarify, the meaning of the word “infidelity” (in the quote above about what the Society feared as a consequence of giving free of cost) had to do with religion and politics. It was the fear of the spread of unbelief, deism, and radical politics among the poor. They believed that if they just gave bibles away for nothing, the poor might take the Bible lightly, ignore it, or fall prey to “infidel” ideas.

And there was also a third reason the Society avoided giving bibles as gifts. Howsam writes that it was “the possibility that generosity might be exploited by the unscrupulous. There was a constant risk that poor people might pawn their Bibles.”[7]

It is here that we begin to see a common thread: letting fear (not faith) drive practice.

Nevertheless, God has used this initiative tremendously. Hundreds of millions of people have gotten access to Scripture through the Society’s efforts all around the world. Even during the world wars they were untiring in their devotion to getting bibles into the hands of soldiers and prisoners in hard-to-reach, risky places. In WWI alone they distributed more than nine million copies of Scripture, in over 80 languages. And they have been instrumental in translating the Bible into many languages.

The Rise of the American Bible Society

In America, Bible societies began to spring up in the early 1800s. The hope of building a Protestant republic by flooding the nation with Scripture drove many of these societies. In his book The Bible Cause, John Fea describes their way of thinking:

If everyone had access to a Bible, “prejudice” and “narrowness of education” would be overwhelmed by a patriotic and unified spirit of self-sacrifice. The word of God was the only way for the nation to heal itself of the wounds it had suffered from decades of self-interested factionalism.[8]

Other leaders in the movement believed that they were ushering in a new era of moral improvement for the world, and that the mass distribution of Scripture would usher in the Second Coming. It’s also important to understand that the emergence of these societies went hand-in-hand with the Second Great Awakening. And their work often served as a catalyst for local revivals.[9]

In contrast to the BFBS, early American Bible societies sought to give bibles away for free. In those first decades, charity was their identity. In the words of one historian, “Their business was benevolence, not bookselling.”[10] The Americans were more likely to see themselves first and foremost as ministries. The foundational writings are full of the language of freely giving, using Isaiah 55 as a guiding principle: “without money and without price.” While the BFBS stressed payment and moral discipline, the American Bible societies stressed charity and grace. In my research I could not find any explicit reason for this difference, nor any writings from the Americans that criticize the approach of the BFBS.

By 1816, over 130 local Bible societies had formed in the U.S. These local societies, often organized by churches in various cities and states, shared the conviction that no one should be denied a Bible because of cost. They described their goal as distributing the Bible “among persons who are unable or not disposed to purchase it.” For those who could afford to pay even a little, the societies would offer bibles at a very low price: sometimes just the cost of printing, sometimes even less, subsidized by donations.

To coordinate this growing movement, leaders felt a need for a national organization. In May 1816, delegates from 28 of these local societies met in New York City and founded the American Bible Society (ABS), which “would become one of the largest and most influential Christian organizations in American history.”[11] From the start, the American Bible Society echoed the ecumenical principle of the British society: to distribute Scripture “without note or comment.”

As a parentheses on their strict adherence to their non-denominational policy, let me share an example. In 1835, the British Baptist Mission in Calcutta, India, appealed to the ABS for help in funding a translation of the New Testament into Bengali. The ABS refused to fund the project because the translators of the Bengali Bible translated baptizo (the Greek word for “baptism”) in a way that communicated the Baptist practice of immersion, as opposed to sprinkling. They reminded the British Baptist Mission that they were not interested in promoting “local feelings, party prejudices” and “sectarian jealousies.”[12] And throughout much of its history, the ABS measured success not in terms of conversions or changed lives, but in terms of the amount of bibles distributed around the world each year.

In the early 1800s, printing was undergoing a revolution. Traditional printing with movable type was labor-intensive and expensive. But a new method called stereotype printing emerged, and the Bible societies eagerly embraced it. Basically, this new technology involved creating a permanent metal plate for each page of a book. Using a mold, printers would cast a whole page of type in one piece of metal. This plate could then be used to print thousands of copies without needing to reset any type. The upfront cost of making the plates was high, but once you had them, each additional copy was cheap and easy to print. It also ensured consistency and fewer typos across all copies.

The American Bible Society and its auxiliaries became pioneers in this technology, and invested heavily in printing infrastructure. By the 1820s, the ABS and its auxiliaries were producing Bibles on a scale previously unimaginable. And because of the efficiencies of stereotyping, the cost per Bible decreased over time. But this required a large amount of capital upfront to fund. Their sense of urgency and ambition drove them to make a fateful decision: get more money to print more bibles by becoming a commercial enterprise. In other words, more money, more ministry. So, money had to be obtained—whether that be through sales or donations. And like the BFBS, this decision was not made based on scriptural principle but rather expedience, pragmatism, and economic logic. The leadership of the ABS wrote, “The Managers deem it expedient to renew their recommendation to the Auxiliaries to sell the Scriptures at cost or at reduced prices, in preference to distributing them gratuitously.”[13]

The societies developed a form of differential pricing. There were premium editions for the trade, cost-covering prices for general buyers, subsidized rates for auxiliaries, and free copies for the indigent.[14] By the end of the 1820s, the ABS had become one of the largest publishing houses in the country, nearly holding a monopoly over the production of inexpensive bibles in the U.S.[15] They, along with the American Tract Society and the American Sunday School Union had become national publishing corporations, indistinguishable in business methods from secular enterprises.[16]

Critics began to accuse them of hypocrisy. One insider wrote An Exposé of the Rise and Proceedings of the American Bible Society, arguing that selling Scripture “mocked the claim of publishers to furnish Scripture ‘without money and without price’”[17] (Isa 55:1). He pointed out that the societies had accumulated vast wealth in stereotype plates, real estate, and buildings, enriching themselves while claiming to serve the poor. The author wrote:

The community had zealously assisted their spiritual teachers in the formation of this Society, on the supposition that it would dispense their charities collectively, to those who needed them, to much better advantage than they themselves could do individually. But in this the public were to be deceived. The benefit of the suffering community–suffering for the want of spiritual food, was of very minor consideration when compared with “the best interests of this Society.” Contributions and donations were pouring in from every section of this vast republic, for the purpose of gratuitously furnishing the destitute with that which the benevolent said they most needed, viz. the Bible, when the Managers very gravely passed the following “Resolution,” which they unblushingly promulgated.

“Resolved, That in ordinary cases occurring within the United States, it is inconsistent with the best interests of this Society to distribute the Bible gratuitously, except through the medium of Auxiliary Societies.”[18]

He then explains: “At a cursory view of this ‘Resolution,’ it may appear to some that this institution still furnishes the Scriptures gratuitously, though it may be through the medium of Auxiliary Societies. But such is not the fact.”[19] Furthermore, he predicted that this new commercial approach would eliminate all competition.

Other critics shared this concern about the impact on commercial publishers. By using charitable donations to subsidize low-cost Bibles, the societies were distorting the market and crowding out honest competition. A guy named Herman Hooker wrote a booklet titled An Appeal to the Christian Public, on the Evil and Impolicy of the Church Engaging in Merchandise, in which he said, “What business have Christians to give their charity to do that which business enterprise and capital would do, if let alone, quite as well and cheaply?”[20]

Even within the societies, some leaders came to recognize the problem. They admitted that under the sales model, Scripture flowed primarily to those with money and undermined the charitable nature of their mission. Nord writes, “Ironically, the turn to retail sales, which was designed to produce universal circulation, not profit, had entrapped the societies in market forces they had been founded to resist.”[21]

A periodical called The Reformer also consistently attacked the ABS. It was run by men who were zealously opposed to both Calvinism and what we would call parachurch organizations today. “Its readers included…men and women who felt that their liberty was threatened by the attempts of benevolent societies to exert ecclesiastical and cultural power over America through the establishment of a Christian nation…. Its authors challenged the notion that Christianity—particularly Presbyterianism—must become the official religion of the nation.”[22]

John Fea writes,

The editors of The Reformer argued that the ABS reports on the Bible needs of the United States were heavily exaggerated. Gates [one of the lead editors] questioned ABS assertions that there were “whole neighborhoods in which there was not a single copy of the Bible.” He found this hard to believe, since, as he put it, “almost every storekeeper in the country keeps Bibles to dispose of, and no one that valued the Bible more than all his property would long be without one.” According to Gates, such reports were published to convince unsuspecting Christians to donate more money to the ABS, which, in turn, would empower them further to infiltrate the government and establish a Presbyterian nation.[23]

Copyright and Proprietary Control

Amid this growing entanglement with market mechanisms, the question of intellectual property arose. Early Bible societies operated in a legal gray zone. The text of the King James Bible, their main version, was not protected by American copyright law, even though it remained under the perpetual copyright of the Crown in the United Kingdom. This empowered any American to print the text of Scripture—a luxury the British did not have. But the publishing of copyright-free bibles would soon go the way of all flesh.

The Revised Version (RV or ERV, 1885) led to the advent of the first copyrighted Bible in the U.S. Published initially by the British, the RV was the first major revision since the 1769 Blayney revision of the 1611 King James. It took a long time to convince the right authorities in England that such a revision was possible and desirable, and that it wouldn’t ruin the revered and loved KJV. Once enough people were persuaded, the Oxford and Cambridge presses funded the revision, spending what would be millions of dollars in today’s money over the course of 12 years to pay the team of scholars who worked on it. Oxford and Cambridge were guaranteed the same monopoly on printing and selling the new version, so it was a small investment in comparison to the profits they would earn when it was released. It was suggested that they invite input from American scholars on their work, and everyone was in agreement that it was a good idea. So, under the direction of Philip Schaff, two American committees were formed in 1871—one for each testament. Members were drawn from multiple denominations and included eminent scholars. The Americans followed the same rules as the English, but their role was advisory. Drafts produced in England were sent to them, they reviewed and annotated them, and their suggestions were considered in subsequent revisions. Although they had no decisive vote, their influence was real, and a record of the preferences the British decided not to follow was eventually published as an appendix in American editions.

Philip Schaff highlighted the cooperative spirit across the Atlantic, noting that the project symbolized unity of faith among English-speaking Protestants. The Americans financed their own work through voluntary donations. You can read about the detailed process, including how the project was funded and who the donors were, in the public domain book A Historical Account of the Work of the American Committee of Revision of the Authorized English Version of the Bible. The British project did not help fund the American’s work, and all of the American scholars worked as a labor of love and received no salary from the project funds. The voluntary donations that supported the project instead served to cover travel, clerical help, office space, printing, and books. By the end of the 12-year project, the total amount donated was $47,561, and, after expenses, they were left with a balance of a little over $9,000 for further expenses and gift copies for donors. Today, that figure would be around $1,400,000. So their operating costs came out to be about $120,000 per year (in present day [2025] dollars).

When the New Testament came out, it was a hit. In May 1881, the Chicago Tribune printed it in its entirety in a single Sunday newspaper, and sold 107,000 copies.[24] The Tribune freely used the biblical text from the British publishers, since at the time, no international agreement had been made to enforce copyright laws across national borders.[25] Rival papers did likewise. American book publishers also sold bound copies, and over a million copies of the RV sold within months. This frenzy highlighted the possible profits that might be gained by copyrighting the text in America to ensure a monopoly on sales. American publishers were paying attention. The stage was set for a shift in the stance of Bible publishers towards copyright.

Although American churches had enjoyed the British revision, they still wanted their own edition with American-preferred renderings in the body of the text. But, as already mentioned, there was a gentlemen’s agreement between the British and American committee that the Americans would refrain from publishing such an edition until fourteen years had passed. In the meanwhile they would need to settle for an appendix in American editions that informed readers as to what those American preferences were. To name a few examples, the American Committee wanted:

- Jehovah instead of LORD,

- Holy Spirit instead of Holy Ghost,

- demons instead of devils, and

- covenant instead of testament.[26]

This agreement, however, could not be enforced by law in America. There were publishers who took the notes in the appendix, incorporated those changes into the body of the text before the waiting period had expired, and made some money. And one of the most reputable Christian publishing houses in the nation watched this happen. This was Thomas Nelson & Sons.

Thomas Nelson started his business in Scotland, and by the mid-19th century opened a branch in New York. They specialized in high-quality bibles, prayer-books, and hymnals, especially those coming out of Oxford University Press. In other words, they were the primary distributor of Oxford bibles in America. This made them a natural partner for the American Revision Committee. Nelson had the infrastructure to print premium bibles and an established distribution network among churches and booksellers. And they had already published the British Revised Version in 1885 for the U.S. market.

So you can imagine that, after seeing the potential profits for an official American Revised Version, and after seeing how things played out with other presses printing their own editions contrary to the wishes of the British and American committees, and seeing the way Oxford and Cambridge University presses grew rich from their printing monopoly in England through the perpetual copyright of the Crown—Thomas Nelson wanted to make the deal as sweet for themselves as possible.

They ended up getting the contract, and the American Standard Version (ASV) was published in 1901. And it included a copyright notice. Why? It would seem that Thomas Nelson anticipated questions, so a nebulous reason was given: “to insure purity of text.” Later, it was explained that:

Because of unhappy experience with unauthorized publications in the two decades between 1881 and 1901, which tampered with the text of the English Revised Version in the supposed interest of the American public [by placing the American preferences into the main text rather than in the appendix], the American Standard Version was copyrighted, to protect the text from unauthorized changes.[27]

Let’s unpack this. The “unhappy experience” that motivated this change was simply the faithful adaptation of the text to the American preferences. This change was “unauthorized,” but it didn’t introduce errors or heretical readings into the text. So, it can be concluded that the clause “to ensure purity of text” in the ASV was disingenuous. There were no reports of someone trying to commandeer the text for malicious purposes, or hostile parties corrupting the text in order to deceive readers, or cult leaders appropriating it for their own heretical ends. Instead, a petty pretense laid the foundation for a new tradition of binding the Word of God with the traditions of men.

Another angle of this you have to understand is that, because of the nature of printing back then, typos were bound to be introduced by the typesetters of presses that were less careful or meticulous. This is obviously no longer a problem today with the way we can make perfect digital copies of a work. A typo-free Bible is a completely different kind of purity of text than a heresy-free Bible. It may be that there was a concern for minimizing typos, and they believed that such a thing could be accomplished by monopolizing and centralizing the printing permission. But they should have known that ever since the KJV came out, the centralized printing monopoly for that version in Great Britain had been plagued by numerous typos in its editions. An entire book was published about this problem in 1833 by Thomas Curtis, showing that the monopoly on printing the KJV was making the the Oxford and Cambridge presses lazy, and they were producing texts of poor quality and accuracy. This is a basic principle proven over and over throughout history: monopoly ultimately leads to lower quality and higher prices for everyone.

But in the end, was purity of text really the reason? No publisher is going to print on the cover page of a Bible that it was copyrighted because they wanted more money. But the fact is that the copyright provided an immense economic reward for the publisher.

So how did Thomas Nelson get the American Committee to agree to the addition of a copyright notice? Here’s what led up to it. The American Committee decided to work on many more changes in addition to what they had already suggested to the British. They did this in anticipation of the date when they would be free to publish a fully revised American edition. But they ran out of money for this extra work. Thomas Nelson gave them $25,000 dollars (about $1 million today) to cover the costs. And this was essentially repaid by granting Nelson exclusive publishing rights.

So what did the American Committee think of the copyright issue?

First of all, ironically, they praised the fact that the 14 year agreement they had with the British “freed the book from all restrictions from copyright in this country, and made it a gift to the people.”[28] Commenting further on the issue of copyright, they wrote:

It was at no time desired by the American Committee to have any such arrangement made between themselves and publishers in the United States, or in any way to put a restriction on the sale of the new book, for the purpose of securing any remuneration for their own services or any benefit for themselves whatever. No copyright was thought of or wished for in this country with any such end in view. At one time, however, the subject of securing a copyright here for the solo [sic] purpose of preventing the publication of inaccurate and imperfect editions, was considered and discussed. This led to a series of communications with the managers of the University Presses, and also to some inquiries addressed to legal authorities in the United States. The feeling, however, on the part of the members of the American Committee was so general and so permanent, that the book should be made a free gift to the public, with no limitation whatever in the way of its widest circulation, that the whole matter was laid aside by common consent.… The determination of the American gentlemen was that they would not receive pecuniary benefit [relating to or involving money] from their work, or even, in any way, seem to do so; and, after due consideration, it was thought that the danger of the appearance of undesirable editions was not sufficient to lead them to reverse or turn aside from their settled purpose. As some standard edition, however, was necessary, the American Committee agreed to make a public statement, that the one issued by the University Presses was the one for whose accuracy they would hold themselves responsible.[29]

This was published in 1885. But things were about to change in the years that ensued between the publication of the RV and the ASV. Matthew Riddle recorded what happened in his 1905 book The Story of the Revised New Testament, American Standard Edition. After the death of Philip Schaff in 1893, the American Committee lost both its chief leader and its most effective fundraiser, making it very difficult to raise the money needed for the final revision and preparation of the text for publication in 1901. By 1895 only three members of the New Testament Company were still alive, and though determined to continue, they knew they could not cover the costs of the final preparation of the text for publication themselves. At that point in time few publishers would risk printing the work without copyright protection.

In 1897, Thomas Nelson and Sons stepped in and agreed to finance the work in return for the copyright. They even offered personal salaries to the surviving revisers, but Professor Thayer rejected the idea, insisting he could never accept money for Bible revision. As a result, the scholars completed their heavy labor without pay, while Thomas Nelson gave $25,000 to cover expenses.

So you can imagine a few men at the end of their lives, tired, and just wanting to see their life’s work finally get published. They’ve run out of options, perhaps are desperate, and Thomas Nelson sees a multimillion dollar opportunity easy for the taking. There was no doubt in the mind of any publisher, based on the past sales of the RV, that printing the ASV was a risk-free way to make a killing, with or without copyright protection. But copyright protection ensured an even greater fortune from this guaranteed best-seller. The few remaining men from the committee probably ran out of energy to insist on their copyright-free philosophy expressed back in 1885. Compromise must have seemed inevitable.

The only thing that remained was for Thomas Nelson to whitewash the cash-grab with a plausible, pious-sounding rationale: safeguarding the purity of the text. And this conveniently aligned with securing a printing monopoly.[30]

What Went Wrong

Let’s unpack what went wrong and how this might have been avoided. First, what were the mistakes of the American revisers?

- They failed to operate on biblical principle when deciding what to do about copyright, even when they arrived at the conviction that it was not desired. And when fatigue buffeted them and expedience came calling, they didn’t have the ballast to remain firm in their conviction. Their lack of theological grounding in the area of money and ministry left them vulnerable to compromise.

- They failed to persevere in reliance on God to provide through his people’s voluntary giving. Although they knew that the project had already raised the equivalent of over a million dollars in today’s money, they felt that it would be easier to “sell their birthright” for the money to get the job done. Being reticent to depend on God through his people’s generosity is common in many people. Just like Peter on the water, fear often grips us, our faith falters, and we begin to sink into the world’s wisdom.

- They let the tyranny of urgency prevail. It’s understandable that they wanted their life’s work to get into people’s hands sooner than later, but our timeline is not always God’s. Having patience for his provision is hard, but obedience is worth the wait. And the fruit of a free text is inestimable.

- They trusted a publisher more than the Church. They appealed to the marketplace to do what the Body of Christ was meant to do.

Second, what were some of the faults of Thomas Nelson & Sons?

- As a Christian publisher, they failed to care about the greater impact a copyright-free Bible would have for the Kingdom of God. They knew that if they were the sole publisher it would create a bottleneck on accessibility, and fewer people would ultimately get access to a Bible in language they understand better than the archaic British English. But they didn’t care.

- They failed to consider (or ignored) the implications of copyrighting the Word of God, which ended up shifting the relationship of Christians to the Bible from one of stewardship to ownership. Not only that, but they single-handedly paved the way for all future Bible versions to be copyrighted in the United States.

Finally, where did the Church fail?

- American churches should have rallied to the cause when the Committee’s funds ran low if this version was something they truly wanted. Had they known the consequences of Bible copyright, they likely would have given joyfully and sacrificially to keep the text free.

- They abdicated their responsibility before God to steward the Word and left everything to the publishers, even when it meant loss of access.

- Like many Christians in Nazi Germany remained silent in the face of compromise, there was little outcry about the copyright decision. They failed to question and resist the binding of the Spirit’s work with the laws of men.

Dr. Maurice Robinson in his article The Bondage of the Word writes:

Somewhere a great evil is involved whenever the people of God permit commercial publishers to hold hostage their sacred texts by copyright and licensing restrictions; for far too long the Christian community has been distracted from seeing the full implications of this matter, and the time is rapidly approaching when it may be too late to take reconstructive action.[31]

By the late 20th century it was not uncommon to hear critics claiming that new Bible versions were merely “made for money,” often praising the KJV as superior because it could be freely reproduced. The view that modern translations are driven by greed is still alive and well.[32] These accusations of profit motive and restrictive access have plagued new Bible releases. What this shows is that even fellow believers struggle to see pure motives behind new Bible translations or revisions. Imagine what the watching unbelieving world thinks. Whatever the truth may be, and no matter how many sincere, wonderful, genuine followers of Christ are involved in the publication of these versions, the optics are not good.

Defenders of the practice have countered that translation projects cost millions, and without copyright, few publishers could afford such work. But many ministries bring in tens of millions of dollars in donations every year—which clearly means that Bible publishers could fund even the most expensive revision work through support instead of sales. They simply choose not to.

And the proliferation of versions, each with its own copyright, has reinforced the notion that intellectual property is and should be a normal part of Bible publishing. The default assumption is: if it’s a modern Bible, somebody owns it, and that somebody isn’t God.

It’s important to acknowledge that Biblica (previously known as the International Bible Society) has embraced open licenses for many of its Bible versions in different languages. However, it has not chosen to release them to the public domain. Otherwise, Bible societies around the world have taken up this dark mantle of uncritically espousing the trend of copyrighting biblical texts. What began as a mission to give the Bible away evolved into a business model that required restricting others from freely doing so. And as Bible publishers became awash in a sea of commercialism, the question of “What will sell?” eclipsed all other priorities.

The challenge for the 21st-century church is to recover the original vision of the Apostle Paul: that the Word of the Lord “run freely and be glorified” (2 Thess 3:1). Or as John Campbell put it back in 1840, “let us rejoice if the storm of public opinion is breaking down a barrier which interrupts the full tide of the water of life, and is making a wider channel, that ‘the word of the Lord may have free course, run, and be glorified.’”[33]

Appendix: Matthew Riddle’s Account of the Agreement with Thomas Nelson & Sons

The method of publication caused some perplexity. The expenses of the American Companies during the period of co-operation had been met by private subscription, and the additional outlay in the preparation of the American Revised Version might have been provided in the same way. But this plan would have left the edition unprotected by copyright, and would have opened the way for unauthorized and incorrect issues, as in 1881. Still the Committee would have preferred this method, could the necessary funds have been provided. At the same time it was evident that few publishing houses would undertake the publication unless protected by copyright.

As the years passed, death removed many of the New Testament Company; most of the survivors were burdened with years or with exacting duties. It seemed increasingly difficult for them to undertake the responsibility of publishing as well as preparing the proposed American Revised Version. As Dr. Schaff had been so successful in soliciting funds for the expenses prior to 1881, both companies instinctively looked to him for leadership in the new enterprise. He maintained his interest to the last, attending a meeting of the New Testament Company, at New Haven, in June, 1893, only four months before his lamented death, October 20 of that year. He made some suggestions at this meeting which were followed in the preparation of the new edition. But the loss of this leader was a great discouragement to the few surviving members of the committee. Professor Thayer, the secretary of the New Testament Company, under date of August 19, 1895, wrote to Dr. David S. Schaff (Life of Philip Schaff, p. 387): “With your father’s death the prospect of success in the solicitation of funds disappeared, and our diminishing numbers and taxed leisure have held the whole project in suspense to this hour.”

There was, however, no thought of abandoning the project. At the date of Professor Thayer’s letter only three members of the New Testament Company survived: Drs. Dwight, Thayer and Riddle, and these three edited the American Standard edition of the New Testament. It was felt by all of them that it would be necessary to secure a responsible publishing firm that would provide the necessary expenses of preparation, and in return be granted the copyright. Finally (and fortunately it has proved) Messrs. Thomas Nelson and Sons entered into negotiations with the Committee. In April, 1897, a meeting was held at the Bible House, New York, to confer with the New York representative of this publishing firm. Several details were fully discussed. It was decided, at the desire of the Messrs. Nelson, that a new and complete set of references be prepared. The size of the volume, the arrangement of marginal readings and renderings, and of Old Testament citations, were virtually agreed upon. At this conference the publishers expressed their willingness, not only to defray the necessary expenses of the Revisers, incident to the preparation of the volume, but also to make some pecuniary compensation to the surviving members. When this proposal was made, Professor Thayer, whose duties in preparing the Revised New Testament were likely to be most onerous, at once replied: “If I took money for this work, I would be ashamed to meet President Woolsey in Heaven!” The arduous labors that followed, probably the most exacting in the entire history of the Revision, were performed gratuitously.[34]

John Campbell, Monopoly and Unrestricted Circulation of the Sacred Scriptures Contrasted (London: Seeleys, 1840), 96. ↩︎

John Owen, The History and Origin and First Ten Years of the British and Foreign Bible Society (London: Tilling and Hughes, 1816), 65. ↩︎

Leslie Howsam, Cheap Bibles: Nineteenth-Century Publishing and the British and Foreign Bible Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 6-7. ↩︎

John Dudley, An Analysis of the System of the Bible Society: Throughout Its Various Parts, Including a Sketch of the Origin and Results of Auxiliary and Branch Societies, and Bible Associations, in England, Ireland, Scotland, and America (London: J. Hatchard and Son, 1825), 65. ↩︎

Howsam, Cheap Bibles, 50. ↩︎

John Dudley, An Analysis of the System of the Bible Society, 286. ↩︎

Howsam, Cheap Bibles, 66. ↩︎

John Fea, The Bible Cause: A History of the American Bible Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 23. ↩︎

Ibid., 52. ↩︎

David Paul Nord, “Free Grace, Free Books, Free Riders: The Economics of Religious Publishing in Early Nineteenth-Century America,” in Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 107, no. 2 (1997): 270–72. ↩︎

Ibid., 29. ↩︎

Ibid., 65. ↩︎

American Bible Society, Seventh Annual Report (1823), 24. ↩︎

“Essentially, they had four prices: 1) a premium price for trade Bibles on fine paper; 2) a price modestly above cost for regular Bibles sold to outsiders; 3) a ‘first cost’ price for Bibles sold to other societies and auxiliaries; and 4) a zero price for Bibles given to destitute persons, through the Philadelphia headquarters directly or through the little societies.” Ibid., 254. ↩︎

Nord, “Free Grace,” 256. ↩︎

David Paul Nord, “Benevolent Capital: Financing Evangelical Book Publishing in Early Nineteenth‑Century America,” in God and Mammon: Protestants, Money, and the Market, 1790‑1860, ed. Mark A. Noll (New York / Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 157-160. ↩︎

Exposé, 13–14. ↩︎

Ibid., 8-9. ↩︎

Ibid., 10. ↩︎

Herman Hooker, An Appeal to the Christian Public, on the Evil and Impolicy of the Church Engaging in Merchandise (Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1849), 5-6. ↩︎

Nord, “Benevolent Capital,” 160. ↩︎

Fea, The Bible Cause, 60. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ibid., 78. ↩︎

The Berne Convention would not take place until 1886 to establish international copyright law. ↩︎

See the 1885 ERV appendix for the full list of American preferences: https://archive.org/details/holybiblecontain00unse_44/page/n1745/mode/2up. See also the preface to the ASV. ↩︎

The New Covenant, Commonly called the New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Revised Standard Version (New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1946), “Preface,” iii-iv. ↩︎

Historical Account, 55. ↩︎

American Committee of Revision of the Authorized English Version of the Bible, Historical Account of the Work of the American Committee of Revision of the Authorized English Version of the Bible: Prepared from the Documents and Correspondence of the Committee (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885), 50-51. Emphasis added. ↩︎

At that time in the United States, copyright law (under the 1870 Copyright Act) gave an initial term of 28 years. It was renewed for another 28 years by the International Council of Religious Education (it entered the public domain in 1957). ↩︎

Maurice A. Robinson, The Bondage of the Word: Copyright and the Bible (1996), accessed May 20, 2025, https://sellingjesus.org/articles/copyright-and-the-bible. ↩︎

Doug Kutilek, The KJV Is a Copyrighted Translation, accessed May 20, 2025. https://www.beacon-ministries.org/?subpages/The-KJV--is-a-Copyrighted-Version.shtml#:~:text=One very bizarre reason for,as one recent publication stated. ↩︎

Campbell, Monopoly and Unrestricted Circulation of the Sacred Scriptures Contrasted, 101. ↩︎

Matthew Brown Riddle, The Story of the Revised New Testament, American Standard Edition (New York: Thomas Whittaker, 1908). ↩︎